Karrieann Soto Vega, University of Kentucky

(Published November 10, 2020)

If we ask our students to document and explain contemporary circumstances of climate change, they may be tempted to focus on the most recent climate disaster, regardless of where it took place or the socio-political conditions that structure the conditions for disaster. As Danielle Endres notes, “environmental rhetoric scholars continue to confront environmental injustices and ecosystem destruction by examining, deconstructing, and composing anew human relationships to the environment” (315). It is clear, then, that rhetoricians can address climate change in both the classroom and in scholarship. However, in continuing to press for rhetorics and literacies of climate change, we ought to be attuned to ethical questions regarding the examples we choose in our research and pedagogy. In this essay I emphasize the importance of attending to colonial causes and consequences in studying climate change by applying a decolonial and historical method to environmental justice activism in Puerto Rico. Considering that the archipelago has been affected by climate change more than any other nation-state or territory in the entire world (Reichard), it is an appealing location to turn to in environmental rhetoric criticism; but its peoples should be at the forefront when delineating a history of the conditions and contestations of climate injustice in that Caribbean space. To do so, I offer a decolonial approach to studying rhetorics of climate change and a way forward in the quest for engaging in research that arcs towards climate justice, while exposing the injustices associated with climate change-induced catastrophes like Hurricane Maria.

Catastrophes caused by atmospheric events such as hurricanes become exceptionally disastrous if the societal conditions of the particular contexts exacerbate already-existing inequities during recovery efforts. This was certainly the case for Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria hit the territory in 2017. Late geographer Neil Smith’s adage lives on, unfortunately, as the conditions in Puerto Rico still prove that “there is no such thing as a natural disaster” (Perry; Smith). To be clear, the perspective provided in this article points to convergences in the ways that Puerto Rico has not fully or swiftly been able to recover from the damage caused by Hurricane Maria, but also an ongoing recession, insurmountable debt, and coloniality.

To fully trace the development of human-environment interaction, the environment in Puerto Rico must be understood more broadly, politically and historically, not solely in terms of disaster management. As Laura Weiss, Marisol LeBrón, and Michelle Chase wrote in 2018, “the timing could not have been worse:”

Puerto Rico is in the midst of one of the worst recessions in its history, under the thumb of an undemocratically installed financial control board, called ‘la junta’ by locals, and struggling against austerity and the ongoing legacy of colonization and limited self-governance (. . .) In response to Puerto Rico’s calls for aid, the federal administration has framed it as unworthy of U.S. assistance, holding Puerto Rico’s economy hostage to its own remedy to the recession—from the privatization of its electric grid to opening up the economy to predatory investors and transnational wealth—which will only exacerbate problems the nation faces. (109)

Given this exigence, Weiss, Lebrón, and Chase dedicated a special issue of NACLA—Report on the Americas to studying the ways the Caribbean region is affected by colonialism, capitalism, and climate change.

Figure 1. Screenshot of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s reference to Hurricane Maria's impact on Puerto Ricans. Photograph by author, from The Intercept video (Klein, “A Message”).

Two of the three conditions illuminated by Weiss, LeBrón, and Chase—namely, capitalism and climate change—feature in the explanation of the “Green New Deal” proposed by U.S. Congresswoman, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in her descriptions of the impetus for her economic and political proposition. In an illustrated video for The Intercept, “A Message from the Future with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,” she tells the story of how she felt the devastation of her parents’ homeland as a catalyst to pass legislation providing a radical shift in the way we live our lives (Klein, “A Message”). In her extended explanation of the video, which promotes the Green New Deal proposed by Ocasio-Cortez, Naomi Klein describes how Ocasio-Cortez was inspired by the 1930s New Deal artistic and promotional material used by an FDR administration that wanted to imagine what the future would be like. In the video, a future Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tells the story of how and why the Green New Deal was passed. The script for the short film was developed by Ocasio-Cortez and Avi Lewis, who had worked with Klein in the documentary for “This Changes Everything,” and the illustrations were the creation of Molly Crabapple. Both Ocasio-Cortez and Crabapple claim Puerto Rican heritage, which may explain why they included a short reference to how Hurricane Maria’s impact on Puerto Rico confirmed their concerns about climate change. In other words, these artists and government officials use contemporary climate catastrophes to undergird policies that aim to address the increasingly detrimental conditions of climate change. Yet in this process, and in this very brief textual instance, they do not bring up Puerto Rico’s colonial condition. It would be tempting, then, for scholar-teachers andstudents of rhetoric to make a similar mistake.

Considering the ways in which Puerto Rico is featured as an inspiration for policies (or scholarship) regarding climate change prompts attention to the historical development of environmental exploitation linked to colonial capitalism, as well as the persistence of Puerto Rican resistance. A decolonial approach to studying rhetorics of climate change encourages us to consider historical intervention as a way to counteract the presentism[1] that currently pervades discussions of potential solutions to climate crises evident in the rhetorical ecologies regarding “green” policy proposals. Similar to the ways in which political figures like Ocasio-Cortez use Puerto Rico as an example of climate crisis, scholars of rhetoric, writing, and communication may feel inclined to feature this and other recently affected contexts in the Caribbean (or elsewhere) as part of their exploration of how climate change manifests contemporarily. In doing so, they may also neglect to emphasize the significance and adverse impacts of colonial capitalism in climate crises. I argue that Rhetoric and Composition scholars should question the ways in which addressing understudied geopolitical contexts as “new” or “timely” without highlighting colonial histories and grassroots activism in those locales, or the interdisciplinary work of scholars who embody such ethnic and racial identities, replicates colonial configurations of the U.S. academy. Not only does this decontextualized concern ignore the intellectual and activist labor of those embodying the struggle, but it also ignores histories that continue to be disregarded in the construction of the U.S. academy and distinct disciplines like Rhetoric and Composition as a “pioneer” of knowledge.

