Rich Shivener, York University

Dustin Edwards, University of Central Florida

(Published November 10, 2020)

NOTE: This text works with an online map available at http://arcg.is/0WqTSm and linked below. Readers might wish to check out the article in one tab and the map journal in another.

Digital culture starts in the depths and deep times of the planet. Sadly, this story is most often more obscene than something to be celebrated with awe.

––Jussi Parikka, The Anthrobscene (56)

Scene 1: “Would you like your receipt printed or emailed?” At a coffee shop, the barista waits for our response. We are at the 2018 Watson Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, preparing to discuss some of the initial ideas that led to the foundation of this article. “Email,” one of us replies. With caffeine in hand and a new email notification to be cleared, we move to a nearby table to begin discussing our ideas.

Scene 2: Elsewhere, as a new semester begins, students order our textbooks and access readings through Amazon’s Kindle service, for those e-texts are typically more affordable than their print counterparts. As we overview our syllabi in the fall, we remind students that their projects will be delivered and assessed through our respective learning management systems. “No need for printing copies of your drafts,” we remind them. “All of your work should be submitted digitally.”

Scene 3: We are putting the final touches on this manuscript in real-time over Skype and Google Docs. As we’re talking through what we want to accomplish with our conclusion, we make a few comments on citations we’ve forgotten to add to our Works Cited page. We each agree to make one final read through of the project on our own time, adding suggested edits before we send the manuscript to our editors through email.

Scenes such as these are ubiquitous in a zettabyte era of digital composing. While these scenes saturate our everyday experiences, they also tend to leave few material reminders of their occurrences. A transaction complete, a semester finished, a composing process nearing a state of publication—all examples where digital data are easily archived and retrieved, but also easily forgotten and removed from view. Even so, these scenes are not without their material and ecological effects, as the circulation of new data flows affect environments and bodies, near and far, from our embodied and emplaced locations.

To bring more attention to these elsewhere environments, this article focuses on what we call “the environmental unconscious of digital composing,” a transnational condition dependent on big data infrastructure placed around the world.[1] As many scholars (Hogan; Parikka; Velkova), journalists (Burrington; Glanz), and advocacy groups (McMillan) have articulated, big data comes at a big environmental cost. Showing no signs of slowing anytime soon, a sharp rise in data storage needs can be attributed to rapid increases in mobile phone use, video consumption, device connectivity in the Internet of Things, and online gaming––not to mention article productions like this one. To keep all of this data running smoothly, data centers, which are often built in rural places and employ few people, use massive amounts of water to cool and energy to power their server spaces. That is, data centers consume billions of gallons of water a year (Ristic et al.) and their energy output is equivalent to that of thirty nuclear power plants (Glanz). As a new materialist environmental rhetoric (Clary-Lemon) helps us articulate, data centers are intricately woven with conditions of climate and climate change, an ever-present environmental unconscious that underpins networked life.[2]

Due to data centers’ dispersed locations, carefully crafted messages of environmental stewardship, and acquisition of land and energy through shell companies, their construction by major technology firms rarely receives sustained, in-depth attention from local or national media. Although comprehensive maps of data centers are accessible for public use (Bell), there are few, if any, centralized maps dedicated to understanding the imbrication of data centers and climate change concerns. This article sheds light on such an imbrication by using mapping methods to geolocate data centers from “the big four” technology companies: Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. In effect, we seek to map the basic contours of the environmental unconscious of digital composing. Although necessarily imperfect, partial, and unfinished, our map works to show climate change rhetorics as they manifest in particular data center locations. By visualizing the data center landscape and compiling themes based on an analysis of news articles and company reports, we map and guide readers to see competing rhetorics about climate change in the technology industry. Specifically, we used map data to analyze public texts and discuss six themes related to climate change and data center ecologies (see our “Viewing” section).

We open this article by defining data center ecologies and articulating their consequences through scholarship in digital infrastructure, ecology, and new materialism. Data centers have presented a sort of paradox; such algorithmic powerhouses keep our world connected while threatening ecologies, bodies and their communities, and energies of the planet (Edwards 61). Later, our map design visualizes and discusses competing climate change rhetorics in emergent data center ecologies. Finally, we articulate two ways in which our map—and others yet to be constructed—might be taken up by future scholars and students. Open-access interactive mapping lends itself well to future inquiries and designs about the relationship between digital composing and data center ecologies. In a zettabyte era, the environmental unconscious is at risk of being further muddled as data companies increasingly attempt to paint a greener picture of their environmental impact. We call for researchers to continually map such companies’ environmental impact on local ecosystems through public humanities projects.

