Kathryn Trauth Taylor, Purdue University

Enculturation: http://www.enculturation.net/naming-affrilachia

(Published June 21, 2011)

For decades, the voices of African Americans within Appalachia went unacknowledged. Perceptions of the region’s diversity were limited by stereotypes that portrayed Appalachians as mountain dwellers who were primarily white. In response to a long history of exclusion, African American and Appalachian poet Frank X Walker created the term Affrilachian in 1991 to name African Americans who considered themselves part of Appalachia but who were not accounted for in traditional, albeit stereotypical, understandings of the region. Since then, Walker has published five books of poetry; served as editor of the first journal of Affrilachian Art & Culture (Pluck!); founded the group called Affrilachian Poets; helped create the first video documentary of Affrilachia, Coal Black Voices in 2001; and inspired such advancements as a Journal of Appalachian Studies special issue on race in 2004.1

Today, twenty years after the term’s creation, Affrilachian art designates an entire scene of poetry, fiction, music, and film emerging from communities of African American Appalachians both with and beyond the geographic boundaries of Appalachia.

Despite these major changes to Appalachian scholarship and the growing number of Affrilachian artists, few academic writers have considered the power of their rhetoric to transform historical understandings of Appalachian identity and shape the paths of future research on the region. As Affrilachian artists act from multiple minority positions, their acts become rhetorical - inspiring other unique Appalachian identity-performances and creating an ecological scene of rhetorical influence. My aim here is to explore how Walker and other Affrilachian artists catalyze performative scenes of rhetorical influence that create new, more comprehensive conceptions of Appalachian identity and experience. By describing these scenes as performative rhetorical ecologies, I hope to emphasize the importance of performance - especially of repeatable, influential acts of naming and identification - in generating diverse, interconnected scenes, or ecologies that call us to reconceive our historical understandings of Appalachia. Drawing on postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha and rhetorical theorist Jenny Edbauer Rice, I offer the framework of performative rhetorical ecologies as a way of recognizing, conceiving, and valuing groups who live within the liminal, or “in-between” spaces of culture. Though I will draw on the work of other Affrilachian poets, my attention here is devoted mostly to the work of Frank X Walker, whose poetry was the first to name and disseminate black voices as uniquely Affrilachian. My overall goal is to understand how performative rhetorics form liminal groups - specifically those of Affrilachian artists - contest and extend traditional historical narratives, calling us to revise our ways of defining, categorizing, and supporting groups with diverse, yet shared identities.

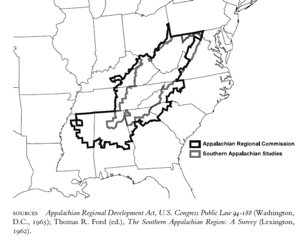

Figure 1: Geographic boundaries of Appalachia as

defined by both the ARC and SAS in 1950-60s (Alexander 228)

One challenge of conjuring Appalachian identity lies in the façade of the mountains, which attempt to demarcate the physical separation of Appalachia from the rest of the United States. Yet despite this material border, a precise definition of “where Appalachia begins and ends geographically” (Higgs xi) has long been debated. The first two major geographic definitions differ considerably from each other. The boundaries defined in 1965 by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) are far broader than those defined in the 1950s by the Southern Appalachian Studies Group (SAS, see Figure 1). Today, the ARC’s updated map (see Figure 2) is the most commonly cited geographic representation of the region, since it is government-sponsored and frequently revised. Appalachian writers like James Still and Frank X Walker, however, recognize that these definitions exist as mythical boundaries that don’t accommodate the nuances of self- and regional-identification with Appalachian culture or the region’s vast history of out-migration.2

Figure 2: Geographic boundaries of Appalachia

(including counties) as defined today by the ARC.

Detailed map available online.

In his One South: An Ethnic Approach to Regional Culture (1982), John Shelton Reed argues that members of a regional community share more than geographic space; “they share a common identity, a common history that binds them together as a people” (Eller 27). American sociologist Robert Bellah defines a community as a group which retains a “community of memory” (153). From these perspectives, communities are created through memories, recollected and retold through time. For Appalachia, these collective memories are often harsh and exaggerated. The stereotype of the “hill-billie” for example, first appeared in print in 1900 when New York Journal used the term to describe “a free and untrammelled white citizen of Alabama, who lives in the hills, has no means to speak of, dresses as he can, talks as he pleases, drinks whiskey when he gets it, and fires off his revolver as the fancy takes him” (“Celebrating”). Over 100 years later, Appalachians still face these harsh stereotypes, most especially from outsiders.