I am thus issuing a concern about the ways we do our research that is often replicated in our teaching—when we jump on a bandwagon of kairotic appeal without a grounded understanding of place, or when we think of research as timely, addressing issues like recent climate crises but don’t know or acknowledge the (anti)colonial histories of the place, specifically, that of grassroots activists, the history of the struggle, and the embodied day to day experience of such struggle. According to Angela Haas, “decolonial methodologies and pedagogies serve to (a) redress colonial influences on perceptions of people, literacy, language, culture, and community and the relationships therein and (b) support the coexistence of cultures, languages, literacies, memories, histories, places, and spaces—and encourage respectful and reciprocal dialogue between and across them” (297). In this essay I illustrate the importance of attending to both the causes of climate change and the consequent responses by those affected, contributing a decolonial approach to the study of environmental justice rhetorics, especially those situated in overtly colonial contexts.

Decolonial Approaches to Environmental Justice Rhetorics

If rhetoricians are to take calls for climate justice seriously, a collection of studies on rhetorics and literacies of climate change must account for how coloniality figures into developing scholarly understandings of—and our subsequent impact on—those who most endure these processes. Decoloniality, as an epistemological project (Ruiz and Sánchez), provides theoretical language for a rigorous historical analysis that would stave off the presentism evident in media portrayals and policy proposals addressing climate change, such as the example of Ocasio-Cortez above. Besides highlighting coloniality as an explanation for the so-called (post)modern realization of a sudden “fragmentation” within communication and rhetorical theory (Wanzer), decolonial rhetorics simultaneously point to the erasure of existing ontologies prior to the establishment of theories from colonial modernity, providing an alternative set of rhetorics regarding life “elsewhere and otherwise” (Baca and García), an opportunity to “delink” stories of nation state formation not accounting for indigeneity (Powell) or all of those affected by settler colonial processes.

Practicing a decolonial approach, in this piece I delineate “on the ground” activist efforts to address and counter climate injustice in Puerto Rico prior to the impact of Hurricane Maria in 2017. Exploring the case of this Caribbean U.S. territory from a decolonial angle allows me to counter the assumption of top-down approaches from U.S. American scholars who suddenly feel compelled to study cases outside of the purview of the contiguous U.S. academy without first considering the already existing local contexts for activism. Therefore, the work I focus on here is explicitly connected to environmental concerns and ongoing sovereignty struggles. Put simply, we cannot talk about climate change without talking about long standing colonialism and grassroots decolonial struggles.

In Rhetoric and Composition, we may be moved to identify a site such as Puerto Rico—associated with, but not a part of, the contiguous U.S. imaginary—as one that must be studied, helped, and/or documented, prompted by empty associations of citizenry (e.g., “Puerto Ricans are ‘Americans’”) or realizing the “rich” potential for study. Indeed, the historical development of a political relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States has been framed as interventionist ever since the Spanish-American War, when the U.S. gained control over the territory. As Tiara Na’puti indicates about Guåhan (Guam), a number of the island territories under U.S. governmental control are enmeshed with the histories and consequences of militarism. In spite of this fraught relationship, visibility is a problem for the numerous territories hidden from contemporary cartographic and citizenry conceptions of the nation, which are based on skewed understandings of relationships between the U.S. of America and other global/foreign/international because-outside-of territories, successfully hiding an empire (Immerwahr). In other words, maps (literal and imaginary) of the United States that don’t include all of its political territories perpetuate a conception of U.S. American exceptionalism that is limited to the contiguous states in North America and, therefore, obfuscate its imperialist history.

Moreover, as a Puerto Rican myself, I find that calls for, and attempts to document Puerto Rican tragedies simply for the sake of visibility border on disaster porn—a fetishization of representations of climate disaster that obscure the root causes of climate change and its impact on colonized subjects. Admittedly, there is also a sense of skepticism amongst those of us who have been following the tragic consequences of “benevolent” U.S. experimentation/study involving Puerto Rico/Puerto Ricans: from cancer (Immerwahr) to birth control (Briggs), industrialization projects like Operation Bootstrap (Berman Santana; Villanueva) and racializing infrastructure design (Dinzey-Flores), even crypto-colonialism (Bonilla, “For Investors”). Thus, my work here aims to rhetorically historicize and bring further light into the environmental (in)justice and activism that has existed in Puerto Rico long before Hurricane Maria and the contemporary debate over climate change.

