Oren Abeles, Michigan Technological University[1]

After the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting, there were widespread calls to prohibit a firearms accessory called a “bump stock.” The shooter equipped his rifles with these devices, which simulate fully-automatic fire (multiple shots with a single trigger pull) in semi-automatic rifles (shooting only one bullet for each trigger pull). In a rare political consensus, even the National Rifle Association called for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) to consider regulation. What was not widely mentioned, however, was that ATF had previously ruled that bump stocks were machine gun parts and, thus, governable by the same prohibitions regulating fully-automatic weapons (Vazquez 2-3). ATF even ordered the bump stock’s inventor, Bill Akins, to surrender his inventory (3).

How, then, did redesigned bump stocks reappear, unregulated and available to anyone with $99? What might seem like a separate question also presses: was this technology to blame for the Las Vegas shooting? This essay offers a way to answer both questions because they are, I want to argue, inextricably linked. As we shall see, the bump stock’s redesign was possible because its manufacturer argued that the technology had no agency of its own. At the same time, however, the rhetorical tropes articulating redesigned bump stocks show they are inseparable from the agency of human users. And I want to explore something further, whether the material relationship between humans and this technology can itself be understood tropologically, as a rhetorical involvement that “turns” (the literal translation of trope) users and instruments toward one another as it “turns” them toward new agencies. Such turning would afford capacities neither user nor technology has separately. This essay, then, attempts to further discern a rhetoricity assembling humans and technology, an emergence we can trace tropologically.

I am not the first to argue for technological rhetoricity or how such rhetoricity elaborates thing-oriented ontology (Brown and Rivers 215; Cooper 20-29; Graham 119-121; Rickert 205-207; Pflugfelder 118-121). Much of this scholarship is inspired by Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network-Theory (ANT) and for studying firearms technologies, Latour’s ANT might be perfect, as guns and users are one of Latour’s examples of posthuman ontology. As Latour describes, it is neither guns that kill people nor people that kill people but an emergent agency gathering the two together (Pandora’s 176-178). Thomas Rickert (Ambient 205-206), Ehren Pflugfelder (121), and Paul Lynch and Nathaniel Rivers (6) all argue rhetoric can learn from this parable, discerning a diffuse rhetoricity persuading actors to assemble.

So, tracing the bump stock’s rhetoricity might seem simple. Latour provides the philosophy, just as a number of theorists show how persuasion can trace thing-oriented assembly. Yet such efforts have been complicated and made so by Latour himself. In a 2017 interview by Lynda Walsh, Latour asserted rhetoric was not capable of tracing ontology or nonhumans (“Interview” 404, 415-416). He does prize rhetoric’s willingness to engage in disputable proofs and its persuasive utility amidst contingent events. In contrast to Platonic ideality or Cartesian certainty, Latour favors persuasive deliberations open to emergent concerns, using facts produced within those same suasive processes (“Interview” 415-416; “From Realpolitik” 9, 16). For Latour, assemblies are fundamentally surprising—they are events irreducible to antecedents—and thus require equally responsive suasive discourses (Politics 78-80, 146-148). Yet Latour makes a distinction between rhetoric’s openness to indeterminacy and the ontological dynamics that produce assembly amidst indeterminacy. He thinks rhetoric vital for speaking persuasively about contingent becomings, but he doesn’t think becoming is suasive.

None of this prevents retheorizing Latour’s work to discern thing-oriented rhetoricity. Such retheorization is a hallmark of Latour’s rhetorical interpreters, who often deploy the dynamics of persuasion to describe effects nonhumans have on humans and vice versa (Prenosil 98, 108; Rivers 427; Lynch and Rivers 4-5; Bay 440; Pflugfelder 125; Rickert, Ambient 136; Muckelbauer 36). This can be productive, as nonhumans clearly have suasive effects. But as Thomas Rickert points out, seeing ANT as just a study of persuasion may limit it to tracing suasive influence, leaving the original becoming of suasive nonhumans unexplained and ultimately putting the agential onus back on humans for determining how nonhumans assemble (Ambient 267; “The Whole” 148). Nathan Stormer makes a similar point, arguing that tracing just persuasion implies 1) a persuading subject and 2) separate things that change from suasive influence (259-260). By contrast, Latourian ontology asserts that assembling events precede and constitute subjects and objects through relations. Theorizing assembly as linear suasive influence can make it difficult to retrieve some of the very aspects of Latour’s philosophy (flat ontology, relations preceding relata, emergent assemblages) that attracted rhetorical scholarship.

Yet just as there is no need to confine ANT to Latour’s limited rhetorical theory, there is also no reason to confine a rhetorical theory of ANT to persuasion’s limiting dynamics. Indeed, it would be ironic if incorporating ANT to rethink rhetoric’s limits ended up extending its traditional limit, persuasion, to include more (nonhuman) entities. This essay attempts to discern Latourian rhetoricity beyond persuasion. It does so not to police rhetorical interpretations of Latour, but to demonstrate that studying ANT beyond persuasion helps foreground aspects of Latour’s philosophy that productively intersect with central concerns of contemporary rhetorical theory. In particular, the essay shows how reinterpreting Latour’s work makes a profitable contribution to rhetorical notions of performativity, contingency, articulation, and trope, especially in the service of discerning posthuman rhetoricity.

What I offer below, then, is a twofold argument for a revised rhetoric of ANT, departing from Latour’s conception of rhetoric as open-ended persuasive politics and a rhetorical conception of ANT as thing-oriented persuasion. I begin by retooling Latourian rhetoricity around the concept of tropological articulation. That both Latour and rhetoric share commitments to articulation has been noted (Prenosil 98; Greene) but not frequently. Neither has their similar commitment to trope’s formal dynamics, particularly the dynamics of metaphor and metonymy. Thus, before this essay traces the bump stock’s reemergence, its first half theorizes a closer calibration of Latourian and rhetorical concepts of articulation and trope, as well complementary issues of performativity and contingency.

Both ANT and ANT-inspired rhetorical theory benefit from rethinking their commitments in these terms. For ANT, studying tropological dynamics adds specificity to Latourian articulation, particularly the way contingent assemblies emerge amidst indeterminacy. This is a continuing theme of Latour’s corpus, yet his work doesn’t develop a theoretical language capable of exploring ontological indeterminacy in the same register that characterizes articulated, determinate structure. As described below, tracing metaphor and metonymy can help do that.[1]

Analogously, this essay further develops rhetorical accounts of ANT and Latourian articulation. Good work has been done on this, including clarifying discussions of how contingent posthuman articulations lend themselves to rhetorical analysis (e.g. Greene; Rickert “The Whole”; Cooper). Yet there is a need to make clear what Latour’s version of articulation offers rhetorical theory that other rhetorical dynamics, namely persuasion, do not. I demonstrate this by reinterpreting one of Latour’s own case studies of technological articulation, showing how it allows us to align tropological rhetoricity and ANT. I then provide a similar analysis of the bump stock-human assemblage, showing how we can account for that actor-network’s emergence as tropological articulation.