Unearthing the Environmental Unconscious of Digital Composing

Rhetorical theory has increasingly accounted for the material, embodied, ecological, and infrastructural dimensions of digital writing and rhetoric (e.g., Boyle et al.; Haas; Micciche; Rhodes and Alexander). Such work has only intensified with the proliferation of wearable devices (e.g., Gouge and Jones; Tham), augmented reality (e.g., Jones and Greene), smart cities (Frith), and ubiquitous and physical computing (e.g., Rieder). Crucially, as Casey Boyle, Jim Brown, and Steph Ceraso argue, “the digital” can no longer be understood as a specific area of concern for rhetorical activity happening on screen-based personal computers (252). The digital, Boyle et al. remind, is an ambient condition: it saturates everyday experiences and informs rhetorical activity in ways that often are not consciously registered. As our opening narratives demonstrate, the digital permeates whole scenes of life—from discursive exchanges online, of course, but also to emplaced and embodied encounters where tactile reminders of large-scale digital infrastructures are disappearing. In other words, in a world where digital data is rapidly expanding because of a proliferation of wireless sensors and devices, the deeper materialities of its infrastructure—reminders of the scale and power of its connectivity—are largely fading from view. To put it differently, as Joanna Zylinska argues, the aesthetics of digital connectivity today look much different than they did a decade ago. Our writing spaces are no longer encumbered by wires and cables—or, if they are, the material reminders are made to be as minimal and clean as possible.

Although cables may be disappearing from domestic and office settings, the wireless, always-on, and ambient conditions of the digital have an immense material footprint. Only, that footprint is not visible for most: tucked underground, undersea, and in window-less storage facilities across the world, a growing network of cables stretch around the planet in strategic configurations that are largely overlaid on top of older communication technology networks, thus mirroring routes of imperialism that amount to what Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias call the “Cloud Empire” (45). As Nicole Starosielski notes, the precursor to today’s cloud network—the telegraph—relied on Indigenous labor and their knowledge of particular lands for the construction of British-controlled “cable colonies” (The Undersea Network 99). Today, big tech firms such as Facebook and Google finance fiber-optic cables that link up to another kind of infrastructure that we examine in this article: data centers. Though they vary in scale, the millions of data centers placed all over the world share a number of characteristics. Large-scale data centers span the size of multiple football fields, require relatively few human workers for their operation, thrive in rural areas where they are provided with cheap land, energy, and tax incentives, and demand vast amounts of energy to power and water to cool their server spaces. And like cables, many data centers are in nondescript and secret locations, such as retrofitted military complexes from the Cold War (see Hu’s research on “data bunkers”).

In line with these shared characteristics, data centers are deeply entangled with their emplaced environments, creating data center ecologies. When building the multimillion-dollar data centers that traffic the world’s zettabytes of data, technology companies keep in mind questions of climate (can cool air be used to neutralize server heat?), existing infrastructure (is there already access to fiber optic cable networks?), and local politics (are there incentives to invest in this place?). Environmental media scholar Mél Hogan figures this interplay among nature, culture, and technology as “Big Data ecologies,” which frames big data as operating within a web of place-based relationships. Similar to arguments in rhetoric and composition that critique metaphorical treatments of ecology, Hogan refigures a techno-ecological understanding of big data to draw attention to big tech’s claims to land, water, and energy. Building on Hogan’s work, our term “data center ecologies” places more emphasis on physical structures and regions in which data centers operate; it encourages us to focus on specific data center sites while also investigating big tech’s global implications.

Our often-unacknowledged reliance on data center ecologies is a key example of what we call the environmental unconscious of digital composing. We use this phrase to explain, on the one hand, how the very possibility of digital composing relies on environmental factors (land, water, climate, availability of energy, etc.), and, on the other hand, how these factors do not readily come to mind when we use digital tools, devices, and platforms. Our formulation of the environmental unconscious of digital composing echoes earlier work attempting to register what has been called the technological unconscious. For example, Nigel Thrift, working from Patricia Clough, discusses how software is part of a technological unconscious, a “sustaining presence which we cannot access but which clearly has effects, a technical substrate of meaning and activity” (156). Our use of the term “environmental unconscious of digital composing” extends in a similar fashion but with particular attention to environmental effects. From our perspective, the environmental unconscious of digital composing cannot be conclusively exposed in any given case: knowing precisely how and where data travel cannot be pinned down once and for all. Understanding how data travel—e.g., “mapping the cloud”—involves complex “material, technological, and entrepreneurial arrangements,” layers of network topology that have been constructed in a piecemeal manner by telecommunications companies and Internet Service Providers as data traffic continues to increase (Holt and Vonderau 85).

