Stephanie Mahnke, Utah Valley University

(Published Sept. 17, 2020)

As a Filipina who had just moved from the heavily Filipinx-populated West Coast, I began my search for a Filipinx community in Michigan confident it would only be a matter of time before I’d find a Filipinx restaurant or business, which would then point to an ethnic enclave. Several months went by, and I was still searching. One of my last resorts was to follow signs on the city landscape hinting to traces of Filipinx presence. Aside from a sign that read “Philippine St.” marking the quiet road that housed the Philippine American Cultural Center of Michigan in Southfield, there were no public street markers, ads, images, or symbols indicating a Filipinx presence, even in the newly designated Chinatown. Eventually, I found myself in a Detroit parking lot outside an arts building that housed the “Manila Bay Café.” Unfortunately, the Manila Bay Café revealed itself to be an open mic event with no affiliation to the Philippines except a rumor that the founder was married to a Filipino. As I walked disappointedly back to my car, I was struck by a defaced mural of Vincent Chin alongside other ethnic figures. Noting I was just a few blocks from the newly gentrified Midtown area where Chinatown used to be, I came to the realization the Asian and Pacific Islander American (APIA) community was here, but the rhetoric of their physical markers seemed to tell a story of a struggling communal presence in public spaces.

At stake in the mis/nonrepresentation of communities, such as the Filipinx community, is a disruption of sustained cultural practices and values as well as a means of community advocacy and negotiation of resources. Previous research investigating the connection between the APIA community and their use of urban space has established a strong link between community advocacy and material emphasis (Bonus; Kim; Liu & Geron). Within the American public sphere, claims to space have served as relevant tactics for counteracting commercially monopolized spaces, but these claims assume equitable right to public participation and the shaping of the public sphere, which ignores the restricted nature of the public sphere. For instance, embodied and physical representations of ethnic identity and voice in city centers have been a constant strategy in today’s political climate. Black Lives Matter, a Day without Immigrants, and the Million Woman March filled specific spaces as political statement: emptying kiosks and commercial buildings as well as displaying and projecting signs as a means of countering Trump-era assertions of what an American citizen “looks” like and what rights are implicit in the more inclusive definition. The onset of 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent anti-Asian racism circulated narratives and national imaginaries of APIA identity that have further reinforced this diverse group’s identity as both foreign and domestic.

Further, fragmentation of the public sphere and the struggle for a democratized space highlight the erosion of ethnic spaces by urban development’s privileging of privatized, state, or market-driven interests (Delaney; Warner; Lloyd). Instead of what Habermas envisioned as a collective, consensual site of citizens with homogenous public concerns, the public sphere has been conceptualized as a product of a multiplicity of interrelations (Massey), and even a contentious site for negotiating public values and identity (Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel; Watson). Though this would imply a democratized space for segments of citizens to stake claims, hegemonic powers have tended to impose conditions for entry within the shifting and increasingly privatized constructions of the public. As a result, the exclusion or struggle of certain groups to gain entry, access, or voice into the public sphere has been an ongoing reality.

Although APIA space and place has been studied before in terms of identity and economic development, exploring patterns of APIA settlement and globalization (Li; Zhou, Tseng, and Kim), settlement and ethnic identification (Laux and Thieme; Bonus), and place-making and cultural practice/community (Bao; Kim), few have specifically focused on the rhetoricity of their spatial strategies as a means of public address. Even fewer have explored the relative and fluctuating conditions APIA groups must follow to enter public discourse within specific spaces. Scholars in the field of rhetoric have explored the innovative ways in which APIA groups have crafted rhetorical strategies in response to social and political contexts, particularly identifying the ongoing tension between APIA identities and the national imaginaries. Further, many of these rhetorical strategies emphasize the fraught relationship between standardized literacy and APIA identity in terms of citizenship (See: Young; Hoang). Some of these documented rhetorical strategies of resistance and identity-making have encompassed video (Ong; Pham), drawings (Wheeler), digital media (Pham and Ono; Cheung and Ono), sonic/aural forms (Sano-Franchini), and even stage comedy (Meyer) amidst a background of limiting national and transnational narratives. The essays in Mao and Young’s seminal Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric boasted the call to see APIA rhetoric beyond traditional forms of literacy and language to a process of knowledge-making that is localized, situated, and subject to temporal-spatial logics and forms

Although cultural rhetorics has spent some focus on the specific role of place/space and the rhetorical acts of place-making by cultural groups, there remains limited discussion of how material space is read alongside APIA rhetorical strategies to revise imagined geographies, particularly how such strategies are consumed and transformed by public conditioning. To add to studies of diverse forms of APIA rhetorical resistance and examine points of engagement between spatial logics and national identity, I suggest a strategy for reading cultural material claims to space and highlight the ways such readings can inform us of how cultural groups are conditioned for entry into public dialogues. A lens on material spaces particularly illuminates public negotiations surrounding local identity and rights implicitly tied to notions of territory. As minoritized voices in the public sphere, APIA groups have experienced limited agency in public participation and recognized voicing of political issues in Michigan. Much like the anecdote of my search for a Filipinx American community, Detroit’s APIA’s proved a scattered presence based on what could be found from their material traces. These material traces (or lack of) can be read as their own texts, ones which have the potential to illuminate the nature of a group’s entry or participation in public discourse.

In the following, I propose a theoretical framework for analyzing the rhetorics of spatio-cultural uptake, an approach to reading spatial claims from cultural groups and its rhetorical potential for public address, which underscores concepts of territoriality and spatial networks alongside theories of public attention and recognition. Using Lynn A. Staehali, Don Mitchell, and Caroline R. Nagel’s Regimes of Publicity, I explain how spatial claims may be recognized by publics and what factors contribute to their mis/nonrecognition. I apply these ideas to an analysis of two examples of the APIA community’s attempt at public address through their display of two murals in Detroit. Finally, the murals’ analyses are followed by a discussion of how material readings of space may illuminate the conditions which influence a group’s degree of access to the public sphere and nature of participation. Since the public sphere is imagined and continuously shifting, I don’t intend to provide an empirical or definitive analysis of how a group gains entry into the public sphere. Instead, I explore how the proposed framework may be illuminating through its application in one case study—in this instance, Detroit APIAs’ struggling efforts for presence and public address, and the complex factors that contribute to the recognition of spatial-material claims.

Asian and Pacific Islander American Place-Making in the Midwest

The story of APIAs in the Midwest is one of interrupted spaces and fragmented communities. Detroit’s APIA community has been displaced by zoning laws, prejudice, and urban planning for over one hundred years. This has contributed to movements such as the upheaval, transfer, and eventual death of an entire Chinatown; the relocation to the suburbs or other states; and the displacements to low-income, crime-infested areas like Cass Corridor and the Eastside District—only to be pushed out again during phases of redevelopment. These transferences have provided a challenge for sustainable APIA communities, making their presence—despite its diversity and numbers—struggle to be representative in public spaces.