In all these efforts, my goal is not to provide a complete rhetorical ontology. That would require much more space than I have here, and more resources than just Latour or tropological theory. In particular, I do not now address important questions of how human-technological contexts are themselves assembled within broader social assemblages (as in the deeply significant relationships between firearms technology, gun culture, and systemic violence). The purpose of this provisionally contracted scope is not to ignore sociopolitical context but to expand our conception of the actants assembling such context and their processes of assembly. It is a tactical analysis in keeping with Latour’s own method, which responds to earlier scholarship that either reduced scientific and technological assemblages to an effect of traditional social agencies or maintained a traditional Enlightenment separation between technoscience and society (Pandora’s Hope 27; 109-112; 164-165; The Pasteurization 140). Latour’s goal (and mine) is not to ignore these traditional social agencies but to show how ANT helps us rethink what we mean by “social” and “agency.”

Such focus does not perforce require a wholesale dismissal of more overtly political scholarship or the analysis of a wider political context. Instead, reassembling the social to include nonhumans can lead to more incisive and well-rounded explications of sociopolitical phenomena, including hegemony, racism, and violent affective regimes. Consider Latour’s seemingly microscale and constrained focus in The Pasteurization of France. The aim of that work was not to confine politics to the esoteric posthuman practices of Pasteurian technoscience. Instead, part of Latour’s goal was to elucidate how Pasteur’s microscale culture of biopolitical control was eventually rearticulated through a macroscale culture of colonial and class oppression (The Pasteurization 140-145).

Other extensions of assemblage theory, posthumanism, and object-oriented thinking can develop equally useful political critiques. Lauren Wilcox, for instance, has studied how military drone aircraft and the algorithmic ensembles surrounding them afford the circulation of racist and sexist affective regimes. Contrary to notions of objective precision, value neutrality, or even mere instrumentality, Wilcox shows how posthuman assemblages of drones and their human operators work together to perform race and gender, thereby identifying people on the ground as potential “targets” (23-25). Similarly, Ruha Benjamin’s analysis of algorithmic racism (what she calls “the New Jim Code”) leads her to a critique of traditional notions of agency and intentionality that mirror Latour’s insights. She points out that algorithmic racism is often so pernicious because it can occur without any one of its constituent actors (be they robots, algorithms, or human programmers) fully aware of the racist effects they enact (59-66). Safiya Umoja Noble offers a parallel insight about the encoded racism of internet search algorithms, which often build themselves through a “symbiotic” relationship between technology and user (25). The goal of both Benjamin's and Noble’s analyses is not to let humans off the hook but to deepen our understanding of human-technological agency so that we can better engage in anti-racist struggle. In a related vein, Jerry Roziek’s study of school segregation leads him to conclude that critical race theory may benefit from a posthumanist supplement. He traces racism as an object with agency all its own, one that can even become enmeshed in progressive scholarly efforts to critique modes of oppression (80-82). Roziek’s goal is not to disengage from anti-racist scholarship but to develop posthumanist methods that recognize such scholarship’s co-constitutive involvement with racist modes of analysis (82-84).

I concur with such efforts. My own view is that Latour’s work can contribute to them, particularly because it is so focused on similar themes of assemblage, symbiosis, co-constitution, human-technological agency, and the inherent politics of social science research. Accentuating these parallels requires, I believe, a more thorough alignment of ANT and rhetorical theory, one that can add precision, acuity, and leverage to analyses of social structures. The former is the task to which I turn below, showing how rhetorical studies might more fully explore ANT as part of a wider effort to trace posthuman rhetorical becomings.

Tropological Articulation in Rhetoric and ANT

If Latour (in the Walsh interview) explicitly rejects thing-oriented rhetoricity, he also begins to show how such rhetoricity might be re-theorized; for the substitute to rhetoric Latour recommends is also a key concept of rhetorical theory: articulation. He asks Walsh:

If you wanted to shift to articulation instead of [rhetorical] communication, where are the [rhetorical] resources for that?... articulation is philosophy, semiotic, whatever, but it’s not [rhetoric]—again, this is due to my deep ignorance of the field of rhetoric. (415-416)

Let us take Latour’s question seriously: where are the rhetorical resources for a posthuman theory of articulation?[2] For my purposes it makes sense to begin with Nathan Stormer’s study of the concept. Indeed, just like Latour, Stormer describes articulation as a performative process whereby emergent relations are responsible for the association and distinctiveness of compossible entities (261). Stormer explores this process through the canon of arrangement. As he points out, classical rhetoricians saw arrangement requiring composition of membra, as in the articulated “members” or parts of a material body. Stormer’s insights can be supplemented with similar discussions of embodied style from another classical source, the Rhetorica ad Herennium. Its anonymous author identifies a specific figure of speech as an “articulus,” defining it as a series of quickly repeated phrases (each slightly different) that assemble without supplementary conjunctions (Burton; Rhetorica 258). Distinguishing it from the slower concatenation of membra, Anonymous analogizes articulus’ movements with physical articulations:

[Articulus occurs] when single words are set apart by pauses in staccato speech, as follows: “By your vigor, voice, looks you have terrified your adversaries.” …There is a difference in onset between [articulus] and [membra]: [membra] moves upon its object more slowly and less often, [articulus] strikes more quickly and frequently. Accordingly in [membra] it seems that the arm draws back and the hand whirls about to bring the sword to the adversary’s body, while in [articulus] his body is pierced with quick and repeated thrusts. (258)

While the arrangements of articulus and membra communicate meaning, they also seem to have specific ranges and rhythms of physical motion. Though it is possible that Anonymous is only making a metaphorical comparison, ancient rhetoric often equated movements of body and language. Debra Hawhee notes that both Greek athletics and sophistic rhetoric emphasized tendencies similar to Anonymous’ definition of articulus--of physical movement to emerge from rhythmic repetitions and differentiations (141-142). This tendency of repetitional rhythm to emerge through different sequenced positions is critical and implicitly noted in Anonymous’ description. Anonymous says that articulus “strikes” “quickly” upon its target. Movements into and out of different positions manifest across “quick and repeated thrusts.” Hawhee notes that this repetitional difference required the same stylistic precision of both athletes and rhetoricians: “the two kinds of training merge in style as rhetorical training assumes the very dynamic found in [athletic training].... Such attention no doubt is enabled through rhythmic repetition of schemata, a term that may be used to describe a wrestling move, a figure of speech, a particular style or manner, or even gesticulation” (147).

Of course, rhetoric is not the only discipline to study physical style and arrangement as components of structural coherence. Art, architecture, and design could assert equal claims, and Latour develops his account of articulation from process philosophy and semiotics. For rhetoric to show utility to Latourian articulation, it has to contribute something to Latour’s account that his theory does not specify. I believe it can, but to see that benefit we have to carefully delineate Latour’s theory first.