Although indeterminacy is a central feature of the digital landscape, we nevertheless situate the environmental unconscious of digital composing as a provocation to remind us that our work in rhetoric and writing studies is never too far removed from environmental crisis. The very conditions of digital rhetoric and writing are intricately woven into the epoch many are calling the Anthropocene, the contested name used to describe an age of environmental change and transformation. If public-facing corporate documents are any indication, data companies are well aware of their environmental impact. In response to the sharp increase of data storage as well as more public scrutiny over their energy consumption, many of the big technology companies have directly written themselves into climate change narratives. Casting themselves in a positive light, big tech has made commitments toward renewable energy by constructing projects that add clean energy to local power grids and investing in more efficient server room design. As Hogan argues, data companies are increasingly fashioning themselves as stewards of the natural environment and writing their own climate change narratives that suggest they offer a “techno-fix” (Haraway) for the climate crisis.

Contrary to these narratives, we have elected to understand the environmental unconscious of digital composing through what Jennifer Clary-Lemon calls a new materialist environmental rhetoric. Clary-Lemon’s articulation of a new materialist environmental rhetoric is supported by interviews with industrial tree planters, as well as scholarship in new materialism, affect studies, and Indigenous philosophies. Noting how human and nonhuman interactions manifested in tree planting narratives, Clary-Lemon troubles logics of efficiency and humanism that so often dominate the work of tree planting. Instead, she articulates three premises of a new materialist environmental rhetoric: “(1) that we need not depend only on logos to define a rhetorical way of being in the world, (2) that there is an ‘underivable rhetoricity’ [Diane Davis’s term] that unites human and nonhuman bodies, and (3) that we understand bodies as sets of relations” (19). Taken together, a new materialist environmental rhetoric is located not in the logos-driven actions of any one body but in the often pre-linguistic relations that emerge between and among bodies.

While Clary-Lemon’s attention is focused on much different landscapes, we follow Clary-Lemon so as to be better attuned to how bodies of all kinds (land, water, non/human) are entangled in data center ecologies. Such an understanding calls us not only to examine how human discourse shapes rhetorical meaning making about data centers, but how particular place-based ecologies are in constant relational—and thus rhetorical—flux. This perspective complicates any sustainable facade data companies may try to project; regardless of their commitment to renewable energy sources, data centers are always imbricated in the complex ecologies in which they are placed and operate. Considering data center ecologies from a new materialist environmental rhetoric perspective would not presume distinct separations between data center and environment (as data companies would have it). Instead of positioning data centers as separate entities that either control or fade into the background of their emplaced environments, we advocate for a more relational understanding that maps the particulars of how climate, environment, and infrastructure are more accurately entangled.

What this framework means, then, is that something like responsibility for the environmental unconscious of data center ecologies is not easily pinpointed. A new materialist environmental rhetoric occasions us to recognize that critique alone will not get us out of what many are calling the sixth great extinction. In the final chapter of Planting the Anthropocene, Clary-Lemon figures new materialist environmental rhetoric through Donna Haraway’s call of “staying with the trouble,” which is an ongoing commitment to threading stories about ongoingness and possible recuperation in the Anthropocene. From this perspective, a new materialist environmental rhetoric is a call to “listen better” to the environmental trouble in which we find ourselves dwelling (Clary-Lemon 168). Likewise, as Nathaniel Rivers explains, it would be a mistake to fall into a fantasy of imagining environments free from human impact. Working with the ever-present trope of the footprint in environmental discourses, Rivers suggests that human footprints are inevitable and necessary: to dwell with the damage of human footprints is not to imagine a world without human disturbance, but rather, is to acknowledge a world where disturbances are expected but better cared for and made more relationally meaningful.

While a new materialist environmental rhetoric has been productive in accounting for data center ecologies, we also acknowledge ongoing and important criticisms of various new materialisms (and other allied bodies of knowledge such as posthumanism and affect studies). Particularly, Indigenous scholars such as Kristin Arola, Kim TallBear, and Zoe Todd have pointed out the erasure of knowledge systems and cosmologies that have long accounted for the more-than-human. Further, Black Studies scholars such as Tiffany Lethabo King, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, and Armond Towns have discussed how practices of white supremacy have violently indexed the very parameters of who qualifies as human, subhuman, inhuman, and so on. In short, new materialism does a pretty bad job at accounting for race and racism (Leong)—and its theorization and uptake has the potential of further perpetuating colonial and white supremacist modes of scholarly thought (Todd).