Dialectologist James Robert Reese contends that mountaineers are perceived by non-Appalachians not as “actual people who reside in the same world,” but as “mythic personages who represent a way of life incompatible with the essential, rational, everyday mode of behavior” exhibited by those in the mainstream (494). Even Rhetoric and Composition scholars trained in a post-colonial, post-"Students Right to Their Own Language" era fall prey to this notion.3 Kathy Sohn begins her Whistlin’ and Crowin’ Women of Appalachia (2006), for example, by recalling a moment at the 1994 Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) in Nashville when two scholars mimicked their server’s southern dialect and then launched into a few redneck jokes (1). These hyperbolized, mythical conceptions of Appalachians are frequently attributed to the region’s geography: the vast mountain ranges that both enclose and close off the region from “mainstream” culture contribute to conceptions of Appalachians as “untrammelled” and uncontrollable, cut-off and irresponsible. From the beginnings of scholarship on the region, writers acknowledged that these traditional stereotypes position Appalachians as Others mostly misunderstood and misrepresented (Allison; Bennett; Hartigan; Higgs; Purcell-Gates; Sohn; Turner and Cabbell). Victor Villanueva has even said that “Appalachian is a color” in the sense that the group is prone to stereotypical representations that verge on racism (xiv).4

For African Americans of Appalachia, this Otherness is folded doubly back onto itself.5 In the first published collection on this topic - Blacks in Appalachia (1985) - the group is called a “racial minority within a cultural minority” (Turner and Cabbell, eds. xix).6 Post-colonial theorist Homi Bhabha names the space of double minority a “hybrid site of cultural negotiation” (178). In The Location of Culture(2004), Bhabha claims that people who live in the liminal spaces between cultures are in a unique position to build their own identities through present-tense performances - or lived moments that arise from immediate, raw experiences. It is through such performance that “objectified others may be turned into subjects of their history and experience” (178), and distinguished as “whole” apart from the mainstream.

It is through the creation of the term Affrilachian that African American Appalachians are distinguished and “turned into subjects of their history and experience” (178). Naming plays an important role to Affrilachian identity because it works rhetorically to build a solid, identifiable name for outsiders-on-the-inside - allowing them to work beyond the flux of negotiation and towards the confidence that comes with self-identification and a larger cultural acceptance of that identification. Bhabha claims that narratives from the periphery are extremely important because they disrupt the false sense of collectivism established in traditional retellings of a group’s history. He calls such retellings “pedagogical” because they “teach” the group’s peoples to imagine themselves as homogeneous (147-8). To interrupt this pedagogical homogeneity, we perform our identities in the present-tense - changing historical conceptions.

This kind of performance didn’t take hold for African Americans of Appalachia until 1991, when Frank X Walker observed that Webster’s dictionary still defined an Appalachian as a “white resident from the mountains” (Affrilachian, “History”).7 It was this disturbing observation that inspired him to create the term Affrilachian and draw attention to the group’s widespread invisibility. He explains the urgency and function of the term in Coal Black Voices, the first video documentary on Affrilachian art:

One of the things I’ve encountered traveling outside Kentucky is having to defend the fact that people of color actually live here…. I’m trying to say that not only are we here, we’re here in a very large way. We’re part of Kentucky’s history. We’re part of the landscape. And, you know, we’re part of the lore of Kentucky that includes basketball and horses and bourbon - that all those things that are Kentucky are also us. And I don’t feel the need to separate them. I’m trying to find ways to build those connections, to let people know. It’s part of my responsibility as an artist - as a Kentucky artist - to say that out loud. To defend my place here and my writing’s place here and my family’s place here and our community and how it fits into the entire notion of what Kentucky is.

Walker emphasizes connection, community, and collectivism. For him, the goal of Affrilachian poetry is to reveal, perhaps for the first time, the validity and importance of black experiences in the region. By repeating the plural pronoun “we” in the phrases “we’re here” and “we’re part of,” Walker defines himself as a member of a group that is undeniably present and connected to the region - which is not based solely in geography, but also in emotion and memory. Whether or not they look like traditional “Appalachians” - and whether or not they dwell within the geographic boundaries of the region - Walker, his family, and his poetry have a “place here” - a phrase he repeats three times in one sentence. In his repetition of “my place here,” he emphasizes a deep connection to the region, to the place where he comes from, to the place that others are surprised he comes from. It is his responsibility as an artist to show his presence - a responsibility that invokes action (or becomes rhetorical) via his poetry, especially as others read it and as he performs it:

