Jason Luther, Rowan University

Kristin Prins, Cal Poly Pomona

Frank Farmer, University of Kansas (Emeritus)

(Published April 26, 2023)

A woman-owned community print shop. Textile art made from salvaged materials. An open-source feminist hacker zine. A free skool that teaches UX. A makerspace in a public library. An independently published children’s book about lowriders. For the last several years, we have worked with a loose collective of scholars devoted to Do It Yourself (DIY) approaches to teaching writing.[1] In what follows, we elaborate on the claim that, for ourselves and many colleagues, there exists something that can, and should, be properly referred to as DIY composition. Then, we identify characteristics of what we mean by this term, as well as scenes where DIY composition occurs. In announcing our purpose, we immediately become aware of any number of concerns, the most important of which, we believe, are definitional. What exactly is DIY, and more crucial to our argument, what is DIY composition?

We do not mean DIY in its conventional usages, such as what a viewer might find on the DIY Network or what consumers pursue when foraging the aisles of supply stores such as The Home Depot or Lowe’s, in other words, DIY as a pleasant hobby or weekend activity, a cozy and familiar “suburban kind of phenomenon” (Gauntlett 49). This corporate understanding of DIY is at a considerable remove from our own. Matters get a bit more complicated when we try to define DIY composition. DIY holds a distinct position within a constellation of related terms, all of which have been markers for trends and developments in rhetoric and composition, as well as writing studies. Take, for example, the widespread enthusiasm for making and maker pedagogies. Such enthusiasm, no doubt, derives in part from the influence of the Maker Movement, and the recent appearance of campus makerspaces. While we applaud these developments, we are also aware that not all making is DIY making, even though all DIY inevitably entails the making of something. Predating the Maker Movement, a resurgent interest in craft, starting in the 1990s, is also relevant. Not all craft is DIY craft, but all DIY includes some features of craft, broadly understood.

In our understanding, DIY is a cultural rhetoric that fosters creative and critical making, that promotes an ethos of making do, and that circulates within fluctuating networks of rhetorical and artistic production called scenes. These three characteristics, we argue, are constituent aspects of a cultural rhetoric that aspires to contest the readymade quality of lived life. In disputing workplace, consumer, and cultural readymades, DIY voices a sometimes explicit, but more often implicit, politics not always found in discussions of making or craft (Ramage 46–61). In a word, DIY has a distinctive attitude toward hand-me-down or off-the-rack norms for how things must get done or made. Such an attitude bespeaks a kind of politics, though one not always readily apparent or overt. This is a politics of world making, to borrow Michael Warner’s phrase, but also a politics that ultimately yearns to be transformative, or world changing. For this reason, we conclude our essay with a nod to DIY’s utopic function, its hope for more democratic participation in making a world not already packaged for its inhabitants.

Our definition of DIY is, of necessity, a preliminary one. In what follows, we survey DIY’s history as a movement, including relevant DIY scholarship, while exploring each of the key aspects of our definition more fully. But first, why DIY, specifically? Why not craft or maker composition?

Why DIY?

DIY, craft, and making can all describe human self-provisioning activities up to industrialization, and some subset of those activities since then. These are useful terms for considering the ways material culture is created—and how doing so shapes cultures and is shaped by them. From Indigenous uses of plants for medicine, to Amish barn raising, to largely white Stitch ’n Bitch knitters making pussy hats, what is made, who makes it, how it is made, and why it is made is contingent on culture. All three terms point to productive activity creating things that could now, broadly, be procured through markets. DIY, craft, and making are done more efficiently by industries at scale. And people’s reasons for doing it themselves vary widely: factors can include tradition, politics, community, necessity, creative control, enjoyment, environmental concern, and more. As we will discuss, the making itself makes a difference in what is created: self-produced music means something different from an album produced by a major record label owned by an international conglomerate, and hand-cut and hand-sewn fringe on a shawl means something different from that which was mass-produced (Arola, “Composing” 275, 279–280). Why, though, DIY, specifically?

Craft tends to emphasize traditional hand-making of high-quality items at a non-industrial scale by experts who own their means of production. The Arts and Crafts Movement’s ideals, discussed below, are a good example of this. However, there are historical examples of digital, industrial-scale, and capitalist craft (see McCullough, Sinopoli, and Kristofferson, respectively). Using craft as a translation of techne (often as “an art or craft”) points to craft’s association with a “skill or skilled occupation, an ability in planning or performing, ingenuity in construction, or dexterity” (Risatti 17). Art historian Glenn Adamson, in Inventing Craft, argues that craft, much like DIY, is a reaction to Western industrialization and depersonalization in the modern period. However, DIY’s ethos of making do stands in contrast with these emphases of craft (xiii).

Despite having perhaps the broadest denotative meaning, making in the 21st century is embedded in a movement defined by digital technologies, digital networks, and individual-scale manufacturing. The Maker Movement is typified by Make magazine and its branded Maker Faires, as well as home manufacturing machines like 3D printers and laser cutters, and novice-friendly electronics and computing kits. While the Maker Movement comes out of traditional tinkering and digital hacking cultures and has functioned as a potentially inclusive and democratic movement in computers and writing, it has also been critiqued (see Breux and Powell, respectively). Many funders of maker initiatives are more interested in creating makers with STEM-related skills to drive down the cost of labor with technical expertise and to create new products to bring to market. In these ways, making has connotations of technical skill development aimed at social and economic capital accumulation and tends to elide social connections and place in ways that DIY does not (Gollihue, Shivers-McNair 20–21).

None of this is to suggest that craft or making are tainted or that DIY is somehow pure—no movement is, as we’ll make clear—but DIY does the best job, for us, of getting at what we see afoot in the field and what we want to create more of. DIY, in many ways, rejects the fussiness about skillfulness often associated with craft (though not the development of skill itself) and accumulation of social and economic capital that comes with making (though it’s not separate from issues of capital, either). DIY, and its related practices “Do It Together” and “Do It Ourselves,” is inherently and expressly political, in part because it demands that we work with what’s at hand and share what we have made before attaining some version of standardized perfection (Ratto and Boler 8).

DIY’s Complicated Past

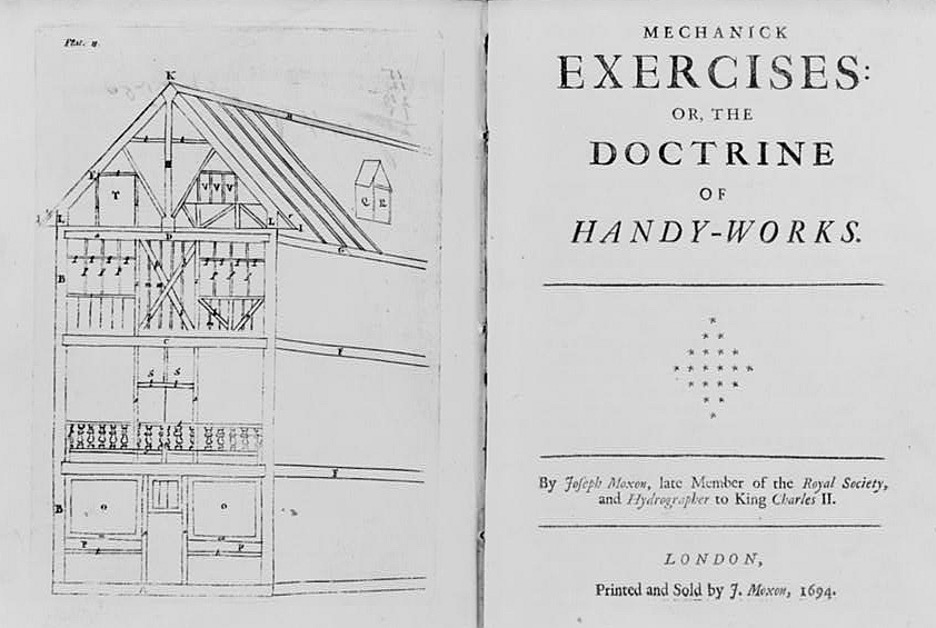

The history of DIY is a braided one, and because it is interwoven with other histories, including those of craft and making, scholars don’t always agree on its precise origins. Moreover, the breadth of activities that could be described as DIY, from home maintenance to musical performance, make it nearly impossible to offer a comprehensive history. It would not be entirely wrong to trace its prehistory to early advice manuals like Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises (1683–1685), or Mary Gascoigne’s Handbook of Turning (1842), or Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help (1859) (Science Museum). Nor would it be mistaken to suggest that eighteenth century American pamphlets and almanacs, including Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack (1732–1758), represent an early form of DIY self-publishing. Of course, Indigenous traditions of making—based on embodied, enmeshed, local ecological knowledge that predates and informs DIY practices traced from European traditions—and African American traditions like quilting can also be named DIY. These examples are historical forerunners to contemporary DIY, though they are not usually centered in DIY’s histories.