Recently, scholars in rhetoric and writing studies—including a Rhetoric Review forum on the intersections between posthumanism and cultural rhetorics edited by Donnie Johnson Sackey and more recent work from Jennifer Clary-Lemon (“Gifts”)—have unpacked some of these critiques and pointed out possible paths for future work. For us, these critiques have been important for our consideration of data center ecologies and the environmental unconscious of digital composing. Given that our work concerns questions of land, water, and histories of emplaced environments in relation to digital infrastructures, we have found it crucial to engage how data center ecologies are entangled with (settler) colonial strategies of expansion, control, and dominance. As Diana Leong concludes in an essay demonstrating the limits of (white) new materialism in the context of Black Lives Matter,

my objective is not to reject wholesale the new materialisms. Their attempts to offer a broader theorization of matter and being are appropriate and necessary for our techno-scientific age. Indeed, a planetary crisis requires a more expansive philosophy. What I am suggesting instead is that challenges to human exceptionalism should proceed through a critique of race, or we risk reorganizing old privileges (“All Lives”) under new standards of being (“Matter”). (24)

Similar to Leong, we want to work with a version of new materialism capable of contending with how race and racialized violence are embedded in the data center ecologies with which we are entangled.[3]

Our mapping, as we turn to next, is a response to the environmental unconscious of digital composing. It is not meant to be an outside critique of the data center landscape, but a more messy and embedded response that calls us—and others—to continue to listen better to the environmental trouble of data center ecologies.

Visualizing the Environmental Unconscious: Methods for Composing a Map Journal

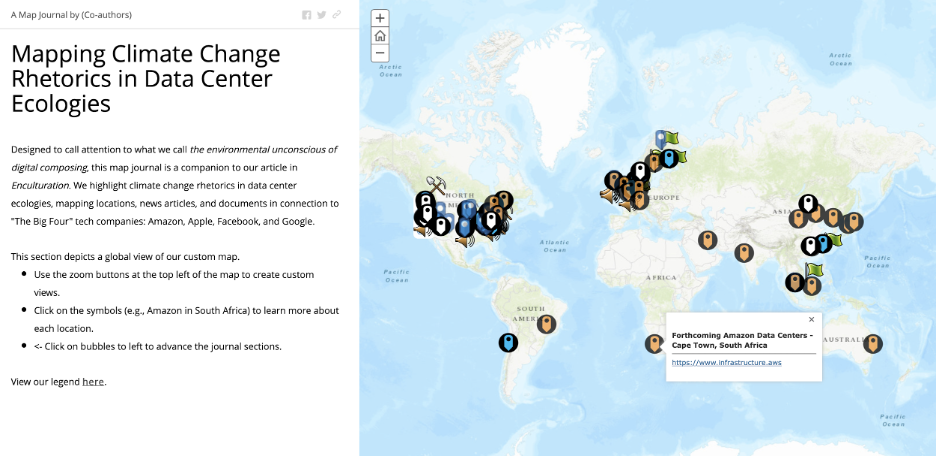

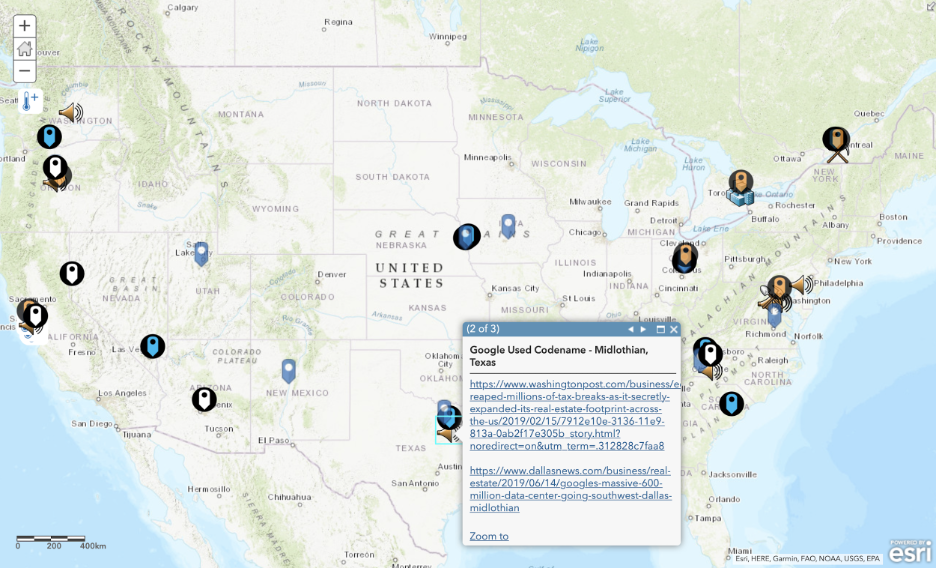

To foreground the environmental unconscious of digital composing, we enacted mapping methods to geolocate climate change rhetorics as well as data centers from “the big four” technology companies: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. This section discusses the methods behind our companion map journal titled “Mapping Climate Change Rhetorics in Data Center Ecologies” (Fig. 1) We also introduce the original map in which we entered our data (Fig. 2). To begin, we geolocated the big four’s data center ecologies across the world. At the time of writing this article, Amazon had twenty-two data center locations; Apple, five; Facebook, fifteen; and Google, sixteen.[4] For additional context, we mapped some data center ecologies of Microsoft, large third-party (colocation) data center companies (e.g., Equinix and Digital Realty) and start-ups companies. Again, we use the term “data center ecologies” because such locations are always imbricated in the complex ecologies in which they are placed and operate.