Affrilachia 8

thoroughbred racing

and hee haw

are burdensome images

for kentucky sons

venturing beyond the mason-dixon

anywhere in Appalachia

is about as far

as you could get

from our house

in the projects

yet

a mutual appreciation

for fresh greens

and cornbread

an almost heroic notion

of family

and porches

makes us kinfolk

somehow

but having never ridden

bareback

or sidesaddle

and being inexperienced

at cutting

hanging

or chewing tobacco

yet still feeling

complete and proud to say

that some of the bluegrass

is black

enough to know

that being ‘colored’ and all

is generally lost

somewhere between

the dukes of hazard

and the beverly hillbillies

but

if you think

makin’ ‘shine from corn

is as hard as Kentucky coal

imagine being

an Affrilachian

poet

Viewed rhetorically, “Affrilachia” disrupts traditional understandings of Appalachian identity through its content and form. Take, for instance, the last few lines of the poem. Walker gives an entire line to the word but, a coordinating conjunction that marks contradiction or contrast. His move distinguishes the concepts presented before the conjunction from the concepts presented after it. Before but, Walker notes traditional understandings of Appalachians as whites: “Being ‘colored’ and all/is generally lost/somewhere between/the dukes of hazard/and the Beverly hillbillies.” The voices and experiences of black Appalachians are silenced in traditional representations of the region. Walker interrupts this silence: “but/if you think makin’ ‘shine from corn/is as hard as Kentucky coal/imagine being/an Affrilachian/poet.” Placing but onto its own line further distinguishes traditional understandings of Appalachia from new, revolutionary ones. His message is a difficult one to preach: it is “as hard as Kentucky coal” to disrupt tradition. By linking the difficulty of writing Affrilachian poetry with more typical images of struggle in Kentucky (i.e. moonshine-making and coal-mining), Walker disrupts the traditional silence of the African American experience so that he can be comfortable “feeling/complete and proud to say/that some of the bluegrass/is black.” His line breaks are particularly revealing here. Just as he used line breaks to emphasize the conjunction but, he uses them to emphasize wholeness. Only by acknowledging that “some of the bluegrass/is black,” and by taking pride in this claim, will Affrilachians feel “complete.”

According to C. Daniel Dawson, NYU professor of African Diaspora and Culture, Affrilachian poets aim “to find out who they are, to validate their backgrounds, to validate their pasts, to validate their roots” (Coal Black Voices). Walker’s method for performing validation is to simultaneously reject outsiders’ views of the region (e.g. Beverly Hillbillies) and affirm insiders’ experiences by drawing connections between them. In “Affrilachia,” these connections stem from food (“fresh greens and cornbread”), family values (“an almost heroic notion of family”), and work ethic (whether making shine or writing poetry, life is as “hard as Kentucky coal”). It is sharing - or a sense of “mutual appreciation” - that “makes us kinfolk/somehow.” By setting the word somehow - an adverb meaning “in some unspecified way” - on its own line, Walker acknowledges how strange it might seem for African Americans to claim a role in Appalachian identity. There’s little stress here on why or how this bond is created - only a sense of rhetorical urgency that the bond be recognized and valued.

We see a similar theme in his poem, “Kentucke," which ends: “We are the amen/in church hill downs/the mint/in the julep/we put the heat/in the hotbrown/and/gave it color/indeed/some of the bluegrass/is black” (Affrilachia 97). As he does in his artist’s statement of purpose, Walker repeats the plural pronoun “we” to designate the collective, inclusive nature of Affrilachian identity. In this stanza, we is connected with active verbs: “We are,” “we put,” and “we gave.” He uses the past-tense verbs put and gave to remind his readers that Appalachia’s history included and depended upon the experiences of African Americans. Their importance to Appalachian history validates their current status in the region. As a result, Walker can claim “I too am of these hills” and “indeed/some of the bluegrass/is black.”

To build these connections is to reshape conceptions of an Appalachian past and strongly influence Appalachia’s future. Walker’s poetry is both performative and pedagogical in this sense; he performs black identity by retelling (or “teaching”) its place in Appalachia, past and present. On the surface, it appears as though he conceives of identity in much the same way as postcolonial theorist Benedict Anderson, who imagines it as a “solid community moving steadily down (or up) history” (26). Although an individual will never meet all of his or her fellow community members, s/he “has complete confidence in their steady, anonymous, simultaneous activity” (26). By naming Appalachians white, Webster’s dictionary (and the long history that preceded it) limited understandings of the region’s people to one, collective race.