Figure 1. Architectural sketch and title page for Joseph Moxon's book Mechanick Exercises (1694)

In tracing historical lineages, we are on more familiar ground in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[2] While we tend to see the Arts & Crafts Movement (1880–1920), an international phenomenon originating in England, as an example more of craft because of its focus on material integrity and skilled hand production, David Gauntlett identifies it as an especially noteworthy precursor to later and more familiar understandings of DIY. Importantly, the movement embraced an avowed politics, with many of its followers urging social reforms along with an anti-industrial ethos. Gauntlett points out that “the American inheritors of the Arts & Crafts Movement added the democratic element which today we would call ‘DIY culture’” (48).[3]

Following Arts & Crafts, another important chapter in mainstream DIY history occurred when the first science fiction fanzines appeared in the 1920s. These literary self-publications spawned a variety of other specialty zines devoted to musical genres, subcultures, marginal identities, and politics, a tradition that continues into our present moment. DIY eventually migrated into other cultural practices and activities, and its expressions appeared in often surprising forms.

In the 1950s, for example, music became more widely democratized. The musical phenomenon known as skiffle, a grassroots folk genre heavily influenced by jazz and blues, reached its zenith in this decade. Its defining feature was that it was performed on homemade instruments: “the tea chest with a broom handle attached . . . the simple washboard . . . the jug, kazoo, cigar-box fiddle, and comb and paper” (Spencer 187). According to Amy Spencer, skiffle was the original lo-fi musical expression, “based on the realization that you don’t need the most expensive instruments or the most high-tech recording equipment to make good music, but can instead celebrate what resources you have” (188). At the same time, DIY had another influence in the way music was circulated to listeners and fans. Pirate (aka “bootleg”) radio, unlike skiffle, did not turn its back on existing technology in favor of homemade alternatives. Rather, it appropriated existing technology to repurpose it for unauthorized and sometimes illegal ends.

Skiffle and pirate radio continued into the 1960s, as did the always formidable problem of access. In that decade, the most important event in mainstream DIY history was the publication of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools (WEC, 1968–1972), whose subtitle alludes to the very problem that WEC tried to resolve: how do ordinary people gain access to means of production? WEC’s answer was to offer “readers a (mostly mail-order) gateway to all kinds of resources, including information, technical books, and courses, as well as physical tools such as those for building, metalwork, gardening, and early electronics” (Gauntlett 51). For obvious reasons, WEC is occasionally referred to as the “bible of DIY,” and in one respect, this seems especially true, for WEC is indeed prophetic, anticipatory. The values that inform later versions of DIY can be found in WEC, and the embrace of technological innovation as DIY can be discovered here too. Indeed, as a visionary entrepreneur, Brand went on to promote advances in technology and is even credited with coining the phrase “personal computer.”

A very different emphasis on tools comes from Ivan Illich at the beginning of the 1970s. It would be unwise to proclaim any thinker as the grand theorist of DIY (a contradiction in terms, at best), but if anyone could lay claim to the title, Illich is the most likely candidate. He is best known for his work Deschooling Society (1971), but his version of social anarchism includes several other works that are not only anti-industrial, but also anti-institutional and anti-professional. Illich’s corpus trenchantly criticizes our most esteemed institutions, especially schooling and medicine. The most influential of his works, Tools for Conviviality (1973), argues for communal interdependence by sharing knowledge, tools, and resources within (presciently, we note) decentralized webs or networks. Like Brand, Illich’s thinking is a reclamation project, the “taking back” of what properly belongs to people making, working, and living together. Both Brand and Illich are intellectual harbingers of what many regard as a watershed moment in the history of DIY: its reemergence in concert with the arrival of punk music and culture.

In the year before the Sex Pistols released their only studio album, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols (1977), artist, activist, and journalist Carolyn Coon used the term “DIY” in the music magazine Melody Maker (1976). This usage of initials was not the first, but Coon was right in understanding that punk brought new significance—and new energy—to what had been previously meant by DIY. Not surprisingly, DIY in this new version became the guiding ethos of punk and alternative culture, an ethos most famously voiced in what became a legendary motto of punk appearing in first issue of the fanzine Sideburns in 1977 and capturing punk’s attitude of defiant independence: “This is a chord, this is another, this is a third. Now form a band” (Moon).

The DIY ethos was also apparent in the abundance of punk zines that emerged alongside punk music, that promoted certain bands and events, and encouraged, as well, the DIY ethos that suffused punk culture. If punk sought to wrest control of music making from corporate ownership and control, then zines sought to do the same for publication. Both DIY expressions, taken together, articulated a subcultural critique of consumer capitalism. Punk’s critique was felt, lived, and experienced by adherents who shared a common identity and (often) an attitude toward official culture and its many exclusions. DIY, so understood, may be interpreted as a response to alienated labor, since ordinary consumers (workers, artists, and citizens) used tools and materials at hand to create objects and networks that validated and sustained them. When such activity is widespread, and collectively pursued, it serves as both a rebuke to guarded systems of knowledge and an invitation to imagine and advocate for new amateur knowledges and arrangements not recognized by existing institutions.

In the decades to follow, punk gave way to new musical genres and subgenres, and zines proliferated, becoming more diverse in the issues and themes addressed in their pages. Though both forms moved well beyond their earliest beginnings, they were able to retain some flavor of the DIY spirit that characterized their origins in the mid to late 1970s. In fact, the next watershed moment in DIY owed much to punk, even as it sought to upend punk’s sexism and misogyny.

In the 1970s, punk and zine cultures were overwhelmingly male oriented, but in the 1980s, a nascent feminism emerged in both music and self-publication. The zenith of this development was undoubtedly the Riot Grrrl Movement of the early 1990s, which is credited for what later became known as third-wave feminism. The figure most associated with Riot Grrrl is Kathleen Hanna, a musician and activist, author of the zine Bikini Kill, and leader of the band by the same name. In her zine, Hanna published a manifesto that stated her rationale: Why Riot Grrrl?

BECAUSE us girls crave records and books and fanzines that speak to US that WE feel included in and can understand in our OWN ways. BECAUSE we wanna make it easier for girls to see/hear each other’s work so that we can share strategies and criticize- applaud each other. BECAUSE we must take over the means of production in order to create our own meanings. (qtd. in Spencer 50)

This is DIY understood through a particular feminist sensibility, at a particular moment in time, among a particular group of young women disenchanted with received versions of feminism. Riot Grrrl was not only enormously influential in expanding the possibilities of how feminism might be defined, but also in opening up punk DIY to gendered analysis. More than this, Riot Grrrl also demonstrated a keen sensitivity to the politics of representation, calling for a media blackout in 1992, wary of the establishment press, fearing that their issues “would be trivialized in media accounts” (Spencer 51). Instead, they relied on zines and zine networks to circulate news and notices of the Riot Grrrl scene, as well as to disseminate their particular DIY ethos. As Sara Marcus puts it in her history of Riot Grrrl, they used their available means as “vital forces to be struggled with and shaped, experimented with and created, breathed and lived” (37). Riot Grrrl appeared at a moment immediately prior to the wide accessibility of the internet. Although DIY’s current renaissance could be explained by mere nostalgia, we believe it also points to DIY’s shapeshifting ability to be reinvented according to people’s changing needs and historical conditions, especially when new tools and technologies become available.