After mapping data center ecologies, we searched and geo-located climate change rhetorics emerging in proximity to data centers. For this article, we coded climate change rhetorics as public texts that encompass intersections of data center activity and climate-related concerns, which include company reports and news articles on so-called “green data centers,” environmental activism, secret expansions in rural regions, and renewable energies, to name a few topics. Our intent is to help viewers see climate change rhetorics in proximity to data centers––and to see and learn more about hotbeds of competing rhetorics from publics and companies in data center ecologies. To guide viewers in our map journal, we read each rhetorical text closely for their topics and primary concerns, later grouping them under emergent themes in relation to climate change. From a global view, the map journal serves as a visual bibliography of and thematic guide to a tense rhetorical landscape, one in which rhetorics of natural resources, communities, and data infrastructures constitute complex ecologies. In such a landscape, for example, activists in Virginia argue that technology companies exhaust coal, electricity, and water in rural areas (McMillan), but companies such as Google and Apple insist that data centers create jobs and opportunities for renewable energy. Our hope is that viewers will interact with such rhetorics when they survey the landscape.

For scholars of rhetoric and media, interactive maps have been evocative resources for framing global topics such as viral icons, death, networked communication and citizenship. As April Conway and her students demonstrated by visualizing summer travel, interactive mapping helps authors “explore intercultural learning, digital tools, creative and civic possibilities of spatial representation, and diverse practices of writing” (“Teaching Statement for Digital Mapping Possibilities Assignment”). Maps by recent scholars of public rhetoric and media support such a claim. IIn a follow-up to Still Life with Rhetoric, Laurie Gries’s “Mapping Obama Hope” visualizes the circulation and transformation of Shepard Fairey's Obama Hope image and viral icons using Google and actor-network maps. Jason Crider and Kenny Anderson’s “Disney Death Tour” maps news articles of patrons who died across the park, claiming that “it functions as a writing, as opposed to another reading, and offers an emplaced critique as a means of creating civic opportunities for rewriting corporate space” (“Introduction”). More globally, James Bridle and Nat Buckley’s Citizen Ex web browser extension tracks where your data circulates in the world (e.g., reading a BBC article connects you to the United Kingdom as well as China). Offering a nonhuman perspective, Nicole Starosiekski, Erik Loyer, and Shane Brennan’s “Surfacing” map invites users to travel like a signal node across the world's undersea networks of cables that power our seemingly wireless lives. Such maps are useful examples because they do not guide reader-viewers, but rather invite them to explore rhetorical terrains, “to collect, process, analyze, and visualize data in ways that are conducive for producing individual insight and collective knowledge” (Gries). Their arguments are constructed through an individual’s navigation rather than a composer’s series of linear paragraphs.

Reflecting the aims of the aforementioned projects, our digital map is powered by Esri StoryMaps (Fig. 1) and ArcGIS Online mapping interface (Fig. 2). Esri StoryMaps and ArcGIS Online are mapping resources that require no coding for the writer-designer. Although our approach lacks rhetorical prowess like Crider’s and Anderson’s map design through Leaflet, it is an accessible resource, for future writer-designers can copy and build on ArcGIS Online-powered public maps (including ours). This accessibility is important for our goal of creating an interactive research and pedagogical tool for writing studies scholars and students interested in climate change rhetorics. Reflecting Clary-Lemon’s call to “listen better,” our intent here is to be conditional and invitational, for climate change rhetorics in data center ecologies will continue to grow indefinitely.

Viewing the Map Journal and its Six Themes

Figure 1 is a link to our map journal composed in Esri StoryMaps. As we note in our methods section, the map journal is a result of geo-locating and analyzing public texts in proximity, and in relation to, data centers and climate change. Our findings are grouped into six themes and presented as follows:

- Regional redirections: how data center construction and expansion is nestled in both rural and urban regions of the world;

- Planned protests: how data center consumption has been challenged by particular citizens and advocacy groups;

- Climate control: how the data center industry has worked to temper climate concerns by building “green” data centers and investing in renewable energy;

- Secrets and security: how the exact operations of data centers—from acquiring land and water rights to energy/water consumption totals—are often kept from public view;

- Expanding empire: how technology companies are increasingly expanding their infrastructural footprints by buying land and securing water rights; and

- Elsewhere excavations: how data center mapping projects such as ours leave open room for future research and inquiry.

Fig. 1: ig. 1: The authors’ findings in an embedded map journal, available in full view at http://arcg.is/0WqTSm. A PDF version is also available here.