One could argue that by naming Affrilachians, Walker simply replaces one homogeneity with another. The collective “we” that excluded Affrilachians is merely reestablished as a collective “we” that includes them. Catherine Squires, for instance, has complained that we are often too quick to label groups (especially minority groups) as collectives, and forget to recognize the vast differences within these “counterpublics.” Instead, she urges us to keep at the forefront local discourses and individual, identity-building activities:

By trying to understand and describe what kinds of activities, discursive and otherwise, are generated by different Black publics and whether these activities nurture or hinder particular Black communities, it is possible to recognize the internal diversity of the larger Black collective. (453)

Yet I believe it is too simple to say that Walker’s neologism is simply a new act of pedagogical dominance because he didn’t just coin the term, request a change of definition, and then walk away. Today, scholars cite Walker’s epiphany that “there are no blacks in Appalachia” to reveal all kinds of hidden identities in the region.9 He didn’t merely inspire a new definition of Appalachian identity, in other words, but rather a new means of arriving at, or identifying identity within Appalachia. This new space for self and regional identity-recognition is not always collective (there is space for individual voices to challenge, conflict, confirm and negotiate) and not always static (as in a dictionary definition). It is interactive, networked, and viral - present-tense in the most performative sense possible.

It is here that (for our purposes) Bhabha’s differentiation between the pedagogical and the performative runs out of steam. Walker’s naming works in between both spaces, serving to revise history in a pedagogical way, and at the same time encourage individual, identity-building performances. What I argue here is that it makes much more sense for us to consider Walker’s naming and the resulting upheaval of static identity in Appalachia as a performative rhetorical ecology - a term that melds Bhabha’s emphasis on performance with Jenny Edbauer Rice’s idea of viral rhetorical ecologies. I borrow this latter term from Edbauer Rice’s 2006 RSQ article, “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies,” where she explains that language is constantly shaped into a multiplicity of pathways that resemble an active, ecological system: “The rhetorical situation,” she claims, “should become a verb rather than a fixed noun” (13). In other words, rhetoric is active and takes place within a space of “movements and processes” (11) rather than within material- and time-constructed borders.10 For Edbauer Rice, rhetoric is not a single voice, but a “concatenation” of voices that occur in an “ongoing space of encounter” (5-6). These voices become rhetorical when they e/merge, circulate, and influence more performances - catalyzing ecologies of rhetorical performances that transgress, establish, negotiate and redefine Appalachian identity. Walker’s neologism didn’t just influence more scholarship on minorities in Appalachia. It carved a space for African Americans to write, sing, circulate, and own their Appalachian identities - whether they live within or beyond the region. Before the term Affrilachia was used as the title of Walker’s first book of poetry in 2000, it appeared in ACE, a Lexington, KY-based mainstream magazine as early as 1992.11 Today, there are a growing number of Affrilachian poets, artists, and musicians that create a vibrant, performative ecology that emerged from Walker’s naming.

The new genre of Affrilachian poetry, for example, emerged as a direct effect of Walker’s early efforts. In 1991, he worked with writer-friends to establish the Affrilachian Poets (AP), whose website history section tells the story of their founding in this way:

The University of Kentucky’s Martin Luther King Jr. Cultural Center became its spiritual home, and Walker’s role as program coordinator made it a popular hang out for the student body which included the poets. In the center’s back room that was part library, part study space, part escape from the outside world, the poets shared new creations. A nearby elevator was also utilized, with the writers gathering in the cramped space, turning off the power, and sharing their latest works. Soon, Walker brought the idea of the name the Affrilachian Poets to the group who adopted the moniker with pride. Finney, then a new English faculty hire at UK, was welcomed to the fold, and the once nameless group of poets and friends had a new identity and a new sense of purpose. In addition to Walker and Finney, founding members included Kelly Norman Ellis, Crystal Wilkinson, Gerald Coleman, Ricardo Nazario-Colon, Mitchell L. H. Douglas, Daundra Scisney-Givens, and Thomas Aaron. They were soon joined by Paul Taylor, Bernard Clay, Shana Smith, and Miysan T. Crosswhite. (Douglas)

By naming themselves the Affrilachian Poets, the identifying term circulated as rhetorical agency. Poets, writers, teachers, and singers began creating work and naming it Affrilachian. “Brown Country” is a poem written by Affrilachian poet Nikkey Finney that shares her strange recognition that country music singers are almost all white: “I know black folks who scream in a holler and nobody ever writes a country song about them.” Her use of the verb screams to describe the act of singing is violent. It desperately asks: Why have these voices remained unheard? Finney works to reveal moments of confusing, limiting, and frustrating disconnect between cultural understandings of African Americans and Appalachians. When she sings country music in her car, she feels strangely situated between two identities.