Since the advent of Web 2.0, for example, a revived interest in DIY can be observed in numerous ways made possible by digital affordances. Web design, app making, YouTube, Flickr, ezines, TikTok, Ravelry, Twitter, blogs, vlogs, open-source sharing, and online distros are just some digital environments where DIY opportunities have emerged. Over a decade ago, David Gauntlett pointed out that the Web “is, of course, vast. There’s no point trying to describe all of the creative things that happen there, because there’s just so much of it” (82). Since then, the creative possibilities of digital networks have multiplied exponentially. But does this mean that contemporary DIY must be limited exclusively to its digital expressions?

Absolutely not. Digital media has by no means replaced old media. Instead, what has emerged, insofar as DIY is concerned, is a fruitful relationship between the two, and the DIY affordances they provide together. This can be seen in, for example, Jody Shipka’s advocacy of remediation, or semiotic remediation, as key to her understanding of multimodality. In revisiting old or analog media through the framework of new or digital media, we can, in some measure, make old media new, transforming our prior understandings of what received forms once meant—and what they could mean in the future. Additionally, DIY in the present moment can also be considered a response to our awareness that the digital is now increasingly taken for granted, ubiquitous, routinized; this familiarization is often referred to as the postdigital.

While our history of DIY has been necessarily brief, it serves as both foundation and springboard to the discussion that follows. This history functions in conversation with how composition scholars have thus far used DIY perspectives in their disciplinary work, primarily as a means for offering alternatives to writing as professionalization.

Valuing the Amateur in Rhetoric & Writing Studies

Thus far, we have argued that DIY has historically positioned itself as an alternative to readymade/corporate/consumer culture, highlighting a rift in motive between amateur and expert. By definition, amateurs participate in labors of love, repairing, repurposing, and cobbling together their available means to create objects and networks that validate and sustain them. DIY, then, is an empowering directive to make things that might otherwise be acquired from a professional or the marketplace.

While rhetoric and writing studies has not fully theorized DIY or amateur production, it has participated in its share of rebukes toward the corporate university and its own commodification through the professionalization of writing. Responding in part to its increasingly taxonomic, codified approach to the writing pedagogy in the late 1970s and 80s, the field began a series of reflexive critiques of its own complicity in cleaning up the lowly commoner discourses of students, hiding curricular agendas, and preparing a literate workforce. Starting in the 1990s, several book-length counter-histories reassessed the direction of the discipline, including Susan Miller’s argument to build political agency in the margins in Textual Carnivals: The Politics of Composition (1991); Anne Ruggles Gere’s invitation to trace literacy learning outside the classroom in Intimate Practices: Literacy and Cultural Work in U.S. Women's Clubs, 1880–1920 (1997); Sharon Crowley’s audacious call to abolish the first-year writing requirement in Composition in the University: Historical and Polemical Essays (1998); Byron Hawk’s recovery of vitalist-ecological complexity in A Counter-History of Composition: Toward Methodologies of Complexity (2006); and more recently, Leigh Gruwell’s reclamation of craft in Making Matters: Craft, Ethics, and New Materialist Rhetorics (2022).

Again, while DIY culture has been largely absent from these critiques, Geoffrey Sirc comes as close as any to articulating a kind of DIY composition. Sirc attempted to “reread the almost erased palimpsest of punk, on which our field’s official history has been overwritten,” in 1997’s “Never Mind the Tagmemics, Where’s the Sex Pistols?” (later revised as a chapter in 2002’s English Composition as a Happening). This work previewed some of the important through lines that have dominated our discipline since the turn of the century, including a reconsideration of the role of process pedagogy (10). In this re-reading of punk, Sirc finds a radical, unforgettable potential that was antithetical to the “NO FUN” (21) organizing schemes that dominated the discourse of composition in the late 1970s, which valued, among other things, the “professional over the amateur” and thus ignored the ways in which “punk pedagogy was DIY” (21).

While DIY is not mentioned again in the article, Sirc evokes many of its practices through his descriptions of the creative processes of punks, which “didn’t discard pre-writes, jotted notes, general ideas—it lived off them”; embraced an “aesthetic of the cut-up, re-making/remodeling the material of the domain culture”; and wrote on “the media of collective space—fashion, graffiti, music, crime” in its reverence for a negation which all called attention to the pointless pursuit of “righting writing” (13–15). While he liberally drew from the palimpsests of Greil Marcus, Jon Savage, and Dick Hebdige to juxtapose a scene of punk against a restrained disciplinary scene of composition, the article fell short of offering any actual pedagogy—which was the point. Sirc seemed to embody a punk ontology that negated the teaching of writing altogether.

However, a year later, Sirc clarified that he was not so much negating writing pedagogy as calling out the field’s unhealthy obsession with professionalization. In CCC’s “Interchanges: Punk Comp and Beyond” Sirc and Seth Kahn-Egan reconsider “Never Mind” with Kahn-Egan using his title to announce a “pedagogy of the pissed.” In service to this pedagogy, Kahn-Egan lists five principles of punk, including “The Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethic” which “demands that we do our own work because anybody who would do our work for us is only trying to jerk us around” (100). For Kahn-Egan, this translates to a social-epistemic pedagogy, where students “move from being passive consumers of ideology to active participants in their cultures” (100). That is, Kahn-Egan imagines the DIY ethic as a means for encouraging students who have “little sense of responsibility to their cultures”; he thus proposes curricula that use this DIY sensibility to produce critique (101).

Sirc’s response to Kahn-Egan’s earnest appropriation of punk was more negation, starting with the deflating notion that a “heavy nostalgia” hangs over any punk curriculum. “I’d hate to make anyone share my enthusiasms,” he writes. “I’d get creeped out, feeling like Alan Bloom playing students his Mozart records” (104). He goes on to describe Kahn-Egan’s courses as having a “sentimental aspect,” wondering if the composition classroom, or the academy, could ever really deliver on its desire for reform (105). Sirc, in other words, is after something more situated and authentic, a happening inspired by events beyond the confines of the workplace or the classroom, the kind of composition that “explores the wound . . . composition not meant to take a stand or fix a problem, but simply to reflect on possibility, to chronicle changes, just changing and having the chance to change” (108; emphasis in original).

Sirc’s dissatisfaction previews much of what composition responded to in the new century, revisiting and reinvigorating the role of process pedagogy—“to reflect on possibility” and “to chronicle changes,” as he put it—through both post-process theory and multimodal composition. What brings these two threads together is a greater emphasis on the materiality of writing, what we use to compose, and who and what we compose with. Multimodality has been especially popular among compositionists over the last two decades, largely for this reason. Composition teachers routinely assign students to make projects—podcasts, videos, zines, exhibits—that require them to deploy two or more semiotic modes (visual, linguistic, spatial, aural, and gestural) in service to some communicative purpose. A number of prominent figures in composition have made multimodal writing a standard practice, including, among others, Anne Frances Wysocki, Jason Palmeri, and Jody Shipka. Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes, as well as Adam Banks, Cheryl Ball, and many others have also explored the affordances of new media and digital technology to multimodal writing. This begs the question, however: when does multimodal writing approach DIY composition?

Of all scholars of multimodality, we believe Shipka best illustrates the DIY ethos, both in terms of her theories of multimodal composing—which posit that everyday communicative processes are present, in flux, highly distributed, and embodied, and therefore never limited to the digital—and especially in how her nontraditional scholarship walks the walk through its various performances, forms, and manifestations. After publishing Toward a Composition Made Whole, Shipka made films from found objects (“On Estate Sales, Archives, and the Matter of Making Things”), composed with food (“Edible Rhetoric), and led national workshops on composing with everyday things (“Evocative Objects”). The sense of possibility explored in this kind of work—the ways in which everyday encounters with people, objects, and settings can be transformed into multisensory, material things—has been parlayed in more recent texts on making and craft.