Similar to the way Damián Baca and Romeo García survey the development of a decolonial perspective in Rhetoric and Composition, it is important to acknowledge the literature that approximates decolonial approaches to environmental justice rhetoric. Unfortunately, not much of the already-limited pool of scholarship in the field of environmental justice rhetorics focuses on rhetorics of climate change in relation to colonial concerns. Among the most recent, Donnie Johnson Sackey’s “An Environmental Justice Paradigm for Technical Communication” surveys several theoretical approaches that, he argues, “should factor heavily in the ways we approach mitigation of communication issues surrounding environmental concerns” (139). And yet, colonialism is not part of his scope. However, his explanations of the goals of each theoretical approach—feminist materialism, feminist political ecology, ecofeminism, and environmental justice—aim to foreground an attention to the environment in justice-oriented analytical work. As Sackey states, “if the act of questioning space and arrangement is the analysis of the dynamics of culture through the understanding of power via race, gender, economic, and ableist privilege, then attempts to reorder relations through rhetoric and writing becomes the work of justice—environmental justice” (156). In my conception, from a decolonial approach, the work of environmental justice rhetoric ought to attend to coloniality as it seeps into other manifestations of power imbalances, what the Combahee River Collective called “interlocking” systems of oppression and privilege (271); therefore, my decolonial approach is also informed by feminist theory.

My approach approximates Eileen Schell’s transnational feminist rhetoric conceptualization of the Green Belt Movement; in particular, her observation that “local, national, international press emphasizes the aftermath of natural disasters, the destruction and death toll, not the string of economic and environmental choices that led to the root causes of these ‘natural’ disasters” (585). As this quote suggests, in many cases, histories of colonialism shape how environmental injustices occur, as well as the oppositional activisms that link environmental exploitation to colonialism. These historical developments are certainly illuminated by climate catastrophes, such as the case of Hurricane Maria in 2017 and its devastating impact on the geopolitical location of Puerto Rico, but they are not exclusively tied to that moment.

For example, due to the massive damage to the energy grid all throughout the archipelago, people were left without electricity for extended periods of time—weeks, months, even years. That precarity certainly affected many Puerto Ricans, some of whom depended on machines or refrigerated medicine to stay alive (Embedded). Policy regarding so-called “green” energy approaches enacted by the Puerto Rican government after the fact is thus presumably motivated by the effects of Hurricane Maria (Bade; Ellsmoor; Mock). And yet, the precarity of the energy structures in Puerto Rico had been identified as an issue long before the hurricane by several “green energy” activist efforts. As Catalina de Onís writes, “many social movement actors and energy studies scholars [have] engaged in long-time struggles for alternatives to imported fossil fuels and centralized systems that deny community member control over their own energy futures” (“Energy Colonialism” 1). Both Schell and de Onís support an attention to systems of oppression (i.e. capitalist colonialism) and the struggles against their repercussions, which are necessary in a decolonial rhetoric approach to environmental justice.

To reiterate, the rhetorics of climate change and environmental justice concerns in this context extend beyond fossil fuel dependence. A decolonial method for research attending to colonial causes and consequences in environmental justice rhetorics delineates the history of the connections between colonial capitalist exploitation, activist resistance, and resulting crises of climate change, emphasizing the voice and experience of agents of change from the ground up. Therefore, in the following section I explore decolonial rhetorics of environmental justice that have been evident in the zeitgeist of Puerto Rican environmental movements in the 1960s, the anti-military activism in municipal island towns in the archipelago, and close with a brief glimpse at the ways in which these earlier movements have reverberated to form multipronged efforts at sustainable, intersectional and environmentally just community practices that address climate change.

Environmental Concerns Connected to Coloniality

The following decolonial rhetorical history of resistance to environmental exploitation in Puerto Rico, as it is entangled by colonialism, aims to provide a corrective to decontextualized renditions of the territory and an example of how Rhetoric and Composition scholars can engage multifaceted approaches in undertaking climate justice research, thus avoiding the potential for presentism. According to the UN, climate justice “looks at the climate crisis through a human rights lens and on the belief that by working together we can create a better future for present and future generations” (United Nations). But outside of a human rights framework, which has been sufficiently critiqued by transnational feminist rhetoric scholars like Wendy Hesford and Rebecca Dingo, the connections of capitalism and climate change are a significant factor to consider as part of the correlation between colonialism and climate disaster. As Naomi Klein wrote in The Battle for Paradise, the shock doctrine has been present for quite some time in the Caribbean archipelago. A shock doctrine would entail a series of economic and political policies put in place in contexts where there has been some kind of crisis, and where the proposed “solutions” prioritize free-market economies and exacerbate already-existing inequities (Solis). As I have pointed out here and elsewhere[2] however, the battle for paradise has been a long-time-happening, which is why a decolonial approach is most warranted.

Environmental concerns connected to coloniality are often linked to capitalist formation. One instance of this dynamic is the U.S. implementation of industrialization projects in Puerto Rico, such as Operation Bootstrap, first implemented in the post-war era. According to Deborah Berman Santana, “‘Operation Bootstrap’ was the first Third-World, export-led-industrialization development program and was used as a blueprint for similar programs throughout the world” (26, Kicking Off the Bootstraps). Berman Santana also suggests that beyond it being an economic strategy, Operation Bootstrap was a political strategy for the first Puerto Rican elected governor to demonstrate allegiance to the U.S. economic system. Another part of the post-war expansionist economic program for the U.S. was to extend permits for mining companies to be based in Puerto Rico. Therefore, in the 1960s, the environmental movement “arose in response to various manifestations of Puerto Rico’s still-colonial political status and dependent economic development strategy” (Berman Santana, “Colonialism, Resistance” 3). Early on, Puerto Rican nationalist groups aimed to maintain the right to engage in open pit mining for the future of the republic, while “The Socialist League was the only organization that rejected mining entirely even in a future independent republic, claiming that ecological impacts would ‘exterminate’ the country” (García López et al. 93). The mining project was defeated in 1968, after protesters incorporated an explicit attention to the environmental impacts of mining.