This screenshot contains two parts: on the left, it shows an introduction page of our map journal, discussing how to navigate the text; on the right, it shows also a global map of North America, South America, Africa, Europe, Asia and Australia and data points in green, orange, blue, white, and green.

Fig. 2: A screenshot of an embedded interactive map, available in full view at http://arcg.is/15i4i0.

This screenshot shows a map of the United States that is redacted with data points on the big four technology companies: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. Data points are colored in green, orange, blue, white, and green. A data point call-out box reads “Google Used Codename - Midlothian, Texas” and links to articles in The Washington Post and Dallas News.

Toward Moments of Environmental Consciousness

As our map shows, technology companies, residents, and more-than-human bodies (water, energy, land, material infrastructures, etc.) are entangled in a complex rhetorical landscape—literally. These landscapes implicate us in different ways—but in ways that matter—in local and planetary conditions of climate change. From our new materialist perspective, combined with mapping climate change rhetorics in data center ecologies, our work is designed to raise awareness––or consciousness––about the relationship between particular environments and digital composing. Although the mapping approach, on its surface, works from a satellite view, we have found that a more visceral experience occurs when dwelling with the particulars of data center ecologies. We hope that our map encourages further response and prompts different ways of opening up and relating to the data center ecologies in which we find ourselves entangled. We close, then, by describing two ways in which scholars and students might build on our project: (1) closer ethnographic research with communities and more-than-human life near particular data centers and (2) the making of other digital projects to better listen to the environmental unconscious of digital composing.

A cursory view of our map reveals a satellite view of the environmental unconscious, but we believe more intimate noticing is needed. By taking a deeper dive into news articles and reports, we can see that Google, Facebook, and other companies are reaching agreements with local utility companies and governments, sometimes behind closed doors and codenames (Neibauer). Put differently, the big four use a range of public and secret methods to further build their cloud empires where wind, water, land, and electricity are exploited to add further capacity to growing data storage needs.

Although our research yielded a score of articles and reports on American and European protests and commentary about data center constructions, we know little about the ways in which data centers are affecting communities once they are in full operation. Google, for instance, says it has “invested almost €3.4 million in grants to initiatives in our data center communities that build the local skills base—like curriculum and coding programs, as well as educational support through teaching collaborations at area colleges” (“Fredericia, Denmark”). Researchers might visit data center ecologies to assess, on the ground level, ways that massive data centers impact writing and cultural activities. Further, researchers might learn from community activists who have effectively organized to challenge land and energy impositions. How have local activists raised consciousness about such issues? What strategies are effective for confronting data center expansions and claims to techno-optimism? How can researchers tell such human-centered stories while also engaging in multi-species storytelling to listen better to how more-than-human bodies are likewise affected by data center ecologies?

In addition to more ethnographic research in particular data center ecologies, we believe more work can be done with mapping and other digital projects. When reflecting on our work here, we acknowledge that any map has biases. What have we missed, over-emphasized, or misconstrued? As Amy Propen argues in Locating Visual-Material Rhetorics: The Map, the Mill, the GPS, maps are “partial, selective representations of the world; they are always in flux and respond to their shifting contexts and relations” (11). Our map is not a complete resource, but rather a beginning, an invitation to critique and transform maps as imagined through other lenses unlike our own. New maps by scholars, teachers, and students would amplify Propen’s view––with which we align––that “maps constitute versions of contested, rhetorical space” (Locating 194). As noted in our map journal, Microsoft and colocation companies (Digital Realty, Equinix) are very much involved in data center ecologies, but we chose to pilot this project with the big four. And as we note above, so too are local communities. Future maps might function as “rhetorical advocacy tools that can represent groups that might not otherwise have representation in the [climate change] debate” (Propen Locating 194).

Other digital projects might further bring to light the environmental unconscious of digital composing, provoking more active opportunities for citizens to confront their own relationship with data center ecologies. For instance, there is room to further amplify Bridle and Buckley’s Citizen Ex browser extension to map, in a user-specific way, where one’s data travel after logging hours of searching the web. Citizen Ex, designed to provoke questions about how data are being used to map individual users’ citizenship profiles, can also provoke questions about where and why data travel to particular locations. We imagine other interactive projects—where the places of the digital are brought into rich, relational view—might help forge more room for rhetorical invention in the face of accelerated environmental damage.