The multimodal turn and contemporary DIY movements like the Maker Movement have had noticeable and positive influences on rhetoric and writing studies. They call attention to places like writing centers and multimedia studios, where writing and writing instruction happen: disruptive spaces that are invented without permission and have the capacity to create moments of advocacy, as Joyce Locke Carter has argued. We highlight some of these later in the article through the DIY concept of scenes. Taken together, these assorted developments establish the broad contours of an intellectual context favorable to a revitalized DIY—and, for our purposes, the emergence of what we understand as DIY composition. Below, we present a theory of DIY composition, drawing from cultural, material, public, and spatial rhetorics to articulate pedagogical praxis in various scenes within rhetoric and writing studies, from our classrooms to our publishing platforms.

Toward a Theory of DIY Composition: Cultural, Material, and Scenic Orientations

Above all, we understand DIY composition as a rhetorical and material response, rooted in a desire to create alternatives to the mainstream models of material and cultural production. Emphasizing community self-reliance and self-provisioning, these alternative models speak to varying practices, identities, and scenes that span the globe. The articulation of these alternatives to prevailing dominant political, cultural, and economic forces has historically marked DIY as an important variation within the deeper traditions of craft and making, traditions that carry with them a range of cultural rhetorics that speak to creative, critical, and economic needs. To reprise our opening definition, and as we endeavor to square DIY culture with rhetoric and writing studies, we outline three interrelated features: First, DIY is a cultural rhetoric that fosters creative and critical making; second, DIY’s ethos is one of making do, whether out of necessity or by choice; and third, DIY cultural rhetoric circulates through scenes: fluctuating networks of rhetorical and artistic production. These three characteristics are constituent aspects of a cultural rhetoric that has mostly gone unrecognized by our field, one that remains to be fully explored by writing teachers and scholars. In what follows, we hope to launch such an exploration, surveying relevant DIY scholarship while elaborating on our preliminary understanding of DIY composition.

DIY is a Cultural Rhetoric

Those who participate in DIY culture make things that challenge or circumvent the readymade, and they do so through processes we have described as world challenging and world making. These processes are rhetorical, and the cultural practices by which such things are made are determined or inflected by the communities that make them. In this way, we want to theorize DIY as an interaction between culture and rhetoric and consider how this interaction produces particular meanings and systems of meaning over time. As cultural rhetorics scholars have noted, the relational and constellated nature of culture and rhetoric helps resist objectifying culture, calling attention to the ways “people make things (texts, baskets, performances), people make relationships, people make culture” (Powell, et al.). This, in turn, emphasizes how “knowledge is never built by individuals but is, instead, accumulated through collective practices within specific communities” (Bratta and Powell).

Such relationality, as Angela Haas points out, is ongoing and involves “the negotiation of cultural information—and its historical, social, economic, material, and political influences—to engage participation and social action, broadly understood” (Cobos, et al. 145). For us, DIY culture’s influences—including its histories, objects, languages, technologies, labor conditions, and belief systems—must be negotiated through the rhetorics of DIY, how the meaning of certain practices/actions (“do”), processes/activities (“it”), and bodies/collectives (“yourself,” “ourselves”) lead to different conceptions of agency, often framed through tropes of creativity, liberation, utility, critique, sustainability, profit, or an amalgamation of these. As Jennifer Sano-Franchini has argued, a cultural rhetorics perspective is also “based on the premise that rhetoric has been and always will be a culturally located practice and study” (52). As such, cultural rhetorics can help parse out rhetorical tactics and dynamics within these culturally specific, situated locations, whether these are DIY venues, makerspaces, or farms. Representation, then, can “come with multiple and sometimes conflicting implications for many different groups of people—people who are complicated and whose identities are entangled in webs of meaning” (Sano-Franchini 59–60). Again, depending on their varying access to power, the identities of participants in DIY culture are complicated by rhetorics that speak to creativity, dissent, liberation, participation, and entrepreneurship—and often all at once. These rhetorics convince both makers and consumers that DIY’s processes and products are authentic or thrive outside contemporary models of capitalist production, while always already existing in relation to those models.

Prosumer rhetorics offer one example of this complexity. Building from Alvin Toffler’s concept of prosumption in The Third Wave, Estee Beck suggests that the ethos of DIY is often marketed through a “hype of self-reliance” that “shifts the expense of labor onto consumers,” a shift that has enabled contemporary tracking technologies, predicated on a rhetoric of sharing, that often lead to algorithmic surveillance (“Sustaining” 39, 42). While critical of this trajectory, Beck acknowledges how DIY culture has also eroded specialization and provided greater access to tools and literacies that provide participants with more agency. Moreover, Beck distinguishes between an exploitive “commodity prosumerism” and an empowering “open source” version that rhetoric and composition scholars have forwarded through new media production and multimodal pedagogies. She cites Daniel Anderson, for instance, who defined prosumerism twenty years ago as the “convergence of professional and consumer level equipment and software”—a definition that emphasized agency for both professionals, who could “do things with less,” and amateurs, who had greater access to tools (Anderson).

While such permissive rhetoric can be advantageous, Beck notes that the mass use of communication technologies has led to a culture where, among other consequences, the creative class is compelled to promote their work in an attention economy whose primary profit is derived from digital algorithmic surveillance. Put another way, the same DIY ethos that fosters critical engagement also promotes a discourse of overcoming barriers between production and consumption, often at a cost. For us, this means that rhetoricians must attend to DIY’s capacity to require consumers to perform acts of productive labor through unofficial practices and feelings of participatory empowerment. Beck suggests such empowerment thrives on an “opt-in rhetoric of sharing,” which has helped publicize certain dimensions of DIY culture in the mainstream (“Sustaining” 37).

For this reason, some critical makers develop materially engaged cultural practices that emphasize reflection, taking time and building community-based practices that consider the role of mediation in social reproduction to thereby “uncover and explore conceptual uncertainties, pars[ing] the world in ways that language cannot,” as Matt Ratto argues (227). Whether users tinker with analog electronics, recode proprietary software, or print zines, when framed as communal participation, these practices can potentially ripple outward as forms of “DIY citizenship,” a term Ratto and Megan Boler use in their edited collection by that name. In numerous examples throughout this collection, DIY-inspired makers do not just do it themselves but do it together (DIT) or with others (DIWO) as they pursue collective social action. These critical makers also reflect on their ethics and collaborate on goals through social, rhetorical practices, presenting a means for challenging disturbing dimensions of DIY culture, including those propagated by venture capitalists, racist skinheads, and alt-right YouTubers.

Such a dark side reminds us that maker subjectivity itself is determined by cultural rhetoric. Treating DIY as a cultural rhetoric makes room for its capaciousness and contradictions, allowing scholars to raise questions about its suasive effects: What tropes or stories exist in DIY cultures that function as rhetorical strategies? What genealogies and epistemologies have informed them? Under what cultural contexts is making framed as collective or entrepreneurial? How do appeals to participation, self-reliance, authenticity, and radicalism get inscribed through DIY contexts and practices? When is DIY rhetorically creative and critical, and when are amateurs interpellated? Moving forward, we might consider how certain practices of collaboration and reflection lead to critical and creative approaches to DIY composition that help makers understand how their materials and their work are constellated with other humans, non-humans, intermediaries, and objects. For this reason, we approach DIY composition as an ethos that considers the exigencies and limitations of any given rhetorical situation, whether one is limited by knowledge, materials, or technologies. DIY culture calls such tenacity making do.

DIY Makes Do

Much of the DIY home improvement boom in the 1950s bolstered the standard of living of those already comfortably in the middle class, which continued through the emergence of big-box craft supply stores in the 1970s and 80s, as well as Home & Garden Television (HGTV, launched in 1994) and its spinoff, the DIY Network (1999), Make magazine (2004), and the image-sharing social media platform Pinterest (2009). The particular aesthetics associated with these movements and media, upholding stylized professional polish, have tended to benefit those who can afford time and materials to practice, ready-made kits, or forgoing the “doing it yourself” part altogether to purchase factory-made goods with a DIY aesthetic. However, people who go this route will usually freely admit that is not real DIY, because they did not make, or make do, with what was at hand.