Puerto Rican political parties at the time were able to articulate different positions regarding economic propositions like open pit mining, but grassroots groups were the ones acting to counter them through activism and environmentally oriented collective action. One such group has been Casa Pueblo. As Gustavo García López, Irina Velicu and Giacomo D’Aliza explain, Casa Pueblo was formed in response to the reappearance of the open pit mining proposal that was struck down in 1968, but which was resumed in 1980, at a size twice as large as the original proposal, covering 36,000 hectares (93). With a socialist orientation, they organized and mobilized thousands of people to eventually succeed in stopping the project once again in 1995. What’s more, Casa Pueblo successfully advocated for environmental policy reform with the passing of a law that would prohibit open pit mining in Puerto Rico. Casa Pueblo activists were once again active in protesting against a proposed pipeline in 2010, this time joining labor unions during a May Day protest that highlighted the pipeline as an environmental problem, “making it also about the perversity of capital accumulation strategies hidden as false solutions to the country’s energy problems and the implications for working class families” (García López et al. 98). Their socialist rhetorical approach is therefore oriented to claim the well-being of the land for the well-being of the Puerto Rican people who would be most affected. However, as significant as Casa Pueblo’s rhetorical and political impact has been for the continuance of movements countering climate change, they are not the only group or environmental movement that is explicitly coupled to sovereignty struggles.

The attempts in the 1960s to establish open pit mines in Puerto Rico were also countered by groups such as Movimiento Pro-Independencia (Pro-Independence Movement). At that time, this group was involved in other environmentally oriented claims tied to sovereignty efforts—namely, militarism. As César Ayala and Rafael Bernabé indicate, “Overlapping with the new independence, student, and environmental movements, the late 1960s witnessed initiatives to protest the presence of the U.S. Navy in Culebra” (231). In other words, these movements coalesced in relation to countering militarism, which they knew would ultimately have an effect on the environmental state of Puerto Rico. Culebra’s was one of the three massive U.S. Navy military posts located in the eastern parts of the Puerto Rican archipelago—the other two being the town of Ceiba and the municipal island town of Vieques. The U.S. Navy had been established in Culebra in 1923, but in the first half of the 1970s decade, it was physically occupied by activists, many of them pro-independence leaders, such as Ruben Berríos, until president Ford “ordered the Navy to abandon Culebra in 1975,” as Ayala and Bernabé recount (231). These historical renditions connect the development of a pro-independence political movement countering U.S. militarism and occupation in Puerto Rico, while emphasizing their environmental impact on the archipelago’s land and sea. Once again, interlocking systems of oppression are approached through an anticolonial strategy.

Continuing to attend to the impact of U.S. militarism on Puerto Rico’s sovereignty and its environment, pro-independence groups proved to be relentless until they could also get the U.S. Navy out of Vieques. It wasn’t until 2003 when the federal government officially announced it would cease using the territory for bombing target practice. Having lived through this event, I recall how, towards the culmination of civil disobedience efforts, the municipal island town was visited by celebrities such as Ricky Martin and Robert Kennedy Jr., among others, in support of the demilitarization of Vieques.