Latour describes articulation as the quality of a network of actants when an emergent entity (be it agency, meaning, or affect) can circulate amidst them while going through the series of transformations required to retain each actant’s distinctiveness (“On Recalling” 15, 17-18, 22; Pandora’s 142-144, 162, 186-187). An example offers clarification. In one of his case studies, Latour follows a group of soil scientists as they assemble a scientific articulation that includes themselves, the soil, and the technologies that bring scientific subject and natural object into closer association. Of special note is an open-topped specimen case called a “pedocomparator,” a grid of small compartments analogous to the graph paper that will record its data. The scientists use the pedocomparator both to gather soil samples and to signal soil dynamics. In doing so, the scientists do not acquire access to a nature beyond their technologically mediated association with the soil. As Joshua Prenosil observes, the soil’s meaning, which is now not just the soil’s alone, becomes more articulated as it is transformed by its association with the pedocomparator (101). When the scientist uses this technology, Latour explains, “[The scientist] does not impose predetermined categories on a shapeless horizon; he loads his pedocomparator with the meaning of the piece of earth … he articulates it” (Pandora’s 50-51). Thus what circulates among soil, scientist, and technology is an emergent meaning that, had other actants joined its articulation, might have been different. These three entities come into closer association not despite their distinctiveness but because meaning is able to circulate amidst them as it goes through transformations that increase their distinctiveness. Later, that meaning will circulate to graph paper, and later still to a scientific article. If that article means anything, it is because meaning flows across the network of distinct actants that associate article and soil. If meaning did not cycle through that articulation, the scientist would become less distinctively scientific and the pedocomparator would become less distinctively technological (126-127). The soil itself would become less distinct; it would have fewer actants with whom to communicate its distinctive nature. All these actants become distinct together (more scientific, technological, and natural) because a contingent “event” of meaning circulates amidst them through the transformations they require (126). For Latour, articulation is the quality of networks of distinct associated actants through which a circulatory event emerges.

Latour goes on to define specific dimensions that define an articulate network’s structural integrity, using terms borrowed from linguistics: “association” and “substitution” (Pandora’s 158; “Berlin” 11-12). We have already seen how these dimensions describe relations between networked actants; the pedocomparator circulates meaning because it simultaneously associates with the earth and substitutes for it. When the scientist graphs the soil’s dynamics, he looks not to the earth but to the pedocomparator, which substitutes for the nature he discerns. That substitution is only possible because the earth can associate with the pedocomparator, which holds soil samples in its compartments. Both axes have to occur together for meaning to circulate (Pandora’s 158, 162). A pedocomparator that could not associate with soil could not function as its substitute. Equally pointless would be an association without substitution. In that case, all that could associate with the earth would be the earth itself, producing an undifferentiated and inarticulate network. The pedocomparator becomes articulate because meaning circulates persistently through the association and substitution it affords. As Latour defines the terms, “Association--which actor can be connected with which other actor? Substitution--which actor can replace which other actor in a given association?” (304). As he describes elsewhere:

The compromise between associations and substitutions is what I call exploring the collective. Any entity is such an exploration, such a series of events, such an experiment, such a proposition of what holds with what, of who holds with whom.... (Latour’s emphasis; 162-163)

We should note Latour’s use of the word “proposition,” a concept he adapts from Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy. In Latour’s work, a network is a proposition because it is sensitive to the potential of emergent entities (e.g. meaning, affect, agency) to circulate within it. An incipient network proposes such emergence. And what defines a successful propositional network is exactly that quality already identified: it is articulate. As Latour puts it (in the context of his work on technoscience), “The question is no longer whether [scientific] statements refer to a state of affairs, but only whether or not [technoscientific] propositions are well articulated” (Pandora’s 303). Latour’s phrasing here—“state of affairs” vs. “well articulated”—hints at another philosophical influence on his concept of articulation: J.L. Austin’s theory of performatives (Inquiry 88-89). Like Austinian performatives, the integrity of articulated events is not determined by preceding states of affairs; articulations are evaluated by whether they felicitously assemble actants while maintaining their distinctiveness. A network’s felicity depends upon whether its “whos” and “whats” afford associations and substitutions that successfully propose an emergent circulatory event (454). Such articulations are marked by tightly integrated but distinct actants, net-worked through the “compromise” of associations and substitutions. Articulation, Latour describes, is an “ontological property of the universe,” the tendency of emergent entities to become and circulate amidst net-works of associating and substituting actants (Pandora’s 3).

As detailed as is Latour’s account of articulation, it begs critical questions that his corpus leaves unanswered, particularly about the relationship between association and substitution. To note that a “compromise” of association and substitution is required in any articulating series is well enough, but what then is the dynamic of that compromise? Latour writes repeatedly that assemblages emerge as a singular movement proceeding across both substitutional and associational axes simultaneously (Latour et al. 34; “Technology” 106-108). He says explicitly that displacement along one axis “requires” displacement along the other, while also insisting that these axial displacements are not to be thought of as separate impulses but coordinate ways to measure a more fundamental dynamic of articulation (“Where” 171, 173; Latour et al. 34). Yet for all Latour’s monistic insistence, he never fully explains how this single dynamic of articulation necessitates the mutual involvement of associational and substitutional displacements. This is not an idle point. Articulation is at the heart of Latour’s ontology and to describe it as “an ontological property of the universe” requires a more detailed account of the singular becoming that enfolds association and substitution.

It is here that tropology can contribute to Latourian theory, principally through Christian Lundberg’s work. Lundberg shows how the axes of structuralist assembly (association and substitution) are better reconceived in terms of two major tropes: metonymy and metaphor. As Lundberg points out, metonymies are tropes of close association, as in a substitution from cause to effect (e.g. metonymically saying “My dog Molly is my pride and joy,” when she is really the cause of those emotional effects) (Lundberg 78-79, 81; Bredin 48). Because causes so closely associate with effects, one can substitute for the other. Metaphors are tropes of substitution, which thereby associate one thing (say, a powerful senator) with an otherwise unassociated other (say, a lion; thus the expression “Lion of the Senate”). These inverted descriptions begin to suggest how Lundberg can theorize what Latour does not, the mutual tropical involvement of metonymic association and metaphoric substitution. Metonymies turn from assumed associations towards the production of substitutions, but that substitutional turn requires the “stands in for” function of metaphor to make any assumed metonymic association durable (Lundberg 79). If you couldn’t substitute causes for effects, the metonymic association affording that substitution wouldn’t be meaningful or persist as a metonymic relation. Similarly, metaphor turns towards metonymic association. We can see this in the classic metonymic association between symbols and signifieds (as when we substitute “the Crown” for the Queen), which thus infolds an associative metonymic turn in metaphor’s ability to symbolize one thing with a fundamentally different other (Lundberg 78-79, 81).

What then to call this creative movement that incessantly turns each rhetorical relation (metaphoric and metonymic) towards the other (Lundberg 79)? Their singular precondition is trope in its literal, original meaning; a basic “turning,” a kind of indeterminacy and transforming. And amidst such turning we are, perhaps unexpectedly, not too far from ANT, as Latour also leverages tropic indeterminacy as articulation’s precondition. In his first book Laboratory Life (co-written with Steve Woolgar) Latour argues that an articulated technoscientific network is akin to any other life-form, but only recognizable as such if we reconsider what life is. For Latour, life is not identifiable as a stable substance. It is an “event” through which local order emerges from an abiding indeterminacy or, as he puts it using trope’s cognate, “entropy” (251). We tend to imagine entropy as inimical to life, but for Latour and Woolgar that is not the case. Life, they argue, is “fed” by swerves, clinamens, and turns--by what we can rhetorically conceive as the tropological (251).

Much like Lundberg, Latour is interested in how articulations emerge from tropic indeterminacies, yet Latour doesn’t theorize the dynamics that relate tropic indeterminacy to the axes of determinate structure (association and substitution). Rhetorical theory’s ability to analyze metaphor and metonymy as mutually infolded turnings offers a better way to see a coherent relationship between tropic articulation and indeterminacy. Given that rhetoric has long positioned itself as a techne of assembling the social amidst indeterminacy and contingency, this account of trope’s articulation of contingent assemblies can supplement ANT’s similar goal.