As the core ethos of DIY culture, making do permeates DIY practice. From the simplicity of Shaker furniture or craftsman architecture, the simple three-chord structure of punk rock, or community potlucks that respond to local food insecurity, DIY culture is founded on making more with less. This ethos can apply to every aspect of living: repurposing secondhand clothing, growing sustainable vegetable gardens, rehabbing homes using salvaged materials, forming cooperatives, or, as Avery Edenfield and Lehua Ledbetter explain, sharing DIY hormone replacement therapy (HRT) information and practices among trans people. Making do is often an act of reclaiming agency in contexts of structural disempowerment while working around established systems. These acts of reclamation and circumvention are, to be sure, often prompted by inadequate community support and by monetary need, and we do not want to glamorize marginalization or poverty—quite the contrary. However, we acknowledge the creative, material, and manual knowledge and the labor of self-provisioning.

DIY embodies an ethic of making do in a second sense: it’s what we do when we confront the potentials and contingent realities of working with materials and tools, and make decisions on how to proceed based on those contingencies. Colin Lankshear and Michele Knobel point to the “‘make do’ and ‘invent on the fly’ character” of the work undertaken by dancehall DJs in Jamaica in the 1960s, when they drew on the “potentials of . . . turntables, magnetic tape, [and] audio tape recording . . . to remix songs” for live audiences (8). Curator and art critic Peter Dormer similarly argues that “thinking in the crafts resides . . . in the physical processes involving the physical handling of the medium [in which one is working],” which “allows the maker’s intentions to develop and change in response to what [they are] creating over a period of time” (24, 80).

This dimension of making do is discussed by Shivers-McNair as disequilibrium, which is an openness to learning on the fly, to trial and error, to the unfolding intra-action (via Karen Barad) of making (66–89). Disequilibrium is generated in many DIY contexts, especially when the person doing-it-themselves or the people doing-it-together are new to what they’re doing. Another example is Krystin Gollihue’s notion of “bumping up” against the nonhuman world in her research on the agricultural production on her family farm in North Carolina as a form of making. Engagements with beehives, red clovers, and garlic scapes are opportunities for the land to “call on” and “teach” her mother/research participant Wendy “how to treat it, how to walk along, upon, and beside it” (28–29).

Further, crocheters encounter the weight and give of yarn, the slipperiness or stickiness of a hook, the tension with which they hold hook and yarn. They also work with dropped stitches and the fact that crochet is particularly well-suited to lacework. Writers of alphanumeric text confront denotations and connotations of words, the possibilities for emphasis in syntax, and reader expectations attached to genre. Anne Wysocki’s definition of “new media texts” seeks, in part, to encourage us to see writing as material that can be both “seen” and “physically manipulated” (22)—and, as writers know, writing also pushes back. Getting comfortable with the disequilibrium of bumping up against the nonhuman is key to navigating DIY practices.

In a final sense, the ethic of making do is about choosing to stay in the realm of DIY or craft production, without scaling up to industrial production or the efficiencies often demanded by capitalism. By sacrificing these efficiencies, DIYers also sacrifice the capital investment, mass production and distribution, and profit that can accompany them. Though crafters may earn living incomes from their labor, they don’t profit from the surplus value created through industrial-scale production. Likewise, DIY composition sacrifices efficiencies of scale (class size, being generalizable and codifiable into textbooks, being easily assessed by the university) and cost (instructor time, nontraditional course materials, etc.).

Without these efficiencies, DIY practitioners are free to undertake what craft theorist David Pye calls a “workmanship of risk,” an approach to making that uses “any kind of technique or apparatus, in which the quality of the result is not predetermined, but depends on the judgment, dexterity and care which the maker exercises as he works” (341–342). He contrasts this with a workmanship of certainty, typified by automated production (342). Work undertaken in a spirit of risk does not, of course, always yield useful results. Pye admits that “in many contexts it is an utter waste of time. It can produce things of the worst imaginable quality. It is often expensive” (343). It remains worthwhile because it produces a wide-open field of possibility: “Free workmanship is one of the main sources of diversity. To achieve diversity in all its possible manifestations is the chief reason for continuing the workmanship of risk . . . ” (352). Pye’s words here are evocative; the praxis section below will illustrate this form of making do in practice.

DIY Emerges in Scenes

We have touched upon the importance of both publics and spaces to our understanding of DIY. What we find curious, though, is the relative scarcity of scholarship that considers these two large themes as interwoven, a whole cloth, so to speak. While there are inquiries into the hybrid construct of public spaces, and while there is a large body of work where the relationship between publics and spaces is implied though not explored, on the whole, attention is typically granted to one of these terms, often to the exclusion of the other.

For DIY, however, publics and spaces are inescapably joined. This is most apparent in the DIY term “scenes,” referring both to specific locations, such as musical venues, and the like-minded people who show up there. According to Emily Hubbard, “The DIY scene is a place where musicians, creatives and other outcasts of society flock to find acceptance and community” (para 16). Put differently, DIY scenes attract people inclined to challenge conventional norms, musical or otherwise, and who do so in often tucked away places. In DIY parlance, then, a scene would necessarily be composed of publics and spaces that overlap or coincide.

But as it turns out, scenes are richer than this, even more encompassing than a simple merging of publics and spaces. According to Stephen Duncombe, one of the first explicators of zine culture, a scene is “the loose confederation of self-consciously ‘alternative’ publications, bands, shows, radio stations, cafés, bookstores, and people that make up modern bohemia” (Notes 58). To this list, we would add certain art venues, street fashion, house shows, flash mobs, pop up events, distros, print shops, makerspaces, and more. Because any given scene is typically “dispersed across space” (Notes 66), it may be likened to a country whose borders, if they exist at all, are evanescent, mercurial, redrawn as swiftly as circumstances might demand. In other words, the scene is deterritorialized. Its scope resists fixed definition, and its emplacements are legion.

Thus, it is not uncommon to hear of “the Detroit scene” or “the Philly scene.” Scenes may also be associated with neighborhoods, streets, or other locales within urban areas. In her cultural history of xerography, Kate Eichhorn often refers to “the downtown scene” in New York City, specifically, the region south of 14th street, during the 1970s and 80s, an area marked at the time by cheap rents, vacant spaces, and, importantly, an abundance of copy shops. Taking a panoramic view, Eichhorn reminds that, “Like most scenes, this one was the result of a convergence of historic, economic, and technological factors” (89). Any scene is thus an ever-shifting complex of cultural trends and developments, not all of which are received warmly by the surrounding culture at large. Further, this complex is often composed of a network of self-conscious outsiders who may not find that larger culture welcoming.

This point is developed by Ben Harley, who describes how a variety of DIY music venues have been the target of alt-right groups like the Right Wing Safety Squad, which is dedicated to shutting down DIY music venues through tactical use of municipal codes and regulations. The group, Harley reveals, is “part of a nationwide campaign by the alt-right to shut down independent music venues and art spaces” because such sites are presumed to be “hotbeds of liberal radicalism and degeneracy” (143). Harley argues that because DIY music venues are “spaces where progressives meet” and often function as “safe spaces for youth from marginalized populations,” they are convenient targets of right-wing activism (144). Perhaps the greatest threat for reactionary groups is that DIY music venues are not “simply spaces where people can hear music; they are spaces where people build community” (145). In these shared worlds, people build relationships capable of persisting beyond any particular event or venue. In this way, scenes foster opportunities for new communities, new identities, new solidarities. Though Harley focuses on DIY music scenes, we think much the same can be said of other DIY scenes, as well.

We have tried to enlarge and complicate the meaning of the DIY term scene as something other than a public or a space, something more than either, whether they are considered together or apart. This is necessary because discussing any particular scene as a public or a space, or both, does not do justice to its richness.

The Pedagogical Scenes of DIY Composition

As we have argued, DIY is a cultural rhetoric that beckons artists, writers, makers, and entrepreneurs to make and make do using available tools, materials, knowledges, literacies, and pedagogies. These resources and activities both emerge from and produce particular scenes of cultural production—material, social, and political formations that both sponsor and are created by participants who coalesce under values of authenticity, frugality, independence, or radical politics. Makers use scenes to share knowledge, practices, and rhetorical goals. In this section, we articulate how such scenes are inherently pedagogical. The most obvious pedagogical scene for composition studies is the writing classroom, but what we mean by classroom gets transformed when refracted through the prism of DIY where it is not identified as a specific location or a packaged set of readymade practices. Rather, the DIY writing classroom is the ground, the occasion, and the exigence for where DIY scenes are most likely to emerge in writing instruction.