Our project and such future inquiries are ways to stay involved in the conditions of climate change––to remind ourselves of the role we play in it. We are not arguing for a withdrawal of digital composing through data center companies. Indeed, these composing technologies were necessary to complete this very article. We brainstormed over Microsoft Skype, collaborated on Google Docs, messaged random ideas in Apple’s iMessage app, all while realizing our data are coursing through the energies of the planet. In a manner that echoes Haraway’s directive to “stay with the trouble,” staying implicated—avoiding positions of detached purity or apocalyptic assuredness—is one way to work through the uneven conditions of the Anthropocene. For us, it has been a visceral experience to plot dimensions of an always in-flux environmental unconscious of digital composing, to geolocate particular points of contact and put ourselves in relation with the many elsewhere places that power our digital lives. Although advocating for more oversight with regard to big tech companies is one direction we can and should take, we might also continue to make public digital humanities projects that may have a chance at increasing individual sensitivities and heightening collective urgencies for working through conditions of climate (in)justice.[5]

[1] For Donna Strickland, the managerial unconscious of writing studies “is a discursive one, something unspoken in the most prominent texts in the field even as the people writing the texts may be holding administrative positions” (3). She unearths the gendered inequities and emotional labor that lurk beneath field documents, conferences, and texts. For us, the environmental unconscious has emerged as a critical keyword for considering how climate change is deeply entangled with digital rhetoric and writing.

[2] Though we focus on the effects of data centers in this article, our discussion of the environmental unconscious of digital composing aligns with work in electronic waste and planned obsolescence (see, for example, Johnson; Madden).

[3] There is much more to say about citational politics here, and about how, if at all, new materialism might work in alliance with bodies of knowledge that, as Zoe Todd notes, are often erased by the “Great Thinker[s]…on the public speaking circuit these days” (19). While perspectives range on how to do this work or if at all (e.g., Tiffany Lethabo King notes the value of decolonial refusal and abolitionist skepticism), existing scholarship has provided some perspectives on how to engage these dicussions with greater care, respect, and humility (e.g., Arola; Clary-Lemon [“Gifts”]; Sackey; Todd).

[4] Many locations have more than one data center. For example, Amazon has “regions,” which might contain three or more data centers.

[5] For the sake of brevity, our Works Cited below does not include entries from company sites and news articles in our web map and map journal. However, these sources are linked in the map.

Arola, Kristin. “My Pink Powwow Shawl, Relationality, and Posthumanism.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 38, no. 4, 2019, pp. 386–90.

Bell, Eric. Baxtel, 2020, https://baxtel.com.

Boyle, Casey, et al. “The Digital: Rhetoric Behind and Beyond the Screen.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 3, 2018, pp. 251-59.

Bridle, James, and Nat Buckley. Citizen-Ex, 2015, citizen-ex.com.

Burrington, Ingrid. “The Environmental Toll of a Netflix Binge.” The Atlantic, 16 Dec. 2015, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/12/there-are-no-clean-clouds/420744/.

Clary-Lemon, Jennifer. “Gifts, Ancestors, and Relations: Notes toward an Indigenous New Materialism.” Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing and Culture, no. 30, 2019, http://enculturation.net/gifts_ancestors_and_relations.

---. Planting the Anthropocene: Rhetorics of Natureculture. Utah State UP, 2019.

Clough, Patricia Ticineto. Autoaffection: Unconscious Thought in the Age of Teletechnology. U of Minnesota P, 2000.

Conway, April. “Teaching Statement for Digital Mapping Possibilities Assignment.” Queen City Writers, vol. 6, no. 1-2, 2018, qc-writers.com/2018/05/31/1279.

Couldry, Nick, and Ulises A. Mejias. The Costs of Connection: How Data is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Stanford UP, 2019.

Crider, Jason, and Kenny Anderson. “Disney Death Tour: Monumentality, Augmented Reality, and Digital Rhetoric.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 2, no. 23, 2019, kairos.technorhetoric.net/23.2/topoi/crider-anderson/index.html.

Edwards, Dustin. “Digital Rhetoric on a Damaged Planet: Storying Digital Damage as Inventive Response to the Anthropocene.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 39, no. 1, 2020, pp. 59-72.

“Fredericia, Denmark.” Google, www.google.com/about/datacenters/inside/locations/fredericia/community-outreach.html.

Frith, Jordan. “Big Data, Technical Communication, and the Smart City.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 31, no. 2, 2017, pp. 168-187.

Glanz, James. “Power, Pollution, and the Internet.” The New York Times, 22 Sept. 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/09/23/technology/data-centers-waste-vast-amounts-of-energy-belying-industry-image.html.

Google. A Circular Google. Google, June 2019, services.google.com/fh/files/misc/circular-google.pdf.

Gouge, Catherine, and John Jones. “Wearables, Wearing, and the Rhetorics that Attend to Them.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 3, no. 46, 2016, pp. 199-206.

Gries, Laurie. “Mapping Obama Hope: A Data Visualization Project for Visual Rhetorics.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 2, no. 21, 2017, kairos.technorhetoric.net/21.2/topoi/gries/index.html.

Haas, Angela M. “Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice.” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 4, no. 19, 2007, pp. 77-100.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke UP, 2016.