Considered the region of Asian American “unsettlements,” the Midwest starkly contrasts states such as Hawai‘i and California, which are known for high APIA populations and recognizable spaces.[1] For example, two of the largest relocation movements in the United States involved the forced displacement of Asian Americans—the Japanese community in the 1940s and the Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees of 1975—which scattered these groups across the Midwest to disrupt pre-war ties and prevent the formation of ethnic enclaves (Kim; Bily). The pattern of dispersal continues today with the added aid of Detroit’s urban development, making it difficult to sustain APIA ethnic space (Chan, Kim, and Gauri; Hunter). In a study by Barbara Kim, Asian Americans in Michigan exhibited less discernable ethnic enclaves than their western geographic counterparts, and instead, demonstrated dispersed patterns of (largely heterogeneous) ethnic space. Marking the interplay between material spaces and political participation, she found that to produce a concerted response to their racialized group’s political issues, Michigan’s Asian Americans were, to a greater degree, operating within multicultural geographic boundaries with other co-ethnics rather than within their individual APIA ethnic groups.[2] Kim revises Vo and Bonus’ bicoastal model of formal ethnic enclaves by echoing Ling’s Midwestern cultural community model wherein dispersed Asian American groups are found to engage in the heterogeneity of co-ethnic communities (Kim 86; Vo and Bonus; Ling). Pan-Asian solidarity has been a necessity, as Kim’s participant explains, because “nobody else is going to stick up for us” (qtd. in Kim 87). In other words, APIA public participation in Midwestern states such as Michigan for their groups’ political interests is more likely to occur through multicultural collaboration rather than from within their own racialized group.

The current literature’s perception of Midwestern APIA’s process of place-making and community advocacy provides an interesting backdrop upon which to apply a contemporary material reading of an APIA place-making act. The material analysis of APIA’s spatial rhetoric reveals signs of conditioning for cultural representation, particularly that (1) heterogeneity may not be so much wishfully designed as it is necessary, (2) APIA political claims must delicately balance historical narratives of APIA social injustice with the shifting local demographics resulting from numerous displacements, and (3) property ownership is a significant factor for public participation. This pattern of nonrecognition echoes the Midwest’s historical pattern of neutralizing Asian American difference, limiting their distinction as racialized agents within the public. Material analysis may help us understand the nature of such mis/nonrecognition.

Theorizing Spatial Publicity

To investigate the APIA community’s practices for lodging claims for recognition, acceptance, and inclusion in the public sphere through physical markers, a theoretical framework must consider analysis of material claims to space in relation to public attention. The concept of Regimes of Publicity provides one framework for deciphering how material claims function within the system of laws, practices, and relations that condition qualities of a public. Developed by Staehali, Mitchell, and Nagel, Regimes of Publicity assumes not everyone has access and voice within a public space to be representative within the public sphere. A number of socially agreed upon rules already influence economies of public attention that Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel outline in three sets of relationships: (1) community and social norms refer to some sense of commonality with the public through aligned concern(s) or history. This commonality and ability to interact in interpretable ways influences the chances of a message’s uptake from strangers willing to engage in discussion over the message. (2) Legitimacy refers to the idea that claims must be seen as normal, unremarkable, and legitimate by already existent notions of publicity. This may be difficult for groups vying for public access because they’re already viewed as illegitimate, so many strategies may include demonstrating how practices may be seen as legitimate in other senses. (3) Relations of property refer to the relationships that exist in and through place which regulate who can make claims in that area. Although Staehali, Mitchell, and Nagel emphasize the rights of a locale as influenced by property ownership, those rights are “also the set of relationships and rights that make property meaningful as a form of wealth, as a resource in building places and structuring activities, and as imbued with power” (643). This last point draws connections with networks of spatiality and can perhaps be seen as a material form of semiotics that works to uphold certain public narratives—or in the authors’ case, what is already regulated by property ownership.

Regimes of Publicity and their application on political geography draw from a number of key theorists. The concept underscores the discursive power and intricacies of public recognition. “Politics of recognition,” coined by Charles Taylor, highlights how forms of difference fundamentally affect how political agents are recognized and situated in the public sphere, influencing their capacity for public participation and the sorts of goals these groups work to achieve. According to Taylor, identity is partly shaped by recognition, misrecognition, and nonrecognition from others. In the case of APIAs, this “nonrecognition or misrecognitions can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being” (Taylor 25). Recognizing non/misrecognition as more than just a barrier to identity development, Fraser critically extends Taylor’s politics of recognition to point to the notion that some groups are denied equal “peer” status in social interaction as a result of institutionalized patterns of cultural value. To investigate politics of recognition is, then, to investigate how discursive representations of identities are assigned lesser value by publics. Thus, the discourse of recognition and its subsequent politics of equal dignity is a driving factor in groups’ positioning in the polity and can dictate forms of access and rights within the public sphere.[3] By considering the chances of a message’s uptake by strangers, Regimes of Publicity works to highlight such economies of recognition by laying out the producer-public relationships which influence recognition and acceptance.

Along with its attention to economies of public attention and recognition, Regimes of Publicity also show conceptual similarity with a Foucauldian framework for the production and control of discourse/statements, allowing us parallel insight into how the discourse of material claims function and are identified within discourses of recognition. According to Foucault, discourse is regulated by three reinforcing practices: (1) internal delimitation of statement’s materiality (where and when it was produced and from what position); (2) external delimitation (exclusionary limits imposed by surrounding statements/neighboring concepts); and (3) conditions of deployment (the conditions under which one can utter truth). Regimes of Publicity underline such external societal conditions that control speech acts through the concepts of legitimacy and public “norms.” Even further, exclusionary limits as dictated by surrounding statements and neighboring concepts refer specifically to Regimes of Publicity’s idea of Relations of Property (what claims exist and continue to limit discourse in a given locale). In this way, a consideration of surrounding material claims considers the link between claims of territoriality and their sustainment through spatial networks. Just as Foucault asserts that power needs constant maintenance to remain active, so too do assertions of territory need repetitive and parallel networks of visible (material) artifacts to stabilize claims on space. Fairly stabilized territories require what rhetoricians Danielle Endres and Samantha Senda-Cook allude to as repeated reconstructions over time, or what other researchers have suggested as a continually produced, processual operations that work to produce and stabilize territorialization (Karrholm; Brighenti).