Additionally, we can augment rhetorical versions of ANT with Latour’s insight that semiotic relations (like metaphor and metonymy) might delineate articulated material gatherings. Indeed, we have already seen how such structural order might emerge from tropic dynamics, in both rhetoric and Latour. We saw it first in the articulus’ assembly. An articulus like “By your vigor, voice, looks you have terrified your adversaries,” turns and changes precisely because a word like “voice” simultaneously associates with and substitutes for “vigor,” just as “looks” associates with and substitutes for “voice.” The figure coheres and articulates so well because what seem like two separate relations are instead a singular turning that resolves itself as a “compromise” of inextricably net-worked metonymic and metaphoric movements. The articulus is the visible remainder of a singular turning circulating through the series.

A similar tropic movement appears in Latour’s pedocomparator. First, the close association between this technology and the soil it contains is also a classic metonymic relation, the association between a container and its contents (as when “a boiling kettle” refers to boiling water (Bredin 48)). But the fact that this metonymic association produces a substitution like “pedocomparator” for “soil” requires it also turn towards metaphor’s substitution of one thing for a completely different other. Seeing how the pedocomparator iterates soil beyond its metonymic association, Latour describes it becoming like very different metaphorical things: “The pedocomparator has made the [earth] into a laboratory phenomenon almost as two-dimensional as a diagram, as readily observed as a map....” (Pandora’s 53). Though Latour is unaware of it, this example is discernible as tropological articulation. The pedocomparator is neither only a mere metaphor nor is it only an insignificant metonymic association. It is the articulate compromise of a tropic turning circulating through the technoscientific assembly, allowing each actant to become both more distinct and connected, more metaphoric and metonymic. If we just see these relations as just associations and substitutions, we have no account of 1) their involvement in each other and 2) that involvement as a preconditional turning resolving itself as an articulated series. Latour provides a fertile way to think of assembled things in terms usually reserved for linguistic relata, while rhetorical theory allows us to see how such relata emerge and articulate amidst tropic indeterminacy.

Weaving these strands together provides a rhetorical ANT that doesn’t attenuate the rhetoricity of contingent assembly by attributing it to the prior suasive influence of individual actants. Attributing suasive influence to separate actants can lead us to think of their individual rhetoricity as prior to their assembly, thus weakening Latour’s efforts to prioritize assembling relations over assembled relata. Even attributing suasive influence to a whole assembly of actants begs the question of whether the tendency to assemble is itself rhetorical. We need to remember Latour’s goal of thing-orienting Austinian performativity. Latour wants to study how articulations “do words with things” (“Berlin”), eventuating felicitously coherent assemblies that have a reality irreducible to prior “states of affairs.” What I argue in the next section is that studying tropological articulation can help observe such becomings, tracing how articulations emerge from turnings too indeterminate to be called prior states of affairs. We are now theoretically equipped to study bump stocks as tropological articulations.

The Bump Stock as Tropological Articulation

As Latour describes using now familiar terminology, “If we study the gun and the citizen as propositions... we realize that neither subject nor object (nor their goals) is fixed. When propositions are articulated, they join into a new proposition. They become ‘someone, something else’” (Pandora’s 180). Though not explicit, we can also see here the twinned movements of trope identified above. A classic metonymic pair traces the close association that inheres between users and tools, with shooters and firearms an exemplary instance. Metonymically referring to a hitman as a “hired gun” leverages that relation. Of course, the very fact that metonymic substitutions turn each pair from a close association towards a figurative representation suggests a simultaneously metaphorical turn. When gun and shooter come into close association, they also, as Latour puts it “become someone, something else.” Metaphor traces this substitutional potential of associated entities to become something irreducible to their constituents.

These are useful examples of tropological relations between users and technologies, but they are a bit too general to give an adequately thing-oriented study of trope. Additionally, they do not quite show how the tropological relations of metaphor and metonymy are involved in each other’s creative turnings. What we need to trace, therefore, is an event where a new articulation emerges between humans and firearms through a tropological event.