Crystal Wilkinson, author of the acclaimed poetry collection, Blackberries, Blackberries, describes her status as an Affrilachian in a similar way.In Coal Black Voices, she reflects:

It felt like I was operating from the outside no matter where I was. I was black and operating on the outside…. With my writing, I always felt like that if I was going to be writing about my ruralness, then I had to approach that with a certain group. Or if I was going to be writing about my blackness, that was something different. And with the Affrilachian Poets, it validated my whole self and validated my own body of writing that…individually and collectively we had a message that could be understood and heard by the outside world.

By naming themselves Affrilachians, both Finney and Wilkinson created the rhetorical space they needed in order to be recognized as part of Appalachia. These rhetorical spaces galvanize revised conceptions of Appalachian identity through language - which becomes rhetorical as it influences other performative acts.

Download video: MP4 format | Ogg format

Blu Cantrell's "Hit 'Em Up Style."

Download video: MP4 format | Ogg format

Carolina Chocolate Drops perform "Hit 'Em Up Style."

I see a similar rhetorical identity-grappling in one of the most popular covers performed by the Carolina Chocolate Drops: “Hit ‘Em Up Style.” Borrowing from Blu Cantrell’s original R&B version of the song the Drops combine R&B beat-style with Appalachian string band instruments and vocals, and their performance of the song has received over half a million YouTube hits.

When African American old-time string bands like the Carolina Chocolate Drops and the Ebony Hillbillies travel beyond the mountains singing and playing Appalachian folk tunes, their performances become an active part of the rhetorical ecology of Appal/Affril/achia.12 The Ebony Hillbillies actually make it a point to perform in everyday, present-tense spaces like the NYC subway undergrounds and university unions.

The Carolina Chocolate Drops tour within and beyond the geographic boundaries of Appalachia, gaining international recognition and even recently winning the 2011 Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album. These direct (inter)actions with folks beyond the mountains are evidence of a viral rhetorical ecology that, through performance, constantly expands what it means to own Appalachian identity. Such performances are rhetorical because they utilize language, sound, and heritage to virally inspire other acts of identification.

Download video: MP4 format | Ogg format

The Ebony Hillbillies

Inspired by such rhetorical performances, I must ask: What would happen if we viewed Appalachia as a space of identity encounters - a space defined by interaction rather than geography or race? Seeing the space of Appalachia in this way would encourage us to revise our conceptions of the region’s people and extend the geographic boundaries that so often determine who is allowed to claim Appalachian identity. If we look for a moment beyond the conceptual benefits of this kind of revision and towards its more practical consequences, we’ll better understand the importance of the rhetorical performances I’ve shared here, especially for those who have migrated physically and conceptually beyond the geographic boundaries of Appalachia. Our ways of conceiving and defining Appalachian identity control the kinds of political, socioeconomic, educational, professional, and social support our governments and communities provide. In this way, naming and identification play no small part in supporting the region’s people.

Recall the moment in “Affrilachia” where Walker struggles with his sense of place: “Anywhere in Appalachia,” he says, “is about as far/as you could get/from our house/in the projects” (92). Between 1940 and 1970, more than seven million people left rural Appalachia to settle in urban cities (Obermiller and Maloney 133). Many Appalachian oral narratives reflect the inter-personal effects of such loss. The song, “Leaving Train,” for example, portrays migration as an expected part of life:

Mama’s coming home today,” sings the child-persona, “but she ain’t coming home to stay/There’s no work in our town. Everything’s near ‘bout closed down/The Company’s come and gone/and all the new folks moved on/Empty stores on empty streets/Empty bed where Mama sleeps… Someday soon I’m gonna ride/on the leaving train by Mama’s side/There’s a broken link in the family chain/and it’s all because of the leaving train. (Williams)

When faced with movement away from home spaces, a conflict of identity ensues, where conceptions of home must be renegotiated. Walker too, because of his sense of estrangement in Appalachian identity, feels a strong need to redefine his place in Appalachia in light of racial in/visibility and out-migration. Conflicts of identity are especially challenging for those who migrate beyond the geographic boundaries of Appalachia to urban landscapes in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan (Obermiller and Maloney 133).