Various place/space studies have attempted to articulate the link between visibility and territoriality as determinants to the public sphere amongst other marginal groups. Wells, applying Lefebvre’s concept of representations of space as framework, articulates the importance of material-visual rhetorics of space from “below” to not only be indicative of lived spatial practice within the city’s sedimented power relations, but a necessary form of undoing the “spectacle” of a privatized or government-controlled landscape. As an on the ground spatial practice invented in conjunction with national imaginations of minority identities, minority groups have used murals to combat city bureaucracy as well as transform public spaces into a constructed “homeland” while simultaneously defining cultural and communal identity. For instance, Margaret R. LaWare’s analysis of Chicano murals, invented during the Chicano Civil Rights movement and the “people’s” murals of the 70s, demonstrates how the community’s murals functioned together to forward arguments of distinct cultural identity while also resisting outside control of its neighborhood. Within minority communities, the rhetorical impact on community building is clear, though the nature of broader public uptake has needed further investigation. Andrea M. Brighenti’s study on graffiti writing as a territorial discourse practice theorizes graffiti walls as a limited socio-spatial field of visibility that commands public attention and contribution to the public sphere. Spending most of her time theorizing the visible potential of walls as boundaries or thresholds of public space alongside internal delimitations of discourse conditions amongst other graffiti writers, Brighenti’s study produces an intimate look at the potential of public recognition and material networks of public address, however, with limited exploration of discourse regulation as carried out by public stakeholders. What comes closer is Arlene Davila’s study of New York’s competing commercial and Latino/a/x marketing efforts which concentrates on public uptake of material claims, citing the increasing threat of gentrification against material-visual markers promoting Latinidad and the community’s political concerns. In her study, she focuses on how larger webs of material street markers gauge accepted public opinion in Latino/a neighborhood strongholds. Her analysis of concentrated areas and specific stakeholders highlights similar notions of material alignment with community values, legitimacy, and relations to property (though not in these explicit terms), providing insights into a specific ethnic group which I believe can be transferred into analysis of APIA material claims through a framework that combines insight into spatial processes and visual impact.

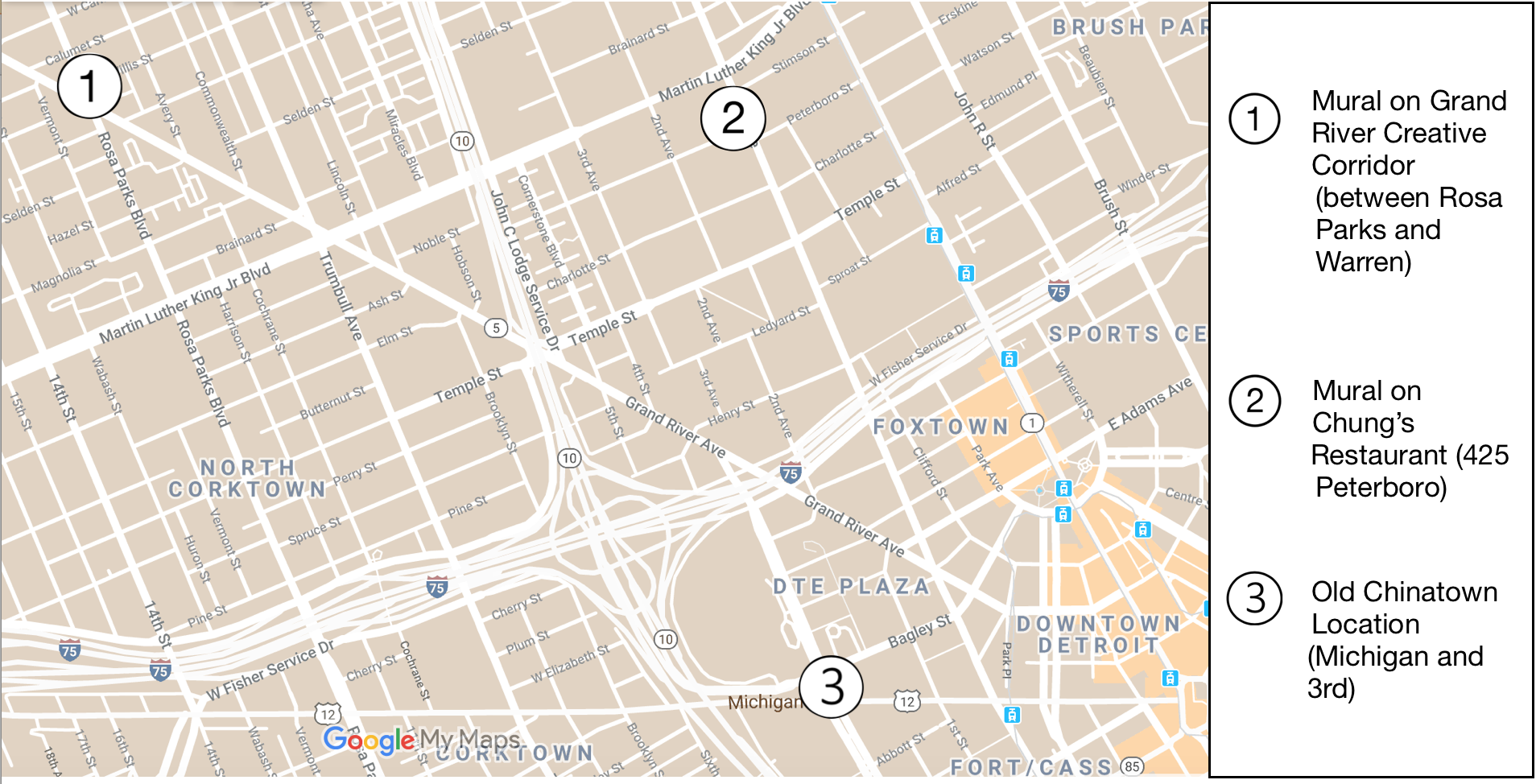

Detroit’s APIA Markers

The methods I use in this study involve analysis of intended mural meanings by APIA stakeholders and its subsequent uptake by publics. I analyze Detroit’s only Vincent Chin murals in Chinatown and at Grand River Creative Corridor as material fixtures in urban areas that allow an open and visible threshold in which general publics can interact with the APIA-represented communities. These two murals are prime examples for study as they provide somewhat stable variables in terms of the Vincent Chin theme—arguably the most APIA-defining event in Detroit (Rahal; Kim)—and spatio-temporal frame as they were both taken down in Detroit locales in 2014 and 2016, respectively. The mural in the most recently designated Chinatown area was also the first of its kind from the APIA community as an attempt to revitalize and establish belonging in the area. The murals’ intended meanings and public reactions were gathered from APIA groups’ public documents, quotes from mural participants, news sources, and social network testimonies. To demonstrate how Regimes of Publicity, with its three regulatory practices of internal delimitation, external delimitation, and conditions of deployment, can be applied to decipher factors impacting social uptake, I highlight how we might think about a small set of explicit claims from each of the murals and open discussion of considerable influences to the murals’ strategies and challenges towards public address.