Because DIY approaches are primarily learned through self-sponsored experimentation, students and teachers alike embrace what Paul Lynch (after Charles Taylor) refers to as “inspired adhoccery,” an approach where traditional classroom roles are no longer fixed but instead become fluid, reciprocal, or even unnecessary. This approach is not easily squared with classrooms that streamline learning through credit hours, assignment sheets, rubrics, and grades. Rhetoric and writing scholars have disputed such streamlining in writing pedagogies through postprocess theories, where writing is necessarily understood as contingent and situated—and thus frustrating or even impossible to teach.

Drawing, in part, from Lynch, Steph Ceraso and Matthew Pavesich argue that postprocess should encourage instructors to think about how they assemble learning environments, coordinate experiences, or create what they call “postpedagogical encounters” that encourage students and teachers to recursively tinker—invent, test, fail, and restart in processes of design—until they approach rhetorical success. DIY learning, so conceived, is thus one embodied postpedagogical practice that helps students consider what’s possible when we expand multimodal pedagogies to include more than the discursive and the digital. Indeed, Estee Beck notes that such embodiment points to a sixth mode—the tactile—where creators use their bodies to work on, with, and through objects, “colliding and comingling with bodily intent to collect information about objects during interactions and processes of bumping, molding, pressing, pulling—or all the verbs associated with such acts” (“Discovering” 5). For Beck, tinkering upholds a constructionist stance that leads students to develop their own maker literacies, which emerge from a mix of heritage, curiosity, experimentation, and collaboration.

Likewise, we have found that leveraging DIY helps students be more open to play, experiment, and failure in their attempts at making, and to learn from their failures. Indeed, in the DIY classroom, failure is a welcome teacher or mentor. Most people expect to be terrible when they begin learning guitar chords or freehand lettering zines or knitting. DIY experiences can help normalize failure and recontextualize similar failures when students attempt to compose in new ways and new contexts. It can also help them learn to pay attention to where in their process things went awry: Is the medium adequate for the message? Are the materials appropriate for what they are trying to make? Does their process or technique need to be adjusted? Are they using the wrong tool? Are they using the right tool but not yet well? DIY composition invites participants to engage with these and similar questions. This can help them modify their habits of thought and action to become more sensitive to, more flexible with, and more at ease during the work of composing.

Tinkering extends into alphanumeric composing as well. Danielle Koupf, for instance, argues for critical-creative tinkering in the composition classroom, where students engage with writing as a material process by undertaking “rearrangement, substitution, addition, deletion, combination, and reformatting” procedures (par. 8). Koupf describes tinkering as an “open-ended mode of exploration. Writers can tinker to improve earlier drafts, but they can also tinker to produce alternative versions of a text or to try out a new writing technique.” Further, Koupf notes that tinkering “is not rule-governed,” yields “unpredictable results,” and is “not a reparative process” (par. 8). In short, like Pye’s workmanship of risk, tinkering is an inefficient process for producing polished text. Its value is in creating time and space for writers to learn how words and sentences work in different variations and combinations, and through these experiments, novice writers become more proficient users of the tools and materials of writing.

One of us engages students with multiple layers of tinkering via zines, which require students to consider intersections between form and content, and the rhetorical effects of different visual, discursive, and haptic arrangements. Framed within a class that explores both the critical and entrepreneurial impulses of self-publishing, students experiment with various concepts, sizes, circulations, and materials for zine making—from the simple one-sheet mini-zine to a more deliberate public iteration that ultimately gets shared, traded, or sold at one of the largest book festivals in the Northeast. Students are asked to tinker with zine-making through several approaches. First, they observe a range of aesthetics and exigencies by ordering zines from indie bookstores like Quimby’s and QTBIPOC sites like Brown Recluse Distro, as well as browsing examples from the instructor’s library. As students contemplate a wide range of genres, prompts, and weirdo audiences from the zine scene—including titles like Music Men Ruined For Me, Things I Ate: Taiwan Edition, and Worst Party Ever—they encounter possibilities for bricolage in the library, scanning and digitizing images from the stacks or screen-capturing images and fonts from historic newspapers. Students use lab time to cut-and-paste paper collages and manipulate digital ones using free, open access image-editing programs like Seashore and Glimpse, ultimately laying out ideas and adjusting materials based on contingencies or their own feelings of disequilibrium. This extends to reproduction as well; black and white photocopiers distort glossy or colored materials, shift margins, and confound folio collation, but they also offer opportunities like doubling paste-ups from a single letter-sized sheet of paper or exploiting magnification and contrast functions.

This making takes on additional power as students distribute zines to strangers, Little Libraries, and coffee shops, or sell them at a large annual public book festival. When students publicly distribute their work, they participate in scenes of creativity and constellate the classroom with those scenes, blurring the traditional lines between the conventional three-credit classroom and an extracurriculum that has the potential to continue once the class concludes. In fact, because the DIY classroom is, in our view, a portable, mutable construct, it renders the notion of an autonomous extracurriculum rather suspect. At the book festival, for example, where vendors, bookstores, publishers, self-published authors, and independent authors exhibit, students encounter opportunities for embodied sociability, which, in turn, offer new possibilities for scenes where learning occurs.

Figure 2. Saddle stapler and stacks of zines at the Collingswood Book Festival

As anyone who has participated in the mission of community literacy centers, neighborhood service-learning sites, or civic-sponsored makerspaces knows, the curriculum can never be absolutely breached from the extracurriculum. This is especially true in our understanding of the DIY classroom, where, as we indicated above, the classroom is not so much an identifiable place but is, instead, something more akin to a permeable membrane, a porous layer through which ideas, materials, and resources pass back and forth and are transformed in that process. In this way, faculty and students make connections and community through scenes like the knitting club Hannah Bellwoar and Scarlett Berrones discuss in their Harlot piece about yarnbombing their campus clock tower.

Additional scenes of the extracurriculuum include DIY craft projects like the Welcome Blanket Project, which “aims to connect people already living in the United States residents with our country’s newest immigrants through stories and handmade blankets, providing both symbolic and literal comfort and warmth.” Or Sonia Arellano’s research and work with the volunteer group Los Desconocidos’ Migrant Quilt Project , a “grassroots, collaborative effort of artists, quiltmakers, and activists to express compassion for migrants from Mexico and Central America who died in the Southern Arizona deserts on their way to create better lives for themselves and their families.” Kristin Arola, in “A Land-Based Digital Design Rhetoric,” and Angela M. Haas, in “Making Online Spaces,” both argue for using Native American digital cultural rhetorics as models for designing Native-content websites, rejecting the readymade, culturally flattened interfaces of existing platforms. Although this is a small sampling of the DIY work teacher-scholars and students in the field do beyond the classroom, we hope that it represents, at least in thumbnail sketch, the border crossings of DIY activity where the rigid lines between “classroom” and “not-classroom” are intentionally blurred or trespassed.

One increasingly common scene where this occurs is the campus or library makerspace. Maggie Melo, for example, describes turning her first-year writing classroom into a temporary makerspace (“Writing”). Similarly, many library and campus makerspaces are used as ongoing or short-term classrooms for college and university courses, as well as functioning as non-course-related DIY scenes on campuses and in local communities. Chet Breaux argues that these spaces are often urban, inclusive, democratic, and interdisciplinary, offering writing teachers helpful models for maker pedagogies. While makerspaces certainly have the capacity to live up to these ideals, scholars such as Shivers-McNair and Melo have interrogated some of the ways they reproduce social inequalities through cultural rhetorics, discourses, and literacies that determine maker prerogatives and subjectivities, even as their tools are made more widely available. In other words, access in and of itself does not necessarily lead to equality, as these spaces are often white, masculine, and heteronormative. Further, rhetorics of innovation and mediation may very well be complicit in the routine conventions of boundary marking that privilege some makers and acts of making over others (Melo, Shadow 58; Shivers-McNair 3).