Hogan, Mél. “Big Data Ecologies.” Ephemera, vol. 18, no. 3, 2018, pp. 631-657.

Holt, Jennifer, and Patrick Vonderau. “Where the Internet Lives: Data Centers as Cloud Infrastructure.” Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructure, edited by Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, U of Illinois P, 2015, pp. 71-93.

Hu, Tung-Hui. A Prehistory of the Cloud. MIT P, 2015.

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman. “Animal: New Directions in the Theorization of Race and Posthumanism.” Feminist Studies, edited by Kalpana Rahita Seshadri et al., vol. 39, no. 3, 2013, pp. 669–85.

Johnson, Meredith Zoetewey. “Green Lab: Designing Environmentally Sustainable Computer Classrooms during Economic Downturns.” Computers and Composition, no. 34, 2014, pp. 1-10.

Jones, Madison, and Jacob Greene. “Augmented Vélorutionaries: Digital Rhetoric, Memorials, and Public Discourse.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 22, no. 2, 2018, kairos.technorhetoric.net/22.1/topoi/jones-greene/index.html.

King, Tiffany Lethabo. “Humans Involved: Lurking in the Lines of Posthumanist Fight.” Critical Ethnic Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2017, pp. 162–85.

Leong, Diana. “The Mattering of Black Lives: Octavia Butler’s Hyperempathy and the Promise of the New Materialisms.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, vol. 2, no. 2, Sept. 2016, pp. 1–35. catalystjournal.org, doi:10.28968/cftt.v2i2.28799.

Madden, Shannon. “Obsolescence in/of Digital Writing Studies.” Computers and Composition, no. 33, 2014, pp. 29-39.

McMillan, Robert. “Apple and Greenpeace Trade Blows in Data Center Grudge Match.” Wired, 19 Apr. 2012, www.wired.com/2012/04/apple-and-greenpeace.

Micciche, Laura. “Writing Material.” College English, vol. 76, no. 6, 2014, pp. 488505.

Neibauer, Michael. “Code Name Kale: How the Data Center World is Keeping its Loudoun Projects a Secret.” Washington Business Journal, 18 April 2018, www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2018/04/18/code-name-kale-how-the-data-center-world-is.html.

Parikka, Jussi. A Geology of Media. U of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Propen, Amy. Locating Visual-Material Rhetorics: The Map, the Mill, and the GPS. Parlor P, 2012.

“Renewable Energy.” Google, www.google.com/about/datacenters/renewable.

Rhodes, Jacqueline, and Jonathan Alexander. Techne: Queer Meditations on Writing the Self. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State UP, 2015.

Rieder, David. Suasive Iterations: Rhetoric, Writing, and Physical Computing. Parlor P, 2017.

Ríos, Gabriela R. “Cultivating Land-Based Literacies and Rhetorics.” Literacy in Composition Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015, pp. 60-70.

Ristic, Bora, et al. “The Water Footprint of Data Centers.” Sustainability, vol. 7, no. 8, 2015, pp. 11260-11284.

Rivers, Nathaniel. “Deep Ambivalence and Wild Objects: Toward a Strange Environmental Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 45, no. 5, 2015, pp. 420-40.

Sackey, Donnie Johnson. “Perspectives on Cultural and Posthuman Rhetorics.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 38, no. 4, 2019, pp. 375–77.

Starosielski, Nicole. The Undersea Network. Duke UP, 2015.

---, et al. “Surfacing.” www.surfacing.in/?image=tungku-brunei-cable-station.

Strickland, Donna. The Managerial Unconscious in the History of Composition Studies. SIUP, 2011.

TallBear, Kim. “An Indigenous Reflection on Working beyond the Human/Not Human.” GLQ:A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 21, no. 2–3, 2015, pp. 230–35.

Tham, Jason Chew Kit. “Interactivity in an Age of Immersive Media: Seven Dimensions for Wearable Technology, Internet of Things, and Technical Communication.” Technical Communication, vol. 65, no. 1, 2018, pp. 46-65.

Thrift, Nigel. Knowing Capitalism. Sage, 2005.

Todd, Zoe. “An Indigenous Feminist’s Take On The Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just Another Word For Colonialism.” Journal of Historical Sociology, vol. 29, no. 1, 2016, pp. 4–22.

Towns, Armond R. “Black ‘Matter’ Lives.” Women’s Studies in Communication, vol. 41, no. 4, Oct. 2018, pp. 349–58. doi:10.1080/07491409.2018.1551985.

Velkova, Julia. “Data That Warms: Waste Heat, Infrastructural Convergence, and the Computation Traffic Commodity.” Big Data & Society, vol. 3, no. 2, 2016, pp. 1-10.

Zylinska, Joanna. Nonhuman Photography. MIT P, 2017.