Vincent Chin Mural on Peterboro

The first Vincent Chin mural sat amongst remnants of Detroit’s Chinatown on Peterboro Street and Cass Avenue between the years 2003 and 2016. In a collaboration between the Detroit Chinatown Revitalization Group, the Bogg Center’s Detroit Summer, and the On Leong Chinese Welfare Association, the Vincent Chin mural was erected on the north wall of the building that once housed the famous Chung’s restaurant. The mural kept company with other APIA material markers such as a kiosk welcoming passersby to Chinatown, the Association of Chinese Americans Drop-In Center (sharing Chung’s building), and the closed Shanghai Café (see fig. 1). Together these material markers show withering signs of Chinatown’s attempt to attract the same numbers and level of activity as its previous location on Michigan Avenue and Third Street.[4] The mural was taken down on November 4, 2016, as a result of new property ownership, but the mural’s message had already endured dwindling potential as the area has gradually fallen victim to urban redevelopment plans (Wasacz; Chu; Harris). The mural’s removal symbolically sealed the fate of the dying Chinatown, despite the APIA community’s multiple revitalization efforts. Mural participant, poet, and educator Aurora Harris recalled leading the Detroit Asian Youth tours of Chinatown to teach the public her “oral history, the importance of history and cultural preservation, [the community’s] efforts to revitalize the area, the garden of indigenous Asian plants and vegetables planted in the lot next to the mural, and how Asian enclaves form and are destroyed due to systemic racism and hate crimes.” After the mural was removed, the tours stopped, and the APIA community’s last gathering in the area took the form of a “Peace and Justice” drum circle as they removed the mural panel by panel. The mural now sits in the Allied Media Office in Detroit (Harris).

Fig. 1. Map of Vincent Chin mural location. Map Source: Google Maps. Images: Wasacz.

Facing Peterboro Street, the mural served as a political statement against APIA hate crimes and the inclusion of APIAs in the Detroit community and history (Wey; Wasacz; Detroit Chinatown Revitalization Group [DCRG]). Through its textual images, the Vincent Chin mural’s claim was one of “Justice, Equity, and Diversity” as well as a promise for the creation of a once-again booming Chinatown with images of projected Vincent Chin Museum, and new restaurants, among other new buildings. First, the mural displayed figures relating to identity-movements that had local significance in Asian and African American civil rights: hate crime victim Vincent Chin, Asian American activist and spokesperson for American Citizens for Justice Helen Zia, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose first “I Have a Dream” speech occurred down Woodward Avenue. Further, the neighborhoods (Black Bottom, Paradise Valley, and the previous Chinatown) painted in the upper left and right of the mural are of predominantly African-American and Asian neighborhoods which were displaced to Cass Corridor following the construction of the John C. Lodge freeway. These two racial groups displayed by the mural refer explicitly to the area of Chinatown and tie the territory to the identities of two historically racial neighborhoods. Finally, the mural includes a vision for Chinatown’s future, one that mixes a post-industrial experience alongside a rich history of race relations (DCRG; Chu). The vision included new grocery stores, restaurants, specialty stores, senior and mixed-income housing, a Vincent Chin Memorial Museum, a venue for celebrations and traditional/folk celebrations, and a historical designation for the neighborhood.

Fig. 2. Vincent Chin mural on Peterboro. Source: Harris.

Despite the mural’s intentions, it failed to galvanize enough public recognition to bolster change for the struggling Chinatown. As mentioned before, other factors—such as urban redevelopment and scarcity of APIA inhabitants—play a role in the mural’s short life in the area. However, material emphasis and spatial strategy also produce and reflect inclusionary and exclusionary forces involved in the construction of place-making as public address. To begin using Regimes of Publicity as a lens for investigating the mural’s considerations and challenges toward social uptake, I start with the first relationship: the mural’s compliance to community and social norms.

Community and Social Norms

Aligned economic potential. One of the major narratives about Detroit’s Chinatown is public interest in its economic potential and/or reviving the bustling economic activity of Detroit’s previous Chinatown on Michigan and Third. The mural’s presentation of new businesses (both Asian and non-Asian), housing, tourist shops, and a museum promote APIA culture but also contribute to the economic development of the area and its inhabitants. The surrounding area had already witnessed one of the first of many business projects belonging to new redevelopment plans as early as 2005, and the mural included APIA community as inclusively contributing to this business development. By emphasizing APIA-run or themed venues, the mural also aligns itself with the established norms of the area’s Chinatown designation.

Misaligned pre-existing histories. Though the mural supports public economic concern for the area, the mural’s troubling alignment with community and social norms occurs with the designation of the displaced Asian and Black neighborhoods and implied continuance in the new Chinatown territory. By representing two neighborhood communities with specific histories of Chinatown displacement alongside Asian and Black histories of racial injustice more broadly, the mural makes a complex claim of local community and wider public norms. Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel make an important distinction between the terms “community” and “public.” Distinguishing community as “social solidarity derive[d] from sharing a preexisting history, experience, or identity,” they define the construction of the public as intrinsically requiring the discursive interaction of strangers (Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel 643). However, shared norms of publicness are often interrelated with community norms and vice versa; thus, although community and social norms may lead to social uptake from strangers and participation in construction of the public, certain feelings of publicness may also facilitate communally shared ideals. As one of the mural project’s coordinators Soh Suzuki pointed out, the mural’s representation of Asian inclusion in a predominantly Black area represents a gesture to a larger Detroit public with the inclusion of African American history and presence (Wasacz). However, it also goes against community and social norms of the area by referring to the previous Chinatown’s inhabitants who are likely not living in the Peterboro and Cass location. Put another way, though the mural aligns itself with the greater demographic of the Detroit public, it territorially asserts the place-identity of specific micro-communities that may no longer have affiliation with the new Chinatown area (the resulting dynamic of forced socio-political displacement). A different pre-existing history exists for the residents of the current Chinatown area, signaling a separate community than the neighborhoods represented in the mural.

Legitimacy

Contentious claims of displacement. Building from the representation of the displaced neighborhood, the mural’s claim may also pose issues of legitimacy, which negatively affects public uptake. Coordinator Suzuki reiterates in an interview that the mural is meant to remind the public of the troubling history of displacement of people of color (Wasacz). The contentiousness of this claim may be classified as remarkable under Regimes of Publicity, and the strategy of reasserting the neighborhoods within the new Chinatown is a territorial act of legitimacy against this continuous political struggle. Similarly, Arab immigrants in Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel’s study have used comparable legitimating tactics as presenting stories of themselves as rightful citizens within an American locale despite the continuous political push against this idea.