As one of us has discovered in opening a library makerspace on their campus, even those that are intended to embody the inclusive, democratic, playful dimensions of DIY can be subject to capitalist impulses. In order for this makerspace to receive ongoing institutional support, it was placed in the university’s administrative structure under the same umbrella as the startup incubator and labs that encourage STEM and business students to develop products that can be brought to market and found the start-ups to sell them. While the makerspace’s initial funding was granted specifically to create a space where non-STEM and non-business majors could experiment, play, and use what they make to satisfy personal and community needs, its place in the university structure means that the space and its equipment are frequently presented to students, faculty, and staff as serving explicitly venture-capitalist, market-driven ends. This is reflected in emails sent by the makerspace (and who is and is not on the distribution for those emails), what gets posted or featured on the makerspace’s website and social media accounts, which majors are most prominently encouraged to get involved in makerspace activities (from attending workshops to being trained as student leads on the tools and machines), and how (and how much) physical space is allocated for different kinds of machinery, tools, and materials.

The work, then, of keeping the makerspace open to other possibilities, to fostering a scene that embraces and practices DIY, to being a scene where students can make something else (community, counterpublics, radical futures), while still being supported with adequate funding, staffing, and other institutional support, requires ongoing labor. Those of us (faculty, staff, and students) who are working to build a DIY scene in the makerspace continue to make do with what is at hand, while teaching and learning creative and critical making.

Figure 3. Entrance to Cal Poly Pomona's Maker Studio: a screen displaying the makerspace's social media, flyers with QR codes, and the studio's name in neon light

What motivates us in these efforts is the possibility of making better futures for our students, communities, and ourselves. This is why we believe DIY to be inseparable from an ethic of social hope.

Taking Leave, Making New

In DIY culture, scenes are typically described as edgy, bohemian, or oppositional, descriptors that do not readily apply to academia. Our scenes are typically immersed in professional and institutional discourses, and they thus seem to endorse all things official, mainstream, and respectable. Yet, as we have shown, certain scholars in our field have brought a DIY sensibility to bear upon our current practices. We observe a DIY motive in the efforts of Ceraso and Pavesich to define DIY learning, Melo’s classroom-turned-makerspace, and Koupf’s work to include DIY tinkering in writing pedagogies. A DIY motive can also be seen in the founding of digital journals that purposefully depart from the standard conventions of scholarly print media, as well as in projects like Jim Ridolfo’s RhetMap (2012) and the many podcasts produced by a new generation of scholars, including This Rhetorical Life, created by graduate students in Syracuse University’s Composition and Cultural Rhetoric program (2012); Eric Detwiler's Rhetoricity (2015); Ames Hawkins and Ryan Trauman’s Masters of Text (2015); Charles Woods’ The Big Rhetorical Podcast (2018); Shane Wood’s Pedagogue (2019); and Wilfredo Flores’ Tell Me More! (2021). Finally, the appearance of campus makerspaces reinforces DIY’s ethos of critical making. The makerspace has the obvious potential to be a scene where a different kind of writing happens, where a different kind of text is literally made.

In closing, then, we want to remind our readers that DIY has had a long association with utopian thinking, but utopian thinking of a certain kind—utopia as neither a blueprint nor some far off vision of fixed perfection, but rather a utopia that can be endlessly rewritten, an “open” utopia, to use the words of cultural historian Stephen Duncombe. Indeed, Duncombe goes so far as to suggest that utopia is best understood as a prompt for future possibilities. Applied to our effort here, this means imagining the ways that DIY composition might yet reveal itself to us.

This is exactly how we would like our readers to think of this article: as a prompt for the exercise of “creative play and collective imagination” (Day vii). For this reason, we invite readers to look for new expressions of a DIY sensibility, new forms of making, and new scenes for rewriting our present understanding of what writing means or, or could mean, from a DIY perspective. As we tried to show here, some of our colleagues have already done so. We hope you will accept our invitation to do likewise.

[1] We especially want to acknowledge the leadership and contributions of Ashley Beardsley, Marilee Brooks-Gillies, Sara Cooper, Megan Heise, Noël Ingram, Danielle Koupf, Kelly McElroy, Chelsea Murdock, Kristin Ravel, Melissa Rogers, Laura Romano, Ann Shivers-McNair, Erica Stone, Martha Webber, Kali Jo Wacker, Kristen Wheaton, and Patrick Williams. Local organizations that provided workshop spaces, instruction, and/or material resources include the Print League of Kansas City, Portland Button Works, Tampa Zine Fest, and Pittsburgh’s Contemporary Craft, as well as the Pittsburgh Center for Creative Reuse. We additionally want to recognize the contributions of workshop participants and Handcrafted Rhetorics SIG meeting attendees. Interested readers can learn more at https://handcraftedrhetorics.org/

[2] There are, of course, additional DIY lineages to trace. In this era, we could look to the collective work of Black communities during Reconstruction and to workers’ movements. Further, in the mid-20th century, the Civil Rights and Black Power, American Indian, Chicano Liberation, and Women’s Movements created plenty of texts, music, and other things themselves. Examples include the Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast for School Children Program and other initiatives; the creation of AIM Patrol to monitor police treatment of Native Americans, the Indian Health Board of Minneapolis, and the occupations of Alcatraz, the Mayflower replica, and other sites; the creation of the National Farm Workers Association and the murals of the Chicano Art Movement; the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective’s workshops and publication of Our Bodies, Ourselves; and the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation (or Jane Collective) and other underground abortion services before Roe v. Wade. The punk music and zine history of DIY that we focus on below is not the only one, but it is one that was explicitly described as DIY at the time. It is also a history that is focused on the production of texts, while the movements summarized here were largely more focused on other dimensions of activism, though they did produce several–and several kinds of–texts. Finally, the punk roots of DIY have been taken up in rhetoric and writing studies, as we discuss below. While this essay is ultimately focused on currents within rhetoric and writing studies, we are very interested in how these often-ignored histories of DIY could be used to alter our understanding of DIY and the field.

[3] It is worth noting, however, that the Arts & Crafts Movement was funded by the accumulation of capital from British (and later, American) colonialism, imperialism, and industrialism. For example, William Morris’s mother came from a wealthy family and his father was a financier, and despite the movement’s ideals, the high-quality items produced by shops like Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., Morris & Co., and Kelmscott Press were often only accessible to those with wealth supported by the British Empire’s military and economic activities.

Adamson, Glenn. The Invention of Craft. Bloomsbury, 2013.

Anderson, Daniel. “Prosumer Approaches to New Media Composition: Consumption and Production in Continuum.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 8, no. 1, 2003, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/8.1/coverweb/anderson/story.html.

Arola, Kristin. “Composing as Culturing: An American Indian Approach to Digital Ethics.” Handbook of Writing, Literacies, and Education in Digital Cultures, edited by Kathy A. Mills, Amy Stornaiuolo, Anna Smith, and Jessica Zacher Pandya, Routledge, 2018, pp. 275–284.

---. “A Land-Based Digital Design Rhetoric.” The Routledge Handbook of Digital Writing and Rhetoric, edited by Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes, Routledge, 2018, pp. 199–213.

Ball, Cheryl, and Colin Charlton. “All Writing is Multimodal.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 42–43.

Beck, Estee. “Discovering Maker Literacies: Tinkering with a Constructionist Approach and Maker Competencies.” Computers and Composition, vol. 58, Dec. 2020, p. 102604. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2020.102604.

---. “Sustaining Critical Literacies in the Digital Information Age: The Rhetoric of Sharing, Prosumerism, and Digital Algorithmic Surveillance.” Social Writing/Social Media: Publics, Presentations, and Pedagogies, edited by Douglas M. Walls and Stephanie Vie, The WAC Clearinghouse and UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 37–52.

Bellwoar, Hannah, and Scarlett Berrones. “The ‘Hatting’ of the Clock: Crafting Juniata’s Knitting Community through Yarn Bombing the Clock Tower.” Harlot: A Revealing Look at the Arts of Persuasion, vol. 14, 2015, https://harlotofthearts.org/ojs-3.3.0-11/index.php/harlot/article/view/309/170.