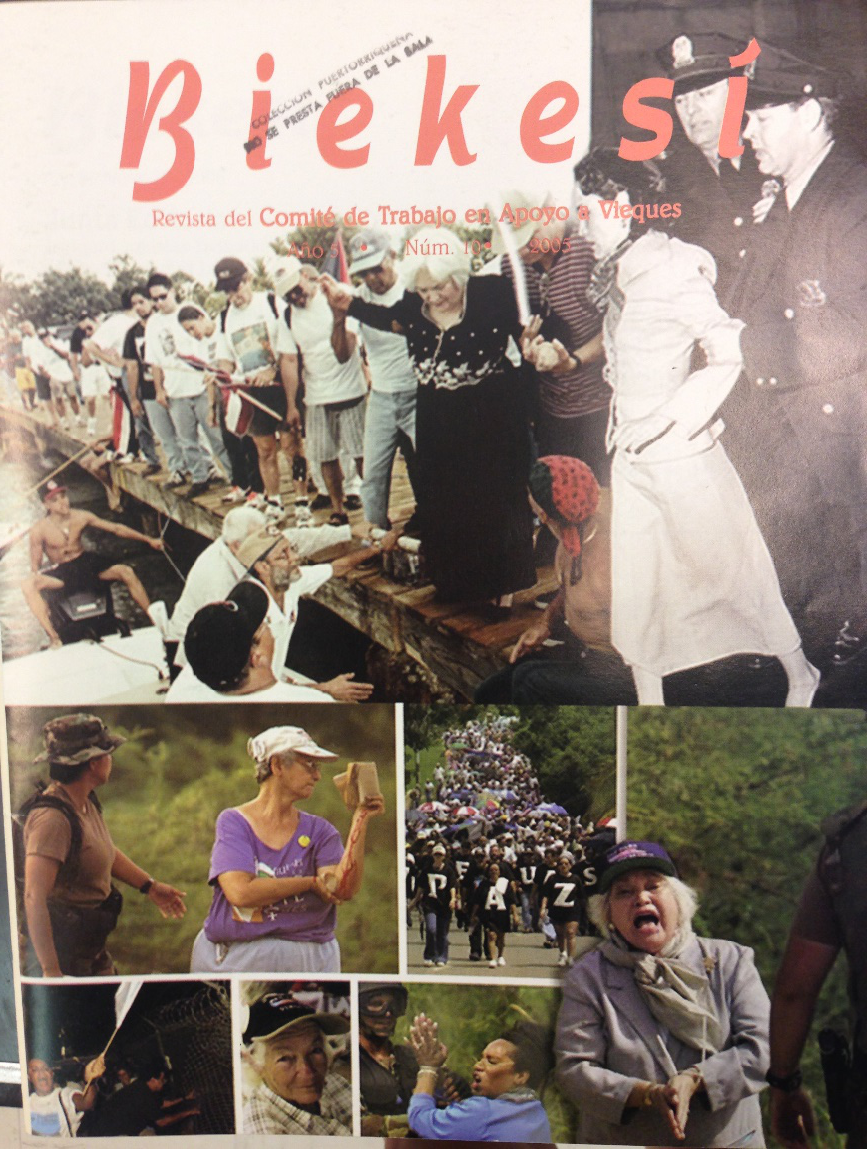

What was not much of a feature in the media coverage about the people of Vieques versus the U.S. Navy ordeal was the importance of Puerto Rican nationalist figures visiting and participating in demonstrations against the U.S. Navy, some of whom were even arrested (Backiel).[3] One such nationalist figure was Lolita Lebrón—the subject of my dissertation work, a feminist rhetorical history project on her rhetorics of defiance against U.S. empire. As can be seen in Figure 2, the Comité de Trabajo en Apoyo a Vieques (Working Committee in Support of Vieques) featured Lolita Lebrón’s participation in their promotional literature. On the cover, there are images of Lebrón juxtaposed beside one another. One image shows Lebrón being supported by many of the people who came to greet her while protesting in Vieques; the other image shows her during her 1954 arrest after an armed assault against the U.S. Congress. The collage therefore shows her history and legacy in sovereignty and environmental justice.

Figure 2. Archival Research, University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras. Biekesí: A Magazine Devoted to Supporting Vieques, featuring a cover page with images of Lolita Lebrón. Photograph by author.

Clearly, her enduring ethos as a devoted revolutionary in support of Puerto Rico’s liberation provided the group with credibility regarding their rejection of the United States’ military presence in Vieques, therefore rhetorically framed as a sovereignty concern. A decolonial rhetorical approach to environmental justice allows us to see how her participation is representative of a long-standing fight against the U.S. as a colonial capitalist state, which exploits not only the people in this occupied territory, but also its land, sea, and overall life in the archipelago.

Although the Navy stopped using close to half of the municipality’s geopolitical territories for target practice, their cleanup of live ammunition has been so slow that even after Hurricane Maria there have been instances of bombs detonating in the sea (where people catch the fish that feed them), and cancer remains rampant—with 27% higher rates than the big island (Bayne and Dieppa). In short, in spite of the presence and connection of sovereignty struggles with environmental activism and concerns, the continued colonial condition still affords the U.S. military with ample space for exploitation. For a complete environmental rhetorical analysis to take place, all of these concerns must be included in a contextualization of climate (in)justice in Puerto Rico.

Creating [Transnational and Intersectional] Futures by Revisiting Decolonial Pasts

From my brief survey of environmental concerns connected to coloniality in Puerto Rico, we can see the importance of rhetorically linking sovereignty and economic development with environmentally detrimental initiatives and a socialist orientation prioritizing the well-being of the people and the environment regardless of political status. Grassroots groups like Casa Pueblo continued to push their activism to account for the problematic of extractivist energy propositions by U.S.-based companies, and they successfully incorporated an attention to policies governing land-use, once again prioritizing Puerto Rican sovereignty and self-sufficiency—which is why post-Maria, they were one of the few places in all of Puerto Rico that had access to renewable energy sources (Caro González). Pro-independence groups have also contributed environmentally oriented claims based on sovereignty, such as U.S. militarization on the archipelago. While Tiara Na’puti focuses on “the rhetorical power of remapping informed by a Chamoru sense of place that promotes a cogent challenge to militarization” (5, emphasis in original), Puerto Rican nationalists’ decolonial rhetorics were most visible in the twenty-first century struggle against U.S. militarization of Vieques. References to revolutionary leaders like Lolita Lebrón allowed them to hail a long history of anticolonial activism that is significant to environmental justice movements still today.