Uncontentious hate crime commemoration. The mural strategically presents a mix of legitimate and socially valued messages (economic development; a nod to broad area demographics) alongside remarkable claims (re-territorializing the new Chinatown for two specific neighborhoods; the wrongful displacement of POC communities). Perhaps the driving legitimating vehicle is the mural’s claim against the Vincent Chin hate crime. Through its title, publicity, and center focus, the mural forefronts the remembrance of Vincent Chin, whose wrongful death and lack of justice became a watershed moment for the APIA civil rights community. Though a deeper study could decipher whether the narrative of Vincent Chin is publicly accepted and legitimate under Detroit’s major civil rights heritage, Vincent Chin commemorations in the city broadly fit the standards of “successful” and publicly accepted commemorations according to Goshal’s considerations of public racial violence memory. In his extensive study of racial violence memory movements – with notable consideration of material commemorative structures – Goshal notes the importance of readily mobilized institutions and groups around the cause, historically accepted perceptions of the victim’s good moral standing, and ingrained notions of the incident’s importance. With yearly commemorations of the Vincent Chin hate crime by Chinese cultural groups, recognition from other APIA groups, and city/institutional support for these efforts across the decades, combined with more than ten news stories, and a relatively stable narrative of the hate crime’s injustice across celebrations and coverage, the message of Vincent Chin arguably proves to be among the mural’s publicly legitimate claims.

Relations of Property

Lack of property ownership. Regimes of Publicity’s third relationship emphasizes the importance of a cultural group’s links to property ownership to access to a public space. For example, Arab immigrants in Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel’s study were property owners and residents of Arab Town; thus, their claims of legitimacy in the area were reinforced by the rules and norms of that property and the assemblage of visual markers in Arab Town. Arguably one of the strongest factors against the mural’s social uptake involved the change in ownership of the property that showcased the mural. The On Leong Chinese Welfare Association ceded ownership of the property in 2016, and the mural was taken down as a result of the ownership change (Chu). The APIA community also had their broader concerns about the area’s gentrification. “As a community of activists, artists, and poets, we felt that removing the mural was the best thing to do because gentrification had taken place in the Cass Corridor and what was left of Chinatown,” Harris writes, “we didn't want the mural vandalized or stolen.”

Misalignment with material surroundings. Finally, though it is strategic for groups to contest and reframe norms that involve property—such as the mural’s attempt to reframe Chinatown as a bustling multiethnic arena promoting APIA business and remembrance—these reframings are often challenged by the rhetoric of material surroundings. The mural’s claim interacts and negotiates Chinatown’s space with other fields of visibility, but Peterboro-Cass intersection is only visibly marked by Detroit Bike Shop (across the street, facing the mural), the welcome to Chinatown kiosk, a red-brick walled cinema at the end of Peterboro, and signs for the On Leong Association on the mural’s building. Thus, the mural interrogates the particular public space as a space for diversity, territory of two particularly racialized neighborhoods, and economic space for prospering Asian establishments although other material markers within its field of vision negate these delineations.

Theorizing the Conditions of Spatio-Cultural Uptake

Through the lens of Regimes of Publicity, we see Chinatown’s Vincent Chin mural’s forefronting of a publicly accepted hate crime commemoration alongside contentious political concerns surrounding the displacement of POC populations and the territorial reclaiming of Chinatown. For potential social uptake, challenging conditions that contribute to recognized entry into public discourse include the APIA community’s ability to balance specific histories of social injustice with shifting local demographics and norms. The move of Chinatown to its new location repositioned representation of groups’ specific pre-existing histories within a locale that may not recognize or relate to the previously displaced neighborhoods. A second condition—and one also affected by dramatic recoveries from displacement—involves the need for significant property ownership and/or aligned surrounding material markers. Despite decades of property ownership from the On Leong Chinese Association, the mural’s message had gone unfulfilled and redevelopment plans gradually created an assemblage of contesting material markers until a change of ownership sealed the fate of the mural, its public message, and the increasingly conflicted identity of the area as a Chinatown. The mural’s partial social uptake and eventual removal mark limited public recognition and value for APIA concerns in light of a confluence of other public values. That said, it does exemplify the challenging conditions of mutually relating to a multicultural and shifting demographic as well as alignment with neighboring material concepts.

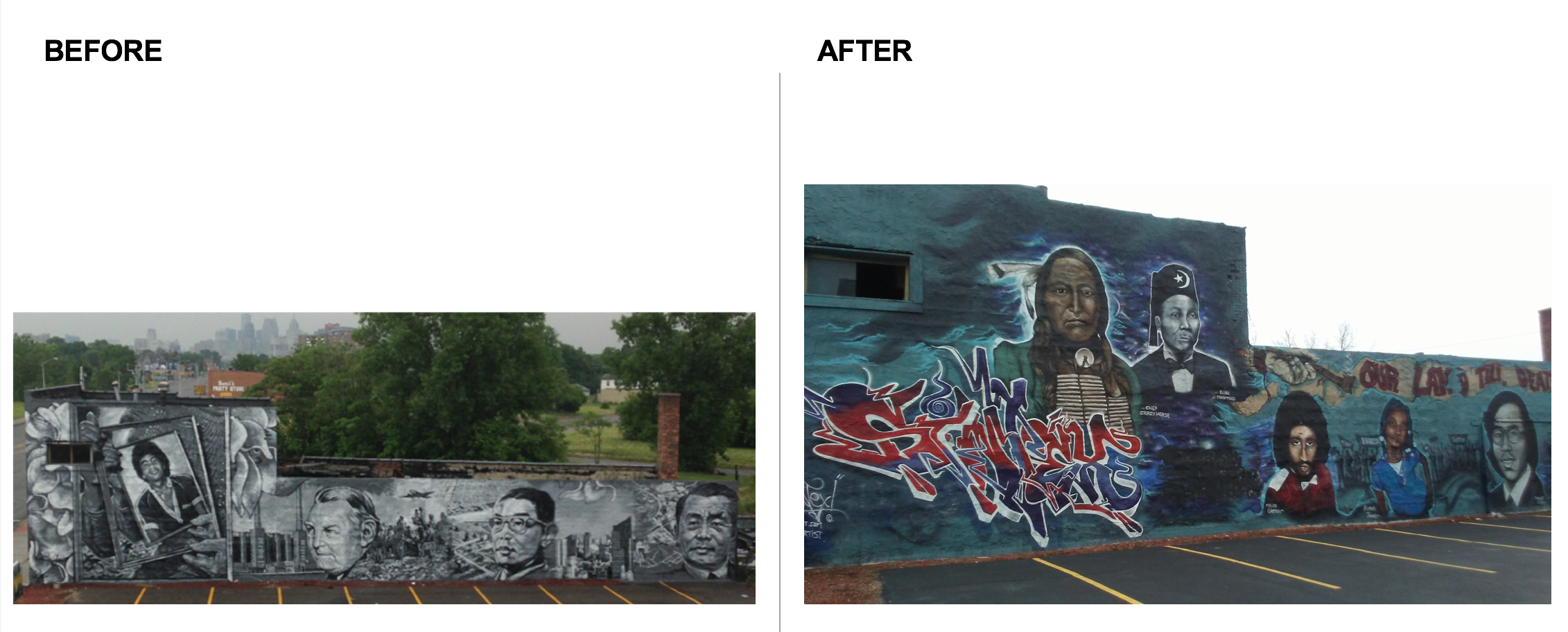

Vincent Chin Mural on Grand River

If Chinatown’s Vincent Chin mural demonstrates potential struggle with public uptake on a number of discursive/material conditions, most definitively in regards to achieving relations of property, a later attempt at a Vincent Chin mural on Grand River Avenue reveals how publicly active spatial negotiations may override and overpower APIA political claims that don’t align with local publics in particular ways. Grand River Avenues’ repeated reconstructions of the public space actively negotiate territoriality and political claims as groups vie for public attention. A rhetorical analysis of the negotiated and rewritten place-making event demonstrates how APIA claims are challenged from entering public space based on certain “correcting” conditions.