In response to vast out-migration, the term “urban Appalachian” was created to identify and support Appalachian migrants who, because they were thought to be primarily white, have been called an “invisible minority.” In her 1995 study of illiteracy in the Greater Cincinnati region, for instance, Victoria Purcell-Gates identifies urban Appalachians as a “low-status, minority group of whom those in the mainstream are less conscious, and hence in some respects less sensitive to, than groups such as African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans” (187). She reasons that most attribute this lack of awareness “to the fact that Appalachians are overwhelmingly white and of European descent and thus blend into the white mainstream whenever the problems and issues of ethnic minorities, or ‘people of color,’ are raised” (Purcell-Gates 187).

Notice the lack of space for African American Appalachians in these definitions, which actually define urban Appalachians against blackness. In population studies conducted before 2005, researchers used race as the primary means of identifying urban Appalachians, who were assumed to be only white. Until the two most recent surveys were conducted in 2005 and 2010, census work in Cincinnati classified neighborhoods as Appalachian based on “poverty, percent of African American population, high school dropouts, joblessness rate, occupational status, and family size” (Maloney and Auffrey, Chapter 5). According to these methods, to be urban Appalachian is to be inherently not black - criteria that flat-out exclude African Americans.

This kind of identification and naming is of no little consequence when it comes to issues of socioeconomic assistance for urban African American Appalachians. When determining which cities it will provide with financial support and social programming, the ARC relies on geographic rather than performative definitions of identity. Theresa I. Myadze, professor of Social Work at Wright State University, published a study in 2006 that showed that urban blacks living within counties deemed Appalachian are more likely to receive ARC assistance and other resources. As a result, she found that “urban blacks in the selected Appalachian areas are faring better than their counterparts in selected areas of non-Appalachian Alabama in terms of a number of socioeconomic indicators” (52).

Using race as a means of identification, these censuses failed to acknowledge the identities of city-dwelling African Americans who migrated from Appalachia. When considering the historical influence of the “white hillbilly” stereotype we explored earlier, this failure to recognize urban Affrilachians is not necessarily surprising. It is, however, extremely limiting. Despite the fact that urban Affrilachians make up a small minority of urban Appalachians in Cincinnati, excluding them from population measurement erases an otherwise important cultural presence.13

It is here that performative rhetorical ecologies can positively influence the kinds of material support we provide for Appalachians both within and beyond the ARC’s borders. In 2005 - about a decade after Walker introduced the term Affrilachian - researchers began broadening their collection methods by working with the Cincinnati-based Urban Appalachian Council (UAC), which promotes Appalachian cultural heritage as a positive and powerful force and encourages identification with that heritage as a means towards self empowerment and community building (“Cultural Programs”).The UAC also offers a definition of urban Appalachians that is based on family roots in the “counties making up the Appalachian region” (Bennett 28). Most recently, the Cincinnati researchers worked with the UAC to conduct a phone survey of 2,007 randomly selected adults in 22 counties in the Cincinnati area - four of which were federally identified as part of Appalachia - to assess the various ways of identifying Appalachian adults (Ludke, “Identifying”). They asked participants whether they were first or second generation Appalachians (based on county of origin/birth) and whether they considered themselves Appalachians. What they found was that naming Appalachian identity is incredibly challenging. Many who had family roots in Appalachia didn’t identify themselves as Appalachians, while others born beyond central Appalachia weren’t accounted for in the study at all. At the 2011 Appalachian Studies Association Conference, lead researcher Robert Ludke explained that their study was especially limiting to urban Affrilachians, who are more likely to migrate from southern (rather than central) Appalachian counties.They conclude their report by acknowledging that the term Appalachian “may consist of multiple identities, depending on the criteria used, and convergence to a single identity may be difficult, if it is possible at all” (41). While much more research needs to be conducted regarding this challenge, it is essential that researchers continue to move beyond identification through racial signifiers - and to acknowledge liminal identity spaces. I would like to offer performative rhetorical ecologies as one means of justifying self-identification and broadening our conceptions of Appalachian identity.