Almost twenty years after the U.S. Navy was ordered to stop utilizing the municipal island town of Vieques as target practice, in 2019, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez successfully passed a resolution in the U.S. House of Representatives to allocate funding for safer clean-up of live ammunition still laying around (Acevedo). Moreover, besides the environmental contamination affecting residents of Vieques, they now face a wave of gentrification, or as Vieques activist Myrna Veda Pagan Gómez put it, a “tsunami of gentrification” (Bayne and Dieppa). This, of course, is a result of the previously referenced shock doctrine, or, more specific to Puerto Rico, what Yarimar Bonilla refers to as the coloniality of disaster (“Coloniality of Disaster”). Therefore, decolonial rhetoric is still a necessary component of environmental justice struggles in Puerto Rico.

As José Atiles-Osorio suggests,

The extensive tradition of anticolonial struggle has shown that liberation in the biopolitical domain is just as important as liberation in the geopolitical domain. Thus, it is only natural that the desire for emancipation should transcend the political and become biopolitical and/or involve investment in physical, environmental, epistemological, cultural and moral emancipation. (9)

In this essay I have offered a few examples of the ways in which cultural and moral emancipation efforts intersect with environmentally just projects, providing much needed models for future movements. In fact, it can be argued that many of these are inseparable, as a decolonial approach to environmental justice would already account for physical, political, moral, and of course, cultural emancipation.

As part of my decolonial approach to environmental justice rhetoric, a transnational perspective on the intertwined nature of climate change, capital, and colonialism demonstrates that while there are local particularities that need to be accounted for in rhetorical histories, there should also be a consideration of the ways in which capital and colonial power travel. For instance, just as the coal ash company AES announced that it was moving its coal ash repository out of Guayama, Puerto Rico, which may have felt like a victory for the majority-women led movement, they discovered that it was moving to St. Cloud in Osceola County, Florida, “the second fastest-growing Puerto Rican community in the country” (Calma). Similarly, once the U.S. “Southern Command was removed from Vieques, Puerto Rico, and re-established in San Antonio, Texas, in 2006, the Secure Fence Act was fully operational” (García Tamez 302). In other words, the largest pollutants in colonial territories such as fossil fuel dependent energy sources rely on similar strategies as the military industrial complex—to set up in yet another context of vulnerable communities.

It is relevant, then, to account for the ways in which race, ethnicity, and gender are featured in environmental struggles (Pulido) especially in settler contexts (Whyte; Zaragocin). To close, I expand on the ways in which activist communities and scholar-activists engage in locally specific and transnational considerations of work that aims to counter climate change and coloniality.

Most significant for rhetorical studies, in the work of Catalina de Onís we can find stories about university/community partnerships that build coalitions that create opportunities for disadvantaged members of the communities most affected by environmental exploitation—a decolonial environmental justice effort. This partnership resulted in a renewable energy initiative they called Coquí Solar. According to de Onís, “Coquí Solar offers a grassroots example of delinking, another promising effort for constructing alternative ways of being and knowing” (“Fueling and Delinking” 553) but it also includes a partnership with affiliation to the University of Puerto Rico initiatives on the ground there. Similarly, anthropologist Hilda Lloréns has worked to document environmental injustice in the southeastern town of Salinas, connecting contamination to the establishment of industrialization projects in the second half of the twentieth century—efforts I delineated above. Moreover, Lloréns and her co-author, Ruth Santiago, note that “the heavily Afro-Caribbean region’s historically high levels of poverty have only increased. Today, 54 % of the region lives in poverty” (399). Still, “women of the community are at the forefront of the struggle against environmental degradation and catastrophe” (398). Both de Onís and Lloréns are academics established in universities located in the contiguous United States, which suggests that they have been able to maintain and establish relationships with local activists and community leaders—not a top down or detached rhetorical analysis, but a horizontal, place-based, coalition: a decolonial approach to environmental justice.

In short, de Onís and Lloréns’ scholarship focuses on supporting environmental justice work driven by decolonization efforts. Whether through an attention to energy, anti-militarism, occupying or marching in the streets, or by extending a Puerto Rican voice that is not solely focused on documenting tragedy for visibility’s sake, these efforts should be accounted for in reference to rhetorics of climate justice and environmental justice. Given the brief rhetorical history delineated above, and accounting for DiaspoRican scholarly and activist communities working to counter climate change, attending to Puerto Rican efforts towards environmental justice should extend beyond the moment of a hurricane. As scholar-activists we should not let climate chaos be the catalyst for change. By then it’s too late.

[1] Presentism is a philosophical perspective that negates the existence of the future, and the past (Ingram and Tallant). I draw from this perspective to argue against the act of judging or addressing a contemporary situation without careful contextualization (temporal, spatial, and/or other).

[2] My dissertation is an exploration of rhetorics of defiance against U.S. empire by Puerto Rican nationalist revolutionary woman, Lolita Lebrón, detailing twentieth century activisms throughout the diaspora (Soto Vega). More closely related to hurricane management, “Puerto Rico Weathers the Storm: Autogestión as a Coalitional Counter-Praxis of Survival” details the work that artist-activist collective Vueltabajo Teatro have engaged in before and after Hurricane Maria.