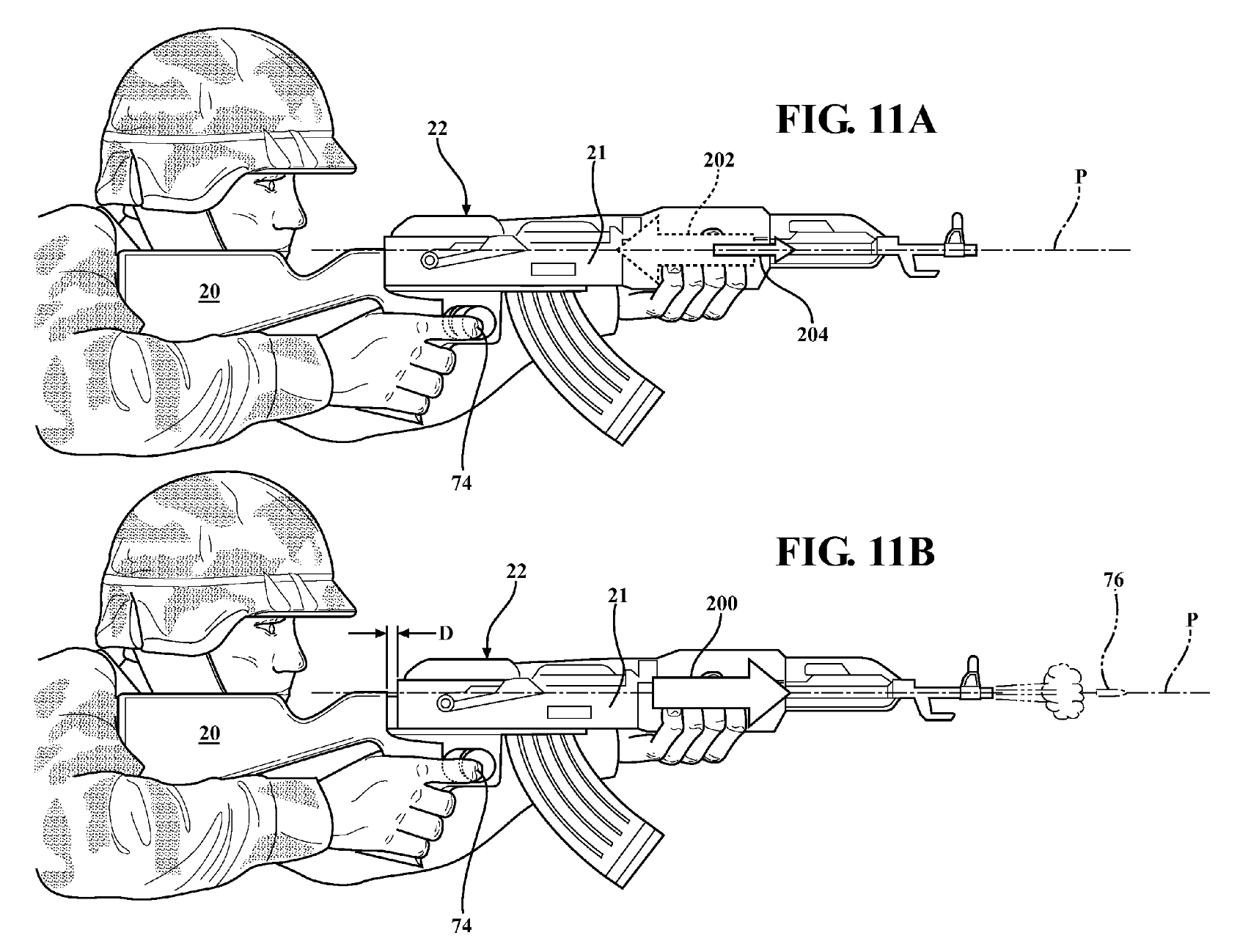

The bump stock offers such a case study. To trace it, we need to begin with a precis on how this technology works (Buchanan et al). In firearms parlance, “stock” refers to the non-mechanical “furniture” surrounding and cradling a rifle’s mechanical components. It’s the part held by the shooter, traditionally wooden (though now often plastic) and shaped to fit into the shooter’s shoulder and hands. The bump stock’s inventor, Bill Akins, realized there was no need for a stock to cradle the rifle’s mechanism firmly. Instead, if the mechanism could slide fore and aft in the stock, that would allow the trigger (along with the rest of the mechanism) to slide forwards and “bump” into a shooter’s immobile trigger finger (instead of the shooter pulling their finger back towards the trigger), thus initiating a firing sequence. Since every shot causes recoil, that would provide energy to slide the whole mechanism rearwards in the stock. Placing a spring in line with this sliding movement, between the rifle’s mechanism and its stock, would capture that rearward energy and rebound the mechanism forward again, pushing the trigger again into the shooter’s finger, initiating a subsequent firing sequence (see figs. 1, 2, and Buchanan et al. for depictions). Akins had devised a way to make a rifle operate cyclically, as machine guns do, but without inserting that cyclic agency inside the gun’s mechanism.

Fig. 1 Slide Fire’s technical drawing depicting the bump stock’s operation (Cottle 8)

Fig. 2 Animation of bump stock function. (Fenix7777)

Users need make no modifications to the existing internal components of their perfectly legal semi-automatic rifles. Instead they could simply append Akins’s spring-loaded bump stock as an external accessory and then fire their guns like otherwise illegal cyclic machine guns. As we will see shortly, there are parallels between this cyclic movement and articulus’ rhythmic repetitions.

First, let’s return to the spring that seems to enable cyclic firing, for it would also be the first bump stock’s legal undoing. When ATF initially ruled Akins’ stocks constituted machine gun parts, it specifically cited the spring and argued that, even though it had been added as an external accessory, it could nonetheless be considered an integral part of the rifle’s mechanism because it was critical to the production of a new machine gun agency (Bureau “Questions”).[3] The decision forced Akins out of business, but another company, Slide Fire Solutions, began developing a similar design inspired partly by Akins’.[4] Slide Fire’s decision to remanufacture the banned device might seem foolhardy, but it was based on a very rhetorical and tropological understanding of firearms regulations. In their original ruling against Akins, ATF said he only needed to surrender his stocks’ springs, as that was the part they believed afforded a machine gun agency (Bureau). If Slide Fire could make a bump stock work without associating a spring, they might be able to, in turn, substitute a legal device for the one that had been restricted. What Slide Fire did, then, is a particular kind of turning movement that Latour calls “delegation” (Pandora’s 187). As Latour might describe it, Akins’ spring had failed the legal “trials” posed by ATF regulations, but if its role could be “delegated” to a legally stronger actant, a new and legal bump stock might able to articulate legally with its human operators (118, 187).

Where to find such a peculiar actant, at once springy but non-machinic, functional but not regulatable? Slide Fire found it in the human operator’s forward arm, which would now associate a muscular, springy, isometric tension with the rifle’s mechanism, rebounding it forward just as Akins' spring had. Users would now be instructed to grab the front of their rifle’s mechanism (usually by gripping at the barrel) and constantly press it forward, just like Akins’ spring (Slide Fire, “Bump Firing”). As Slide Fire writes in their patent application, “the shooter’s arm… acts something like a spring… constantly extending and absorbing the impact of recoil forces” (Cottle 12). In essence, it was now Slide Fire thinking like a Latourian, while simultaneously hoping that ATF would think like an anthropocentrist. Slide Fire realized that there was no superior actant in the network assembled by bump stocks, rifles, and shooters. The network’s agency circulated through a series of actants that articulated certain associations and substitutions without privileging human or non-human action. A human arm can “act” like a spring, and vice versa. And about ATF, Slide Fire was also right; in a decidedly humanist turn, the Bureau ruled that since Slide Fire’s revised design had “no automatically functioning mechanical parts,” it was not a machine gun, its capacities depending upon the human “shooter[’s] constant forward pressure” (Spencer).

But had ATF made a mistake? Even if they believed it was the human shooter activating the device, a Latourian rhetoricity should attune us to the fundamentally tropological agency that persistently and repeatedly circulates amidst shooter, rifle, and bump stock. I believe it can. We can begin tracing that agency in Slide Fire’s patent document, which, at first, seems quite anthropocentric. What causes the stock to work, they argue, are “muscular changes willed by the shooter,” a “volitional act of the shooter,” and an “intentional forward movement,” (Cottle 13, 14). Yet the patent also suggests something more is required. We do not easily convert our arms into reciprocating springs. Doing so is not necessarily an agency we possess. Instead, they say it may require some “practice” with the device, practice that in turn develops “new muscle control techniques” and “previously unknown skills and nuances” (Cottle, 2012, p. 15). The emphasis on “practice” here is important. In ways similar to the preceding discussion of trope, Casey Boyle argues that rhetoric is well attuned to “practice” as a repeated, rhythmic, and serial ontological event, one that precedes any of the “actors” who take it up (546-550). “It is not that a body practices using a tool/object/task,” he writes, “but that an event of practice occurs, exercising an ecology’s tendencies and develops, over time, further capacities for that ecology” (546). Beyond a merely human capacity, therefore, Slide Fire’s patent seems to trace the emergence of something more. What emerges through this practice, they write, is a “rhythm” and a “style.” “The present invention,” they write, “enables a new and exciting rhythmic shooting style” (Cottle 4). If the earlier technical descriptions suggested the human was the controlling agent, here it might seem as if it is the bump stock that “enables.” But a middle position may be most accurate; it is “the rhythmic shooting style” that is “exciting” --literally, setting in motion, instigating, calling forth (“excite”). It is this rhythmic style, they say elsewhere, that while it inheres in the shooter’s muscles, is not the result of the shooter’s determined actions as it precedes their muscular ability to react. We find this in the second-half of the quotation above about the arm’s springiness:

When practicing this method, the shooter’s arm … acts something like a spring … constantly extending and absorbing the impact of recoil forces. Because the firing cycles occur so rapidly in comparison to human reaction times, the user will fall into a natural rhythm of shooting in rapid succession. (Cottle 12)

This cyclic rhythm is not something shooters actively achieve--it occurs faster than their “reaction times.” Instead, users “fall into it.” Of course, it is not just the shooter falling into a rhythm. As described above, the bump stock-equipped rifle cycles rhythmically too, turning back and forth with the shooter. These patent statements are, perhaps, more truthful than they know; the serial rhythm that iteratively articulates the shooter, rifle, and bump stock together is indeed something “natural,” even though it is not located in any of their individual natures. It is that which articulates them together as it circulates amidst them.