Grand River Creative Corridor is a project involving mural art to revitalize decaying buildings along the stretch of Grand River Avenue between Rosa Parks Boulevard and Warren Avenue (see fig. 3). The project initially started in 2012 with the intent to bring in local artists to create murals on fifteen buildings along the street (Sands). Though the revitalization effort was slated to end the following year, the area’s mural-making activity continued to flourish with murals totaling 100, swapping out murals every 1-3 years, and inviting local as well as outside artists into the fold. The purpose of revitalization was also married with the idea of creating a local community, and the open direction of the project’s development has produced active contestations of murals as a form of dialogue in defining the local area and community. In other words, the economies of public attention via murals in this instance have clear claims of territorialization in terms of local artists and local community identity, but as a site that’s constantly deterritorialized, it takes an interesting pulse on which claims are publicly sustained and recognized, and which removed. A large part of the public domain is negotiated through the dialogue of rewritten, replaced, and even defaced murals. Stakeholders such as local artists, building owners, and affiliative organizations have agency in what defines the community by negotiating through these mural presentations.

Fig. 3. Map of mural locations. Map source: Google Maps.

The mural receiving the most renowned defacement and rewriting was the Vincent Chin Memorial mural, created in 2014 by international artist Gaia. The mural was defaced in a matter of two months, making it the shortest-lived mural since the project’s start. The Vincent Chin Memorial mural began as Gaia’s idea after he was invited by the project’s director Derek Weaver. Gaia, touched by Chin’s story as a watershed moment in Asian American history and wanting to connect it to the globalization which spurred the racist attack (Neavling), offered the mural idea to Weaver who then sought the Chin family’s approval. Weaver was referred to American Citizens for Justice, a non-profit group organized because of Chin’s injustice and serving Michigan’s Asian Pacific Islander American communities. The group negotiated details of the mural with Gaia before the final mock-up was confirmed (Grand River). The mural depicted a portrait of young Vincent Chin with hands holding up layers of frame (see fig. 4).

Though an APIA-oriented organization signed off on the mural, it was purportedly Gaia’s “non-local identity” as an artist from Baltimore and his message that made the mural an instant target of public resistance. Street artist Sintax painted over the mural to contest Gaia and further admonishes, “This just is not just painting some bullshit ass mural about what you think my city is” (qtd. in Neavling). Though it was offered as an Asian American message and approved by a local Asian American group, the identity of the community was supposedly complicated by various implied boundaries that have been perceived and contested by the community: Chin’s relation to Highland Park, Gaia’s relation to Baltimore, to even the mural’s relation to global events. Here, APIA identity and politics are contested in terms of value and belonging with the local public. Gaia, although noting the problematics of revitalization through outside art, articulated this clash in his response: “Buffing the memory of Vincent Chin is a misplaced critique on the murals that are clashing with graffiti. Instead it comes off as a gesture against the Asian community of michigan” (qtd. in Neavling). Though Sintax’s main contention with the piece was its non-local affiliations, he uses the APIA iconography but only with the inclusion of a broader message regarding Native and African Americans. He repainted the mural to include Vincent Chin, among other Detroit figures and famous victims of brutality such as Crazy Horse (mixed African/Native ethnicity), Elijah Mohammad, Aiyana Jones, and Malice Green (DeVito). Since its 2014 “rewriting,” the modified mural and reduced APIA message continue to occupy the parking lot on Grand River today.

Fig. 4. Vincent Chin mural on Grand River Creative Corridor. Source of before photo: Gaia (http://gaiastreetart.com/Murals-and-Commissions)

Community and Social Norms

Misaligned pre-existing histories. Unlike the Vincent Chin mural on Chinatown, the original mural on Grand River pushes Asian American history to the forefront without other strategically added claims toward community and social norms (e.g. economic development, established designation of an area such as Chinatown, or a nod to the greater demographic of the area). Both the message from Sintax and the outsider status of Gaia point to public contention against the mural’s representation of local community values and norms. Locals’ opinions on both sides of the debate regarding the mural’s appropriateness in the locale litter the comment sections of Pisacane’s and Weaver’s official statements. As Weaver aptly concludes, “The defacing of the recent Vincent Chin mural … is an indicator that the community in Detroit has some work to do” (qtd. in Grand River). The mural's rewriting still includes Vincent Chin, but only by broadening the claim to include the wider Detroit public’s shared history of major ethnic figures and victims of brutality.

Legitimacy

Uncontentious hate crime commemoration. To build on the last point and the previous mural’s emphasized representation of Vincent Chin, there seems nothing remarkable about the claim and narrative involving justice and remembrance for the Asian American figure. However, the re-writing of the mural to include predominantly African American historical figures implies that it is remarkable to have this APIA political claim presented on its own. Similar to the strategy enacted in the Chinatown mural to put Chin alongside multiethnic claims, the Grand River mural was negotiated with Chin off-center and alongside other racial icons. Since Grand River Creative Corridor’s project rules are to alternate murals periodically, a single mural focusing on an APIA group’s message wouldn’t wholly conflate the local public’s identity to that of APIA groups; nonetheless, the mural’s short-lived existence and re-written narrative accommodates their material claim only with the multiethnic inclusion of other Detroit figures.

Relations of Property

Unthematic material surroundings. Relations of property are complex for this project, as the Grand River Creative Corridor’s director intended the public space to be open to various artists and locals, but he is also responsible for commissioning outsider artists to give their own rendition of Detroit iconography. Nonetheless, artists paint the murals on a rotating basis. What surrounded the passerby’s view of the rewritten Chin mural were three surrealist representations of faces on the other side of the street, and on the other end of the parking lot, a bare-walled brick art studio with only the words “art in a living context.” The surrounding material assemblage is without explicit ethnic claims but perhaps a promotion of art, neither promoting nor contesting the rewritten Chin mural (see fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Visual-material surroundings of Chin mural on Grand River Creative Corridor.