[3] Another important nationalist figure that made his way to Vieques was her comrade, Rafael Cancel Miranda. As a respected voice in the pro-independence/nationalist movement, Cancel Miranda has been featured in Voices from Puerto Rico Post-Hurricane María, a collection of short stories about Hurricane María edited by Iris Morales—a former New York Young Lord and established activist. In his entry, “Before and After María” he explains how “Puerto Rico was already in crisis” due to colonial debt and exploitation, impoverishment and military obligations (Cancel Miranda 75).

Acevedo, Nicole. “AOC Proposal calls for environmentally safer Military Cleanup Efforts in Vieques, Puerto Rico” NBCNews, July 12, 2019. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/aoc-proposal-calls-environmentally-safer-military-cleanup-efforts-vieques-puerto-n1029351

Atiles-Osoria, José M. “Environmental Colonialism, Criminalization and Resistance: Puerto Rican Mobilizations for Environmental Justice in the 21st Century.” RCCS Annual Review: A Selection from the Portuguese Journal Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, vol. 6, 2014, pp. 3-21.

Ayala, César J., and Rafael Bernabe. Puerto Rico in the American century: A History Since 1898. Univ of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Baca, Damián and Romeo García, eds. Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise: Contested Modernities, Decolonial Visions. NCTE, 2019.

Backiel, Linda. “The People of Vieques, Puerto Rico vs. the United States Navy.” Monthly Review, vol. 54, no. 9, 2003, pp. 1-13.

Bade, Gavin. “Puerto Rico Governor Signs 100% Renewable Energy Mandate” UtilityDive, April 12, 2019. https://www.utilitydive.com/news/puerto-rico-governor-signs-100-renewable-energy-mandate/552614/

Bayne, Martha and Isabel Sophia Dieppa. “Puerto Rico’s Vieques Island Ousted the US Navy. Now the Fight’s Against Airbnb.” The World, July 16, 2019. https://www.pri.org/stories/2019-07-16/puerto-rico-s-vieques-island-ousted-us-navy-now-fight-s-against-airbnb

Berman Santana, Déborah. “Colonialism, Resistance, & the Search for Alternatives: The Environmental Movement in Puerto Rico.” Race, Poverty & the Environment, vol. 4, no. 3, 1993, pp. 3-5.

---. Kicking Off the Bootstraps: Environment, Development, and Community Power in Puerto Rico. University of Arizona Press, 1996.

Bonilla, Yarimar. “For Investors, Puerto Rico Is a Fantasy Blank Slate: How Tech companies and Private Capital Are Poised to Reshape the US Colony.” The Nation. February 28, 2018. https://www.thenation.com/article/for-investors-puerto-rico-is-a-fantasy-blank-slate/

---. “The Coloniality of Disaster: Race, Empire, and the Temporal Logics of Emergency in Puerto Rico, USA.” Political Geography, vol. 78, 2020, pp. 1-12.

Briggs, Laura. Reproducing empire: Race, Sex, Science, and US Imperialism in Puerto Rico. Univ of California Press, 2002.

Calma, Justine. “Puerto Rico Got Rid of Its Coal Ash Pits. Now the Company Responsible is Moving them to Florida.” MotherJones. May 21, 2019. https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2019/05/puerto-rico-got-rid-of-its-coal-ash-pits-now-the-company-responsible-is-moving-them-to-florida/

Cancel Miranda, Rafael. “Before and After María” in Voices from Puerto Rico Post-Hurricane María, edited by Iris Morales. Red Sugarcane Press, 2019, pp. 75-76.

Caro González, Leysa. “Adjuntas Estrenará la Primera Red Comunitaria de Generación y Distribución de Energía.” El Nuevo Día. April 21, 2019. https://www.elnuevodia.com/noticias/locales/nota/adjuntasestrenaralaprimeraredcomunitariadegeneracionydistribuciondeenergia-2489304/

Combahee River Collective. "A Black Feminist Statement." Women's Studies Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 3-4, 2014, pp. 271-280.

de Onís, Catalina M. “Energy Colonialism Powers the Ongoing Unnatural Disaster in Puerto Rico.” Frontiers in Communication, vol. 3, no. 2, 2018, pp. 1-5.

--- “Fueling and delinking from energy coloniality in Puerto Rico.” Journal of Applied Communication Research, vol. 46, no. 5, 2018, pp. 535-560.

Dingo, Rebecca. Networking Arguments: Rhetoric, Transnational Feminism, and Public Policy Writing. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Dinzey-Flores, Zaire Z. “The Development Paradox: A Century of Inconsistent Development Plans Has Left Puerto Rico In a Perpetual State of Vulnerability.” NACLA Report on the Americas, vol. 50, no. 2, 2018, pp. 163-169.

Ellsmoor, James. “Puerto Rico Has Just Passed Its Own Green New Deal.” Forbes. March 25, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesellsmoor/2019/03/25/puerto-rico-has-just-passed-its-own-green-new-deal/#67bc7cf28fb0

Embedded. “After the Storm.” NPR, February 21, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/02/20/696495334/after-the-storm?fbclid=IwAR0JFk2LI8NHW5IGK0SRaOHl8nlzXDzzFuYbQMFfFdeHCA3f2dph7Z-RGa0

Endres, Danielle. "Environmental Criticism." Western Journal of Communication, vol. 84, no. 3, 2020, pp. 314-331.