Bratta, Phil and Malea Powell. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Entering the Cultural Rhetorics Conversations.” enculturation, no. 21, 2016, http://enculturation.net/entering-the-cultural-rhetorics-conversations.

Breaux, Chet. “Why Making?” Computers and Composition, vol. 44, 2017, pp. 27–35.

Carter, Joyce Locke. “2016 CCCC Chair’s Address: Making, Disrupting, Innovating.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 68, no. 2, National Council of Teachers of English, 2016, pp. 378–408.

Ceraso, Steph, and Matthew Pavesich. “Learning as Coordination: Postpedagogy and Design.” enculturation, vol. 28, 3 May 2019, http://enculturation.net/learning_as_coordination.

Cobos, Casie, et al. “Interfacing Cultural Rhetorics: A History and a Call.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 37, no. 2, Routledge, Apr. 2018, pp. 139–154. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/07350198.2018.1424470.

Crowley, Sharon. Composition in the University: Historical and Polemical Essays. U of Pittsburgh P, 1998.

Day, Amber, ed. DIY Utopia: Cultural Imagination and the Remaking of the Possible. Lexington Books, 2016.

Dormer, Peter. The Art of the Maker: Skill and its Meaning in Art, Craft and Design. Thames and Hudson, 1994.

Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Microcosm, 1997.

---. “Opening Up Utopia.” DIY Utopia: Cultural Imagination and the Remaking of the Possible, edited by Amber Day, Lexington Books, 2017, pp. 3–20.

Edenfield, Avery C., and Lehua Ledbetter. “Tactical Technical Communication in Communities: Legitimizing Community-Created User-Generated Instructions.” Proceedings of the 37th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication, 2019, pp. 1–9.

Eichhorn, Kate. Adjusted Margin: Xerography, Art, and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century. The MIT Press, 2016.

Gauntlett, David. Making is Connecting: The Social Meaning of Creativity, from DIY and Knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0. Polity Press, 2011.

Gere, Anne Ruggles. Intimate Practices: Literacy and Cultural Work in U.S. Women’s Clubs, 1880–1920. U of Illinois P, 1997.

Gollihue, Krystin N. “Re-Making the Makerspace: Body, Power, and Identity in Critical Making Practices,” Computers and Composition, vol. 53, Sept. 2019, pp. 21–33. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2019.05.002.

Gruwell, Leigh. Making Matters: Craft, Ethics, and New Materialist Rhetorics. Utah State UP, 2022.

Haas, Angela M. “Making Online Spaces More Native to American Indians: A Digital Diversity Recommendation.” Computers and Composition Online, Fall 2005, http://cconlinejournal.org/Haas/index.htm.

Harley, Ben. “Music against Fascism: DIY Versus the Right Wing Safety Squad.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 2, Routledge, Mar. 2021, pp. 138–151. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/02773945.2021.1877798.

Hawk, Byron. A Counter-History of Composition: Toward Methodologies of Complexity. U of Pittsburgh P, 2007.

Hubbard, Emily. “A Look into the DIY Music Scene that Many Call Home.” The Cougar, 23 Jan. 2019. https://thedailycougar.com/2019/01/23/diy-music-scene/.

Illich, Ivan. Tools for Conviviality. Marion Boyars, 2009 (Rpt).

Kahn-Egan, Seth. “Pedagogy of the Pissed: Punk Pedagogy in the First-Year Writing Classroom.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 49, no. 1, National Council of Teachers of English, 1998, p. 99–104.

Koupf, Danielle. “Proliferating Textual Possibilities: Toward Pedagogies of Critical-Creative Tinkering.” Composition Forum, vol. 35, Association of Teachers of Advanced Composition, 2017. ERIC, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1137815.

Kristofferson, Robert. Craft Capitalism: Craftsworkers and Early Industrialization in Hamilton, Ontario 1840–1872. U of Toronto P, 2007.

Lankshear, Colin, and Michele Knobel, editors. DIY Media: Creating, Sharing and Learning with New Technologies. Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2010.

Lynch, Paul. After Pedagogy: The Experience of Teaching. Conference on College Composition and Communication/National Council of Teachers of English, 2013.

Marcus, Sara. Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. Harper Collins, 2010.

McCullough, Malcolm. Abstracting Craft: The Practiced Digital Hand. MIT P, 1996.

Melo, Marijel Maggie. The Shadow Rhetorics of Innovation: Maker Culture, Gender, and Technology. University of Arizona, 2018. repository.arizona.edu, https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/628032.

---. “Writing is Making: Maker Culture and Embodied Learning in the Composition Classroom.” Digital Rhetoric Collaborative, vol. 8, 2016. https://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2016/03/04/writing-is-making-maker-culture-and-embodied-learning-in-the-composition-classroom/.

Miller, Susan. Textual Carnivals: The Politics of Composition. SIU Press, 1991.

Moon, Tony. “Sideburns” [Zine], Issue 1. London. 1977.

Palmeri, Jason. Remixing Composition: A History of Multimodal Writing Pedagogy. Southern Illinois UP, 2012.

Powell, Malea, et al. “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics.” enculturation, 2014, http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here.

Powell, Malea. “I Got Your Maker Space Right Here: Objects, Things, Making and Relations (Seems Like I’ve Heard This Song Before).” Cultural Rhetorics Conference, 1 Oct. 2016, East Lansing, MI.

Pye, David. The Nature and Art of Workmanship. Cambridge UP, 1968. Excerpt in The Craft Reader, edited by Glenn Adamson. Berg, 2010, pp. 341–353.

Ratto, Matt. “Textual Doppelgangers: Critical Issues in the Study of Technology.” DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media, edited by Matt Ratto and Megan Boler, MIT Press, 2014, pp. 227–236.

Ratto, Matt, and Megan Boler, editors. DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media. MIT Press, 2014.

Risatti, Howard. A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression. U of North Carolina P, 2007.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer. “Cultural Rhetorics and the Digital Humanities: Toward Cultural Reflexivity in Digital Making.” Rhetoric and the Digital Humanities, edited by Jim Ridolfo and William Hart-Davidson, U of Chicago P, 2015, pp. 49–64.

Science Museum. “A Brief History of DIY, from the Shed to the Maker Movement.” 23 Apr. 2020, https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/everyday-wonders/brief-history-diy

Shipka, Jody. Toward A Composition Made Whole. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011.

---. “Evocative Objects: Re-Imaging the Possibilities of Multimodal Composition.” Conference on College Composition and Communication, 13 Mar. 2013, Las Vegas, NV.

---. “On Estate Sales, Archives, and the Matter of Making Things.” Provocations: Reconstructing the Archive, Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP, 2015, https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/reconstructingthearchive/shipka.html

---. “Edible Rhetoric: Making Meals That Matter.” Corridors: The Blue Ridge Writing and Rhetoric Conference, 19 Sept. 2020, Blacksburg, VA.

Shivers-McNair, Ann. Beyond the Makerspace: Making and Relational Rhetorics. U of Michigan P, 2021.

Sinopoli, Carla M. The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India, c.1350–1650. Cambridge UP, 2003.

Sirc, Geoffrey. “Never Mind the Tagmemics, Where’s the Sex Pistols?” College Composition and Communication, vol. 48, no. 1, National Council of Teachers of English, 1997, pp. 9–29. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/358768.

---. “Never Mind the Sex Pistols, Where’s 2Pac?” College Composition and Communication, vol. 49, no. 1, 1998, pp. 104–108. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/358564

Spencer, Amy. DIY: The Rise of Lo-fi Culture. Marion Boyars, 2005.

Warner, Michael. Publics and Counterpublics. Zone Books, 2005.

Wysocki, Anne Frances. “Opening New Media to Writing: Openings & Justifications.” Writing New Media: Theory and Applications for Expanding the Teaching of Composition, edited by Anne Frances Wysocki, Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Cynthia L. Selfe, and Geoffrey Sirc, Utah State UP, 2004, pp. 1–23.