Theorizing the Conditions of Spatio-Cultural Uptake

The Grand River Vincent Chin mural provides an interesting case alongside Chinatown’s mural: to comply with community and social norms, APIA political claims must again relate to local demographics and include multiethnic claims as a means to present their own concerns. Though Sintax states the sole Vincent Chin mural was an issue of local identity and territoriality, the keeping of Vincent Chin alongside a greater narrative of African and Native American figures assigns degrees of cultural value and allows APIA inclusion but with some negotiation. To return to Ling’s cultural community model and Kim’s assertion of APIA ethnic spaces as needing pan-ethnic collaboration for political mobilization—especially when material claims are not anchored by culturally specific ethnic enclaves—APIA material claims are indeed increasingly experienced with the heterogeneity of co-ethnic claims, and consideration of the murals’ shifting discourse and social uptake reveals that co-ethnic collaboration continues to be a strategic necessity.

Conclusion

Following Rory Ong’s call that Asian American rhetoric and rhetorical practice should “account for the dialectical relationship of its habitus with western structures of domination” (27), my purpose here has been foremost to introduce a theoretical framework, a way of deducing recognition of cultural acts of public address in material spaces, or it’s spatio-cultural uptake, and secondly, to show the sorts of insights afforded when applying the framework to a specific group and locale—in our case, Asian American groups’ engagement with public discourse in Detroit, Michigan. Cultural rhetorics has certainly considered the historicity within material spaces and symbolic/social geographies, and the thematic narratives which invoke particular arrangements of space, culture, and public, but still work to build on rhetorical place/space studies through further investigation around the life and development of cultural spatial claims. If, as rhetoricians, we widen our view of cultural place-making acts to encompass its context, reception, and potential for rhetorical impact, we allow ourselves a more dynamic model of “convening publics.” Clive Barnett’s work reiterates for both humanists and geographers the essential examination of address-and-response in public discourse, reminding us that “any such address to others only comes off as a public act because of a relationship of attention between speakers and addressees that is constituted by the response of the latter” (411, emphasis added). A material analysis of cultural representation as public address offers us a glimpse into what conditions influence public attentions and ultimately the social uptake of place-making acts. Combined knowledge of the processes of territoriality, spatial networks, and public attention may inform investigations concerning the rhetorical potential of spatial claims for many groups jostling for a specific positionality in the public. As demonstrated through Detroit’s Asian American murals, this lens for viewing spatial claims not only reveals the unique contexts in which cultural groups position themselves in the public, but also the tensions which may set conditions for public recognition and acceptance of their positionality.

Other groups may take advantage of the framework’s interlinking considerations of public mis/alignment when crafting material messages, as I’ve no doubt symbolic and material patterns from similar cultural group messages circle sets of topoi that are subject and symptom to public conditioning. Such investigations into a multitude of cultural place-making events have the capacity to inform regional studies surrounding cultural groups’ public standing and how that affects the rhetoricity of their attempts at community advocacy. In this study, by applying the above heuristic to specific case studies in Detroit, the analyses demonstrate the complexity of publicity and subsequent regulatory considerations for promoting material discourse from APIA communities in the Midwest. Side by side, the two Vincent Chin murals present parallel dynamics for conceding to community, social norms, and matters of legitimacy as they attempt to promote their own political concerns. Both murals establish the strategic need for APIA claims to present with co-ethnic representation, to legitimize themselves through stricter alignment with values of the area’s local demographic, and—though limited in their cases—to take much needed advantage of relations of property and conceptually-aligned material assemblages. Further studies may extend discussion of these theoretical considerations of space and public attention in other communicative arenas where address-and-response is present. However, through an analysis of the removal and rewriting of the Chin murals, notions of publicity and material discourse help provide insight into the current conditioning of public and material space, and how that offers one angle into group struggle for entry into the public sphere.

[1] Cultural theorists have found communities with high numbers and recognizable spaces, such as those in California and Hawai‘i, to be privileged as more advanced (Wong).

[2] According to 40 interviews of Asian American Michiganders in 1998 and 99, Kim found such community formations to occur within the spatial boundaries of college campuses, churches, and temples.

[3] Taylor posited that the identity politics discussed within politics of recognition contain the inherent goal of equal recognition, which involves equal dignity or the equalization of all rights and entitlements.

[4] The 1961 urban renewal plan moved Chinatown to its Peterboro-Cass location to make space for the John C. Lodge Freeway. Most Chinese inhabitants either moved to the suburbs or, turned away from real estate because of increased post-World War II prejudice, moved out of Detroit entirely, leaving only a few hundred inhabitants by the 1980s (Chan, Kim & Guari).

Bao, Jiemin. “From Wandering to Wat: Creating a Thai Temple and Inventing New Space in the United States.” Amerasia Journal, vol. 34, no. 3, 2008, pp. 1-18.

Barnett, Clive. “Convening Publics: The Parasitical Spaces of Public Action.” The SAGE Handbook of Political Geography, edited by Kevin R. Cox, Murray Low, and Jennifer Robinson, SAGE Publications, 2008, pp. 403-417.

Bily, Cynthia A. “Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act 1975.” Immigration to the United States, Immigrationtounitedstates.org, 2015, http://immigrationtounitedstates.org/607-indochina-migration-and-refugee-assistance-act-of-1975.html.

Bonus, Rick. Locating Filipino Americans: Ethnicity and the Cultural Politics of Space. Temple University Press, 2000.

Brighenti, Andrea M. “At the Wall: Graffiti Writers, Urban Territoriality, and the Public Domain.” Space and Culture, vol. 13, no. 3, 2010, pp. 315-332.

Chan, Tai, Tukyul Andrew Kim, and Kul B. Gauri. “Three Legacy Keepers: The Vices of Chinese, Korean, and Indo-American Michiganders.” Asian Americans in Michigan: Voices from the Midwest, edited by Sook Wilkinson and Victor Jew, Wayne State University Press, 2015, pp. 131-141.

Cheung, Alison Yeh and Kent A. Ono. “Asian American ‘Hipster’ Rhetoric: The Digital Media Rhetoric of the Fung Brothers.” Enculturation, no. 27, 2018, http://enculturation.net/asian-american-hipster-rhetoric

Chu, Deborah. “Visiting Murals and Healing the Past of Racial Injustice in Divided Detroit.” Murals and Tourism: Heritage, Politics, and Identity, edited by Jonathan Skinner and Lee Joliffe, 2017, pp. 165-179.

Davila, Arlene. “The Marketable Neighborhood.” MediaSpace: Place, Scale, and Culture in a Media Age, edited by Nick Couldry and Anna McCarthy, Routledge, 2004, pp. 95-113.

Delany, Samuel R. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. New York University Press, 1999.

Detroit Chinatown Revitalization Group. “mural-brochure.” 2003.

Endres, Danielle, and Samantha Senda-Cook. “Location Matters: The Rhetoric of Place in Protest.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 97, no. 3, 2011, pp. 257-282.

Foucault, Michel. “Orders of Discourse.” Social Science Information, vol. 10, no. 2, Apr. 1971, pp. 7-30.