García López, Gustavo A., Irina Velicu, and Giacomo D’Alisa. “Performing counter-hegemonic common (s) senses: rearticulating democracy, community and forests in Puerto Rico.” Capitalism Nature Socialism, vol. 28, no. 3, 2017, pp. 88-107.

García Tamez, Margo. “‘Our Way of Life Is Our Resistance’: Indigenous Women and Anti-Imperialist Challenges to Militarization along the US-Mexico Border.” Invisible Battlegrounds: Feminist Resistance in the Global Age of War and Imperialism,” special issue, Works and Days, vol. 57, no. 58, 2011, pp. 281-318.

Haas, Angela M. “Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: A Case Study of Decolonial Technical Communication Theory, Methodology, and Pedagogy.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 26, no. 3, 2012, pp. 277-310.

Hesford, Wendy. Spectacular Rhetorics: Human Rights Visions, Recognitions, Feminisms. Duke University Press, 2011.

Immerwahr, Daniel. How to Hide an Empire: A Short History of the Greater United States. Random House, 2019.

Ingram, David and Jonathan Tallant, “Presentism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/presentism/

Klein, Naomi. The Battle for Paradise: Puerto Rico Takes on the Disaster Capitalists. Haymarket Books, 2018. Audiobook.

Klein, Naomi. “A Message from The Future with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.” The Intercept. April 17, 2019. https://theintercept.com/2019/04/17/green-new-deal-short-film-alexandria-ocasio-cortez/

Lloréns, Hilda, and Ruth Santiago. “Women Lead Puerto Rico’s Recovery” NACLA Report on the Americas, vol. 50, no. 4, 2018, pp. 398-403.

Mock, Brentin. “No, Puerto Rico’s New Climate-Change Law Is Not A ‘Green New Deal.’” CityLab. April 22, 2019. https://www.citylab.com/environment/2019/04/puerto-rico-hurricane-maria-renewable-energy-green-new-deal/587311/

Na’puti, Tiara R. “Archipelagic rhetoric: remapping the Marianas and challenging militarization from “A Stirring Place”.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 4-25.

Perry, David M. “‘There are No Natural Disasters’: A Conversation with Jacob Remes.” PSMag. October 2, 2017. https://psmag.com/economics/there-are-no-natural-disasters

Powell, Malea. “Rhetorics of Survivance: How American Indians Use Writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 53, no. 3, 2002, pp. 396-434.

Pulido, Laura. “Geographies of Race and Ethnicity II: Environmental Racism, Racial Capitalism and State-Sanctioned Violence.” Progress in Human Geography, vol. 41, no. 4, 2017, pp. 524-533.

Reichard, Raquel. “Report Finds Puerto Rico Is Affected by Climate Change More Than Anywhere Else in The World” Remezcla, December 4, 2019. https://remezcla.com/culture/report-puerto-rico-most-affected-climate-change/

Ruiz, Iris D., and Raúl Sánchez, eds. Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition Studies: New Latinx Keywords for Theory and Pedagogy. Springer, 2016.

Sackey, Donnie Johnson. “An Environmental Justice Paradigm for Technical Communication” in Key Theoretical Frameworks: Teaching Technical Communication in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Michelle F. Eble and Angela M. Haas. Utah University Press, 2018, pp. 138.

Schell, Eileen E. “Transnational Environmental Justice Rhetorics and the Green Belt Movement: Wangari Muta Maathai's Ecological Rhetorics and Literacies.” JAC, vol. 53, no. ¾, 2013, pp. 585-613.

Solis, Maria. “Coronavirus is the Perfect Disaster for Disaster Capitalism.” Vice, March 13, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/5dmqyk/naomi-klein-interview-on-coronavirus-and-disaster-capitalism-shock-doctrine

Soto Vega, Karrieann. “Puerto Rico Weathers the Storm: Autogestión as a Coalitional Counter-Praxis of Survival.” feral feminisms, vol. 9, 2019, pp. 39-55.

---. Rhetorics of Defiance: Gender, Colonialism, and Lolita Lebrón’s Struggle for Sovereignty. 2018. Syracuse University. Dissertation. ProQuest.

Smith, Neil. “There’s No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster.” Understanding Katrina: Perspectives from the Social Sciences. June 11, 2006. http://understandingkatrina.ssrc.org/Smith/

United Nations. “Climate Justice – United Nations Sustainable Development.” United Nations, 31 May 2019, www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/climate-justice/.

Villanueva, Victor. Bootstraps: From an American Academic of Color. National Council of Teachers of English, 1993.

Wanzer, Darrel Allan. “Delinking rhetoric, or revisiting McGee's fragmentation thesis through decoloniality.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs, vol. 15, no. 4, 2012, pp. 647-657.

Weiss, Laura, Marisol Lebrón, and Michelle Chase. “Eye of the storm: Colonialism, capitalism, and climate in the Caribbean.” NACLA Report on the Americas, vol. 50, no. 2, 2018, pp. 109-111.

Whyte, Kyle. “Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice.” Environment and Society, vol. 9, no. 1, 2018, pp. 125-144.

Zaragocin, Sofia. "Gendered Geographies of Elimination: Decolonial Feminist Geographies in Latin American Settler Contexts." Antipode, vol. 51, no.1, 2019, pp. 373-392.