But is this rhythmic articulation tropological? Clearly, there is a close association between shooter, bump stock, and rifle, one that cyclically turns and iteratively substitutes a new firing sequence out of the preceding one. Such movement also bears similarity to the turning movement of the articulus, a repetitional series in which each iteration produces energy for subsequent movements. What we still need to find, however, is the precise way these metaphoric substitutions and metonymic associations are rhetorically infolded in each other, a tropological articulation in which shooter and bump stock are turned towards and with each other. We find a trace of this in another technical document important for the assemblage’s performance, a set of “Frequently Asked Questions” instructions provided on Slide Fire’s website. These instructions are important precisely because, as the patent suggests, firing a bump stock is not necessarily something you just do, the result of a skill you already have. Indeed, the fact that Slide Fire addresses operational procedures in a “Frequently Asked Questions” document reinforces this notion that users may not intuitively possess the requisite skill. Such documents are designed to resolve problems that occur after users’ initial attempts reveal operating challenges or operator deficits. How, then, to describe the event that successfully articulates stock and shooter?

The amount of pressure used to push the gun forward has been the biggest problem in regards to the effective use of Slide Fire® stock systems. The amount of force needed is far less than most would assume, and only 4-6 lbs…. This should be just enough to barely pull the trigger, and any extra will counteract the recoil and restrict bolt movement causing miss-feeds or trigger reset failures.... There is generally a two-magazine learning curve and for some it takes a few tries to get the “touch” right. (Slide Fire, “Frequently”)

It is that final and utterly rhetorical bit of language--“the ‘touch’” -- that is so telling. This “touch” is clearly metaphorical, evinced by quotation marks telling us “touch” substitutes for something that more literal and technical words would not quite name. But substituting for what? On the one hand, this “touch” seems to be a type of cause, with previous sentences quantifying it as certain pounds of force shooters should apply. But it also seems a kind of effect, a consequence of practice or “tries” with a bump stock. In describing the amount of practice required, Slide Fire does not specify an amount of time. Instead, “tries” are measured in “magazines,” which hold the set number of cartridges a rifle can fire cyclically before reloading. Besides just a causal force, then, the “touch” is also something shooters “get” from the bump stock, an effect of its cyclic shooting. As a figure, this “touch” seems to hover between cause and effect, between touching and being touched. In this way, the “touch” also evinces a classic metonymic association of cause and effect, and the way one can rhetorically substitute for the other. Once substituted beyond that association, the figure turns into a kind of metaphorical “touch,” but one that, in turn, represents the very metonymic resonance of infolded causes and effects in a recursive, cyclic event of practice.

We see a very similar trope in FAQ instructions for a slightly different Slide Fire model (for less powerful rifles), where the word “feel” plays a role similar to “touch.” Slide Fire writes, “It is absolutely necessary to apply as little forward pressure as possible. It may be necessary to practice different holds or firing techniques before you get used to the feel involved” (“Frequently”). Again, there is a metaphorical turn here, with “the feel” used figuratively to substitute for more forthrightly technical descriptions preceding it. Yet, in the same manner as “the touch,” “the feel” also turns towards a metonymic association of causes and effects, as well as users and instruments. This “feel” involves both the user’s causal act of feeling something out, of practicing “different holds,” and the effect of the instrument’s particular “feel” on that feeling user. What characterizes such a doubled feeling is exactly what Slide Fire says; it is “involved” or, as that word etymologically suggests, both the shooter’s and the stock’s feels are “entangled” and “enfolded” in one another (“involve”). “The feel” is a metaphorical substitute for that metonymic enfolding, a substitution undergirded by the fact that a single “feel” can metaphorically represent either one of the associated metonyms (user and instrument, cause and effect) because each is so deeply enfolded in the feeling of the other. If forced to decide which style--metaphor or metonymy--names the “feel” and “touch” articulating shooter and stock, the answer is trope. It is an event of user and instrument enfolded in the recursive turning of causes and effects. Human and technology are turned together. These are not mere “touchy,” “feely,” subjective impressions ambiguously discerning objective procedures. They are tropes of the cyclical, circulating agency that net-works two distinct and intimately articulated actants. Slide Fire itself says the emergence of this tropological articulation is traceable as a “learning curve,” a turning clinamen of emergent “practice.” Without this turning, this “feel,” this trope--no user, no instrument. The most rhetorical words in Slide Fire’s operating instructions are also, as Latour might say, the most realistic (Pandora’s 153).

Conclusion

We are ready to answer the questions with which we began. What enabled the invention of redesigned functional bump stocks? An affective trope—the technology’s feel as the user feels it. What proves that bump stocks assemble an emergent agency irreducible to their human users alone? The same trope, because the two questions are the same: the rhetorical emergence of this technology and its users is a gathering of feeling circulating among the actants infolded by its articulation (Latour “From”; Rickert, Ambient 228). What subsists amidst these actants is not just a suasive force by which one entity influences the other. It is a persistent turning feeling out capacities of assembly. From the perspective of the theory I have laid out, bump stocks are deeply implicated in the violent capacities they assemble.

In making this case I have likely raised potential concerns that I want to address. First and foremost, the precise affectivity of the bump stock-human assemblage requires further study. To describe it as “exciting” begs the question of exactly what type of physical and emotional investment assembles these actants. Such questions are important, particularly given the violent affects that have historically involved firearms in the broader assembly of American culture. There could well be potential links between the affectivity of firearms use and the social structures associated with gun violence and gun culture. Indeed, scholars have gone a long way towards documenting such a connection. F. Carson Mencken and Paul Froese’s extensive survey research found that a disproportionate number of white men experiencing economic precarity possessed guns as a semiotic marker of “power and identity” (23-24). White male gun owners were also more likely to hold anti-government and/or insurrectionist views, seeing gun use as a symbol of those political sentiments (24). Citing Randall Collin’s work on guns as ritualistic fetishes, Mencken and Froese attribute a kind of material-semiotic agency to firearms, one that echoes Latour’s actant-oriented ontology. They write, “Once embraced as a source of identity and power, the gun can become an object of worship which makes its own demands, no longer simply a tool used for emotional solace but rather a source of sacred meaning” (9; my emphasis). And beyond the symbolic attachment experienced by economically precarious white men, upper-middle class and wealthy white people can also see guns as a material response to imagined threats of black violence. Take Robin Di’Angelo’s work on “white fragility,” in which she argues that white people see firearms possession as a way to articulate racialized fear without directly acknowledging the racism underlying their paranoia (44-45).

These racialized affective investments have been clearly associated with institutionalized firearms violence against communities of color. Aldina Mesic et al. documented that police shootings of African Americans were more likely to occur in states with a higher prevalence of structural racism (112). In a more historical vein, Richard Hofstadter and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz each note that America’s obsession with firearms has some of its earliest and firmest roots in the armed antebellum slave patrols used to capture runaway slaves and prevent insurrection (Hofstadter 3; Dunbar-Ortiz 59-71). Slave patrols had an economic impetus, but, as Angela Davis notes, they were driven by a terroristic desire to commit violence upon black bodies (139-140). Bearing in mind that, as Dunbar-Ortiz notes, some present-day policing practices have their advent in slave patrols, the contemporary relationship between institutional racial violence, firearms, and policing noted by Mesic et al. could mark the continuity of an enduring affective disposition (Dunbar-Ortiz 69-70).

Addressing these questions may go beyond the abilities of Latourian theory, which does not frequently delve into the realm of affect. To acknowledge that aporia is simply to say that ANT can help extend affectivity to posthuman assemblies, but it may not take us as far enough in clarifying it. As I hope to show in future work, other schools of rhetorical criticism may be able to pick up where this analysis leaves off, elucidating why handling firearms “excites” so many users.