Fraser, Nancy. “Rethinking Recognition.” New Left Review, vol. 3, no. 3, 2000, pp. 107-120.

Devito, Lee. “While Artist Sintex Fights ‘Culture Vultures,’ Detroit Gears up for a Graffiti Crackdown.” Metro Times, Detroit Metro Times, 2015, http://www.metrotimes.com/detroit/while-artist-sintex-fights-culture-vultures-detroit-gears-up-for-a-graffiti-crackdown/Content?oid=2297092#.

Ghoshal, Raj A. “Transforming Collective Memory: Mnemonic Opportunity Structures and the Outcomes of Racial Violence Memory Movements.” Theory and Society, vol. 42, no. 4, 2013, pp. 329-350.

Grand River Creative Corridor. “Official Statement: Defacing of Vincent Chin Mural.” Grand River Creative Corridor Facebook Page, 2014, https://www.facebook.com/GRCCDETROIT/photos/a.121046951373103.30480.100439420100523/503701233107671/?type=1&theater.

Harris, Aurora. Personal Interview. 6 May 2020.

Hoang, Haivan V. Writing Against Racial Injury: The Politics of Asian American Student Rhetoric. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015.

Hunter, George. “Revival of Detroit’s Cass Corridor crowds out criminals.” The Detroit News, www.detroitnews.com, 2016, http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2016/07/12/detroit-evolving-cass-corridor-criminals/87010800/.

Kärrholm, Mattias. “The Materiality of Territorial Production: A Conceptual Discussion of Territoriality, Materiality, and the Everyday Life of Public Space.” Space and Culture, vol. 10, no. 4, 2007, pp. 437-453.

Kim, Barbara W. “The Ties that Bind: Asian American Communities without ‘Ethnic Spaces’ in Southeast Michigan.” Ethnic Studies Review, vol. 30, no. 1/2, 2007, pp. 75.

Laux, Hans Dieter and Günter Thieme. “Koreans in Greater Los Angeles: Socioeconomic Polarization, Ethnic Attachment, and Residential Patterns.” From Urban Enclave to Ethnic Suburb: New Asian Communities in Pacific Rim Countries edited by Wei Li. University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 2006, pp. 95-118.

LaWare, Margaret R. “Encountering Visions of Aztlán: Arguments for Ethnic Pride, Community Activism and Cultural Revitalization in Chicano Murals.” Visual Rhetoric: A Reader in Communication and American Culture, edited by Lester C. Olson, Cara A. Finnegan, and Diane S. Hope. SAGE Publications, Inc., 2008, pp. 140-153.

Li, Wei. “Anatomy of a New Ethnic Settlement: The Chinese Ethnoburb in Los Angeles.” Urban Studies, vol. 35, no. 3, 1998, pp. 479-501.

Ling, Huping. Chinese St. Louis: From Enclave to Cultural Community. Temple University Press, 2004.

Liu, Michael, and Kim Geron. “Changing Neighborhood: Ethnic Enclaves and the Struggle for Social Justice.” Social Justice, vol. 35, no. 2, 2008, pp. 18-35.

Mao, LuMing, and Morris Young. Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric. USU Press, 2008.

Massey, Doreen. For Space. Sage Publications Inc., 2005.

Meyer, Michaela D.E. “‘Maybe I Could Play a Hooker in Something!’ Asian American Identity, Gender, and Comedy in the Rhetoric of Margaret Cho.” Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric, edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young. USU Press, 2008, pp. 279-292.

Neavling, Steve. “Popular Detroit Artist Defaces Tribute to Asian American Icon Vincent Chin.” Motor City Muckracker, 2014, http://motorcitymuckraker.com/2014/08/18/popular-detroit-artist-defaces-tribute-to-asian-amerian-icon-vincent-chin/.

Ong, Rory. “Transnational Asian American Rhetoric as a Diasporic Practice.” Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric, edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young. USU Press, 2008, pp. 25-40.

Pham, Vincent N. “The Exiled Speak Back: Citizenship and Belonging in the White House ‘What’s Your Story?’ Video Challenge.” Enculturation, no. 27, 2018, http://enculturation.net/exiled-speak-back

Pham, Vincent N. and Kent A. Ono. “‘Artful Bigotry and Kitsch’: A Study of Stereotype, Mimicry, and Satire in Asian American T-Shirt Rhetoric.” Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric, edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young. USU Press, 2008, pp. 175-197.

Rahal, Sarah. “Asian American Community Sees Signs of Resurgence in Detroit.” The Detroit News, 2019, https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2019/02/18/lost-asian-american-community-detroit-sees-reason-hope/2744890002/.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer. “Sounding Asian/America: Asian/American Sonic Rhetorics, Multimodal Orientalism, and Digital Composition.” Enculturation, no. 27, 2018, http://enculturation.net/sounding-Asian-America

Staeheli, Lynn A., Don Mitchell, and Caroline R. Nagel. “Making Publics: Immigrants, Regimes of Publicity and Entry to ‘The Public’.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 27, no. 4, 2009, pp. 633-648.

Stamm, Alan. “Update: Chin Mural ‘Defacing…Saddens All of Us,’ Grand River Group Says.” DeadlineDetroit, 2014, https://www.deadlinedetroit.com/articles/10169/update_chin_mural_defacing_saddens_all_of_us_sponsoring_group_says.

Taylor, Charles. “The Politics of Recognition.” Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition, edited by Charles Taylor and Amy Gutmann. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J, 1994, pp. 25-73.

Warner, Michael. The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics and the Ethics of Queer Life, Free Press, 1999.

Wasacz, Walter. “The Yin and Yang of Detroit’s Fastest Changing Neighborhood.” Model D, 2016, http://www.modeldmedia.com/features/chinatown-development-082916.aspx

Watson, Sophie. City Publics: The (Dis)Enchantments of Urban Encounters. Routledge, 2006.

Wells, Karen. “The Material and Visual Cultures of Cities.” Space and Culture, vol. 10, no. 2, 2007, pp. 136–44.

Wey, Tunde. “People: Soh Suzuki.” Detroit Urban Innovation Exchange, 2012, http://www.uixdetroit.com/people/sohsuzuki.aspx.

Wheeler, Anne. “Rendering Everyday Life: Tactical Artwork by Incarcerated Japanese American Artists.” Enculturation, no. 27, 2018, http://enculturation.net/rendering-everyday-life

Võ, Linda T., and Rick Bonus. Contemporary Asian American Communities: Intersections and Divergences. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2002.

Young, Morris. Minor Re/Visions: Asian American Literacy Narratives as a Rhetoric of Citizenship. Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

Zhou, Min, Yen-Fen Tseng, and Rebecca Y. Kim. “Rethinking Residential Assimilation: The Case of a Chinese Ethnoburb in the San Gabriel Valley, California.” Amerasia Journal, vol. 34, no. 3, 2008, pp. 55-83.