In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson explains that “the fiction of the census is that everyone is in it, and that everyone has one - and only one - extremely clear place. No fractions” (166). It is the nature of the census to identify individuals categorically, which is problematic for minorities within minorities (i.e. urban Affrilachians) who inhabit a kind of indeterminate space within/between minority cultures. Collective, “pedagogical” understandings of identity cause the experiences of minorities to be ignored or invisible. Although the classification of “urban Appalachians” and “Affrilachians” is fairly new, these identities have (especially prior to 2005) been understood primarily through pedagogical approaches, which ignore rhetorical identity performances. What I recommend here is that we work beyond narratives of “originary and initial subjectivities” toward ones that produce the articulation of cultural difference, where “space and time cross to produce complex figures of difference and identity, past and present, inside and outside, inclusion and exclusion” (Bhabha 1). Minorities understand their cultural identity through the performance of cultural norms and non-norms: “The social articulation of difference from the minority’s perspective is a complex, on-going negotiation that seeks to authorize cultural hybridities” (2). The minority’s “right” to exercise power from the periphery of national culture depends not on the persistence of tradition, but on “the power of tradition to be reinscribed” (2).

The liminal spaces occupied by African American Appalachians are “reinscribed” through rhetorical performances that influence entire ecological scenes of negotiation and naming. The experiences of blacks in Appalachia were not circulated until they were named, not meaningful until they were performed, and not rhetorical until those performances inspired new conceptions of Appalachian identity. In other words, Affriliachian art authorizes and propagates identity through language performances that, when viewed together, create a viral ecology of rhetorical influence. Kentucky poet laureate, Gurney Norman calls this a “powerful thing” that works to change literary consciousness. In Coal Black Voices, he says: “I think we’re only in the early stages of really appreciating what a powerful thing this is - the strength of historic awareness and community memory as a binding force in what other people might call postmodern America.” Similarly, Temple University professor of Africana philosophy, Paul C. Taylor points out that the rhetorical effects of Affrilachian poetry are inherently political:

The idea to call someone an Affrilachian instead of an Appalachian is the first sort of step into the realm of the Affrilachian poet. And it’s a political step. And that first step informs everything that happens after.

Today, the term Affrilachian can be found in the Encyclopedia of Appalachia and even the New Oxford American Dictionary - a phenomenon that challenges the race-based dictionary definition that first inspired Walker to create the term. Naming Affrilachia inspired an entire genre of music and poetry, and carved a space for black experience within and beyond the mountains. It opens a space for countering master narratives of identity and resisting a pedagogical narrative of exclusion. We must recognize, value, and validate rhetorical performances from the periphery not only in our historical retellings of Appalachia, but also in our understanding of the region’s diverse population and the division of resources to its people. Through performances - whether dictionary definitions, poetry readings, percentages in a census survey, or music echoing through subway tunnels - Affrilachian identity exists within a viral rhetorical ecology that shapes and propagates experiences that, for decades, were silenced.

Notes

Technical Note: This essay is best viewed using Chrome or Safari. The embedded videos will not work for Firefox users or for users who have not upgraded to Internet Explorer 9. However, all readers can download and view videos using the links provided.

1 See Gates; Hayden; Inscoe; Lewis; Perdue; Smith; Trotter; Turner.

2 The mythic nature of these boundaries play a role in the poetry of James Still’s From the Mountain Valley. We’ll discuss out-migration more thoroughly in the second half of this exploration.

3 View the 1974 CCC’s statement on Students’ Right to their Own Language at "NCTE.org

4 John Hardigan, Jr. has made us aware of how whiteness comes with its own socialized assumptions and beliefs, and that whites (especially Appalachian whites, who can’t be distinguished from Caucasians based on skin color) are racial subjects too: “Instead of limiting racialization to an association with forms of disadvantage or marked terms of difference, I suggest we need to use the term to encompass the way whites, too, are socialized into a set of assumptions and beliefs about race. This entails seeing whites and people of color in similar terms, as racial subjects, though usually very differently positioned within society” (65).

5 For African American women of the region, these minority statuses are triply-folded.See Bickley, Ancella and Lynda Ann Ewen. Memphis Tennessee Garrison: The Remarkable Story of a Black Appalachian Woman. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2001.

6 The first known writing on blacks in Appalachia was published in 1916 by Carter G. Woodson (now known as the “Father of Black History”) in the Journal of Negro History. Tracing Appalachian contributions to the anti-slavery movement in the pre-Civil War U.S., Woodson refers to white Appalachians as “the friends of freedom in Appalachian America” (148). He cites the 1855 founding of Berea College, the first interracial and coeducational college in the South, as a courageous early example of the white mountaineer’s sympathy for and support of African American education and freedom. Woodson traced examples like these to a bond he noticed between blacks and whites in his early twentieth century Appalachian experiences. He ends his article by celebrating it: “In Appalachian America the races still maintain a sort of social contact. White and black men work side by side, visit each other in their homes, and often attend the same church to listen with delight to the Word spoken by either a colored or white preacher” (150).