A second potential concern I want to address is that my analysis of bump stocks has often focused on the troped language of their technical documents. In doing so, one could argue I have recreated one of the modern segregations Latour critiques: the distinction between words and things. This is a fair concern, but my focus has its reasons and they accord with Latour’s belief that the distinctiveness of words and things is itself an event of articulation. There is a good reason to see the bump stock’s written tropes as part and parcel of the device’s articulate emergence. Recall that Latour bases articulation on Austinian performatives, but in a more holistic sense. Whereas Austin distinguishes between a performative and its contextual felicity conditions, Latour reconceives felicity as the articulate performance of a whole assemblage -- the potential for texts, contextual conditions, and other actants to all become more distinct as they are turned together. Instructions like those examined here offer a good example of this distinctiveness, precisely because they use troped language. “Feel” and “touch” would be ambiguous/infelicitous if they were not articulated with bump stocks. As a user, it would be difficult to get a distinct sense for what “feel” or “touch” means if you couldn’t use them with a bump stock. At the same time, the bump stock also requires its troped instructions if users are going to get a distinct feel for it and make it perform. Making sense of technical things is what instructions do. Austin says non-literal language makes sense precisely because it performs within a felicitous context (142). Latour’s Austinian innovation is to recognize that it is articulation that assembles words and material felicity conditions capable of being (forgive the clunky coinage) “contexed.” “Context” derives from the Latin contextus, meaning “woven together.” We can think of the written tropes analyzed above as one knot in that woven net-work, one place where I felt that the sense circulating amidst technology, user, and text could best be made traceable for readers of a written journal. The other texts cited are equally performative. Slide Fire’s patents and ATF’s legal decisions made bump stocks happen, at least as much as plastic molding. As each document emerged, the bump stock became more a reality. All these texts are inextricable from the bump stock’s performance, just as the bump stock gives a sense of what those texts mean. They articulate together.

Whether this article performs is still a proposition. It will depend on whether other analyses articulate with it. And here I need to address one more potential problem. I have focused on specific tropological dynamics, and one could argue this puts undue limits on future rhetorical deployments of ANT. We should remember, however, that the rhetorical tradition has long noted tropes’ ubiquity and creativity, particularly metaphor’s. Metaphor is an inherently flexible trope, capable of inventing new associations between the most disparate tenors and vehicles. Metonymy is somewhat more constrained to specific pairs, yet those pairs include basic constituents of both ANT and rhetoric: agent and agency, symbol and signified, container (media) and contents (message). Additionally, metonymies exemplify common sense associations. Hugh Bredin argues that new metonymic pairs emerge as common sense changes and can therefore be used to trace latent associations articulating the social (57). The articulus is also an open-ended scheme. We can think of its basic tendency towards assembly as a foundation for more complicated serial schemata including membrum, incrementum, climax, gradatio, auxesis, epistrophe, and anadiplosis. These schemata could describe styles of assembly. Such techniques certainly have constraints but they don’t prevent studies of nonhumans using other methods, or even studying nonhumans’ persuasive effects. Nor do they prevent using Latour to study rhetoric in other ways, as his theory of articulation does not encompass his corpus. They do, however, delineate a dynamic that can clarify both ANT and ANT-inspired rhetorical studies of articulation. Finally, this method lets us use a rhetorical sensitivity for language to study those things we call things with the same voice we use to study those things we call texts. In this way, tracing tropological articulation can give a wider sense of how many different gatherings are rhetorical.

[1] Rhetorical scholarship frequently explores basic human rhetoricity by showing troped figuration intervening in epistemic experience (e.g. Vico; Nietzsche; Burke). This is particularly true of metaphor, which rhetorical studies often describe as an epistemic-linguistic framing (Gross 84; Bakke 53–55, 72–73, 76; Prelli). From a Latourian perspective, the problem with this approach is that metaphor presupposes a natural distinction between tenor and vehicle bridged only by linguistic figuration, often importing values via the vehicle to construct the natural tenor in a new but always metaphorical and, thus, fictional sense (Graves and Graves 398). Latour objects to such epistemological constructionism (Reassembling 88-106). Lundberg also critiques this approach; studying trope epistemologically, he argues, puts the focus back on the persuasive influence of troped perceptions, reducing trope to persuasion (75-77). In contrast, Lundberg recommends studying trope’s formal and ontologically productive dynamics, as opposed to the persuasiveness of any particular troped discourse.

[2] I follow Stormer’s approach to articulation, grounded in science studies and rhetorical theory, as opposed to cultural studies (e.g. Hall; Laclau and Mouffe; Grossberg). Stormer notes that while cultural studies theories of articulation put a similar emphasis on contingent material-discursive assemblies, they often distinguish between materiality and discourse while emphasizing one or the other, with Hall emphasizing materiality and Laclau and Mouffe emphasizing discursivity (Stormer 280; Hall 145-148). Latour, however, wants to explain the very distinguishing of materiality and discourse as an articulating performance. Grossberg’s Deleuzian approach hews closer to Latour’s and Stormer’s, particularly in its rejection of a priori distinctions between materiality and discourse (We 47-52). My decision to start with Stormer’s rhetorical approach stems from his emphasis on articulation as performative, a quality likewise critical for Latour.

[3] The controlling law in this case, the National Firearms Act, defines “machine gun” liberally to include both weapons originally designed as machine guns and parts designed to convert weapons into machine guns (Bureau “National”). The ATF used the latter definition to classify Akins’ spring as a machine gun, a particularly Latourian move in that it assesses a node/part of a network by the agency it both attains in and affords the network.

[4] Akins actually tried marketing a springless version of his bump stock but was not as successful as Slide Fire, which focused on producing models for increasingly popular military-grade semi-automatic weapons (e.g. AR-15’s and AK-47’s). It is difficult to say whether Akins or Slide Fire decided to remanufacture the device solely for financial gain. Akins described political motivations behind his decision, seeing the bump stock as part of an effort to advance 2nd Amendment rights. It is also possible that both Akins and Slide Fire were symbolically invested in advancing a military ethos within civil society. Slide Fire, for instance, used a diagram of a soldier firing their device as part of their patent application, even though the patent described the device as recreational (see fig. 1). Akins likewise acknowledged that the idea for his device was initially inspired by military anti-aircraft machine guns (Ax).

Anonymous. Rhetorica ad Herennium. The Rhetorical Tradition, edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, 241-282.

Ax, Joseph. “Inventor of 'Bump Stock' Spent Years Fighting for Device, and Lost.” Reuters, 6 October 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lasvegas-shooting-guns/inventor-of-bump-stock-spent-years-fighting-for-device-and-lost-idUSKBN1CB2TF.

Baake, Kenneth. Metaphor and Knowledge. The State University of New York Press, 2003.

Bay, Jennifer. “In Defense of Rhetoric, Plants, and New Materialism.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly vol. 47, no. 5, 2017, pp. 437-448.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity, 2019.

Boyle, Casey. “Writing and Rhetoric and/as Posthuman Practice.” College English, vol. 78, no. 6, 2016, pp. 532-554.

Brown, James and Nathaniel Rivers. “Encomium of QWERTY.” Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, edited by Scot Barnett and Casey Boyle, University of Alabama Press, 2016, 215-225.

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. “Questions and Answers for the Akins Accelerator.” 2006, https://web.archive.org/web/20090320224054/https://www.atf.gov/alcohol/info/revrule/rules/2006-2_q_and_a.pdf

---. “National Firearms Act Definitions - machine gun.” 2016. https://www.atf.gov/firearms/firearms-guides-importation-verification-firearms-national-firearms-act-definitions-0.

Burke, Kenneth. “Four Master Tropes.” The Kenyon Review, vol. 3, no. 4, 1941, pp. 421-438.

Bredin, Hugh. “Metonymy.” Poetics Today, vol. 5, no. 1, 1984, pp. 45-58.

Buchanan, Larry et al. “What Is a Bump Stock and How Does It Work?” The New York Times, 28 March 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/04/us/bump-stock-las-vegas-gun.html.

Burton, Gideon. “Articulus.” Silva Rhetoricae. 2007, http://rhetoric.byu.edu/.

Collins, Randall. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton University Press, 2004.

Cooper, Marilyn. “The New Ontology of Persuasion.” Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, edited by Scott Barnett and Casey Boyle, University of Alabama Press, 2016, pp. 17-29.

Cottle, Jeremiah. “Method of Shooting a Semi-Automatic Firearm.” US 8127658B1. United States Patent and Trademark Office, 6 March 2012, https://patents.google.com/patent/US8127658B1/en.

Davis, Angela. Policing the Black Man: Arrest, Prosecution, and Imprisonment. Vintage, 2018.

DiAngelo, Robin. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard to Talk to White People About Racism. Beacon Press, 2018.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment. City Lights Books, 2018.

“excite, v.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, 2018, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/65795?redirectedFrom=excite.

Graham, S. Scott. “Object Oriented Ontology’s Binary Duplication and the Promise of Thing-Oriented Ontologies.” Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, edited by Scott Barnett and Casey Boyle, University of Alabama Press, 2016, pp. 108-124.

Graves, Heather and Roger Graves. “Masters, Slaves, and Infant Mortality: Language Challenges for Technical Editing.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 4, 1998, pp. 389-414.

Greene, Jacob. “From Augmentation to Articulation: (Hyper)linking the Locations of Public Writing.” enculturation no. 24, 2017. http://enculturation.net/from_augmentation_to_articulation.

Gross, Alan. The Rhetoric of Science. Harvard University Press, 1990.

Grossberg, Lawrence. We Gotta Get Out of this Place. Routledge, 1992.

Hall, Stuart. “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall.” Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuang-Hsing Chen, Routledge, 2005. pp. 131-150.

Hawhee, Deborah. Bodily Arts: Rhetoric and Athletics in Ancient Greece. University of Texas Press, 2004.

Hofstadter, Richard. “America as a Gun Culture.” American Heritage. https://www.americanheritage.com/america-gun-culture#1.

“involved, v.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, 2018, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/99206?redirectedFrom=involve.

Laclau, Ernesto and Chantal Mouffe. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. Verso, 2001.

Latour, Bruno. The Pasteurization of France. Harvard University Press, 1988.

---“Technology is Society Made Durable.” The Sociological Review, vol. 38, no. 1, 1990, pp. 103-131.

---. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Harvard University Press, 1999.

---. “The Berlin Key or How to Do Words with Things.” Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture, edited by P.M. Graves-Brown, Routledge, 2000, pp. 10-21.

---. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences Into Democracy. Harvard University Press, 2004

---. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press, 2005.

---. “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik.” Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, MIT Press, 2005, pp. 4-31.

---. “Where are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts.” Technology and Society: Building our Sociotechnical Future, edited by Deborah Johnson and James Wetmore, MIT Press, 2008, pp. 151-180.

---. An Inquiry into Modes of Existence. Harvard University Press, 2013.

---. Interview by Lynda Walsh. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 5, 2017, pp. 403-424.

Latour, Bruno, et. al. “A Note on Socio-Technical Graphs.” Social Studies of Science, vol. 22, no. 1, 1992, pp. 33-57.

Latour, Bruno and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton University Press, 1986.

Lundberg, Christian. Lacan in Public: Psychoanalysis and the Science of Rhetoric, The University of Alabama Press, 2012.

Lynch, Paul and Nathaniel Rivers. “Do You Believe in Rhetoric and Composition?” Thinking with Bruno Latour in Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Paul Lynch and Nathaniel Rivers, Southern Illinois University Press, 2015, pp. 1-19.

Mencken, F. Carson, and Paul Froese. “Gun Culture in Action.” Social Problems, vol. 66, no. 1, 2019, pp. 3–27, doi:10.1093/socpro/spx040.

Mesic, Aldina, et al. “The Relationship Between Structural Racism and Black-White Disparities in Fatal Police Shootings at the State Level.” Journal of the National Medical Association, vol. 110, no. 2, 2018, pp. 106–16, doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2017.12.002.

Muckelbauer, John. “Implicit Paradigms of Rhetoric: Aristotelian, Cultural, and Heliotropic.” Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, edited by Scott Barnett and Casey Boyle, University of Alabama Press, 2016, pp. 30-41.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. On Truth and Untruth, translated by Taylor Carmen. Harper Collins, 2010.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press, 2018.

Pflugfelder, Ehren. “Is No One at the Wheel? Nonhuman Agency and Agentive Movement.” Thinking with Bruno Latour in Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Paul Lynch and Nathaniel Rivers, Southern Illinois University Press, 2015, pp. 115-131.

Pheonix7777. “Bump Fire Animation” Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bump_fire_animation.gif.

Prelli, Lawrence. A Rhetoric of Science. University of South Carolina Press, 1989.

Prenosil, Joshua. “Bruno Latour Is a Rhetorician of Inartistic Proofs.” Thinking with Bruno Latour in Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Paul Lynch and Nathaniel Rivers, Southern Illinois University Press, 2015, pp. 97-114.

Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. Pittsburgh University Press, 2013.

---. “The Whole of the Moon: Latour, Context, and the Problem of Holism.” Thinking with Bruno Latour in Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Paul Lynch and Nathaniel Rivers, Southern Illinois University Press, 2015, pp. 135-150.

Rivers, Nathaniel. “Anchirhetoricis Latouri.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 5, 2017, pp. 424-431.

Rosiek, Jerry. “Critical Race Theory Meets Posthumanism: Lessons from a Study of Racial Resegregation in Public Schools.” Race Ethnicity and Education, vol. 22, no. 1, 2019, pp. 73–92, doi:10.1080/13613324.2018.1468746.

Slide Fire. “Bump Firing.” https://web.archive.org/web/20170720121404/http://www.slidefire.com/how-it-works.

---. “Frequently Asked Questions.” https://web.archive.org/web/20170714000017/http://www.slidefire.com/faq.

Spencer, John. Letter to Slide Fire. 7 June 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20130329144344/http://www.slidefire.com/downloads/BATFE.pdf.

Stormer, Nathan. “Articulation: A Working Paper on Rhetoric and Taxis.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 90, no. 3, 2004, pp. 257-284.

Vasquez, Richard. Letter to Thomas Bowers. 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20070506102403/http://www.firefaster.com:80/documentation.html.

Vico, Giambattista. The New Science, translated by Thomas Bergin and Max Fisch. Cornell University Press, 1970.

Wilcox, Lauren. “Embodying Algorithmic War: Gender, Race, and the Posthuman in Drone Warfare.” Security Dialogue, vol. 48, no. 1, 2017, pp. 11–28, doi:10.1177/0967010616657947.