7 Today, this error has been corrected to read: “a native or resident of the Appalachian mountain area.”

8 From Affrilachia, pages 92-3.

9 The most recent citation regarded the invisibility of GLBTQ Appalachians during the panel, “Queer Space in a Queered Place: GLBT Identity in Southern Appalachia” at the 2011 Appalachian Studies Association conference - the second panel on this issue in ASA conference history. This list published by Spectrum Publishing offers a fairly comprehensive list of readings on racial and ethnic diversity in Appalachia. Note that nearly all of these articles were written post-1991. Also, Berea College held a well-attended symposium on identity and diversity in Appalachia.

10 Also see Gerard A. Hauser’s Vernacular Voices: The Rhetoric of Publics and Public Spheres, which extends Habermas’ ideal bourgeois public sphere into a multiplicity of public spheres, wherein the discourse of “social actors who are attempting to appropriate their own historicity” (55) makes a public emerge. Like Rice, Hauser sees discourse as essential to the emergence of publics, and believes that our discourses are always multifaceted, contradictory, active, and interactive - or what other theorists might call “networked” (Cushman; Foster; Galloway).

11 ACE Magazine is currently working on digitizing its archives. Over a phone conversation on 3/16/2011, they explained that Affrilachia appeared in the magazine in the late 1980s.The Encyclopedia of Appalachia cites the first mainstream use of the term in November 1993 in ACE (246). On the University of Kentucky’s online list of Special Collections, I found a similar date: Gurney Norman’s interview with Frank Walker in “Affrilachian: Bluegrass Black Arts Consortium,” ACE Magazine, 12 November 1993.

12 John Whitehead is currently producing a documentary film on this revival. See the documentary's website for information about the film.

13 The most recent census identified about fifty urban Affrilachians in the Greater Cincinnati region by asking participants whether or not they or their recent ancestors migrated from central Appalachia. The results of this census, however, are currently being revised because the researchers believe that their definition of Appalachian geography was too limiting. Most African American migrants, for instance, come from southern Appalachian states, not central ones (Ludke, “Socioeconomic”).

Works Cited

"Af·fri·la·chi·an" n." New Oxford American Dictionary. Edited by Angus Stevenson and Christine A. Lindberg. Oxford University Press, 2010. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Purdue University. 16 March 2011. Web.

AffrilachianPoets.com . 2006. 23 April 2009.Web.

Allison, Peter, dir.Although Our Fields Were Streets. VHS. Peter Allison Productions, 1991. Video

Alexander, J. Trent.“Defining the Diaspora: Appalachians in the Great Migration.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 37.2 (2006):219-47. Print.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities.1983. New York: Verso, 1991. Print.

Bellah, Robert N. Habits of the Heart:Individualism and Commitment in American Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985. Print.

Bennett, Kathleen P.“Doing School in an Urban Appalachian First Grade.” Empowerment through Multicultural Education. Ed. Christine E. Sleeter. Albany: Slate University, 1991. 27-48. Print.

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture.New York:Routledge, 1994. Print.

Billings, Dwight B, Edwina Pendarvis, and Mary Kay Thomas. Eds. “From the Editors.” Journal of Appalachian Studies10.1/2 (2004): 3-6. Print.

“Celebrating the History of Appalachia.” All Things Considered. NPR. 7 May 2006. Radio.

Coal Black Voices . Dir. Jean Donohue and Fred Johnson. VHS. Media Working Group, 2001. Video

“Cultural Programs.” Urban Appalachian Council. 2007. March 2009. Web.

Cushman, Ellen.“The Rhetorician as an Agent of Social Change.” College Composition and Communication . 47.1 (1996): 7-28. Print.

Douglas, Mitchell L.H.“The Affrilachian Poets: A History of the Word.” AffrilachianPoets.com. 2006. March 2009. Web.

Eller, Ronald D.“Finding Ourselves: Reclaiming the Appalachian Past.” Appalachia: Social Context Past and Present. 3rd ed. Eds. Bruce Ergood and Bruce E. Kuhre.Athens: Kendall/Hunt, 1991: 26-30. Print.

Ergood, Bruce.“Toward a Definition of Appalachia.” Appalachia:Social Context Past and Present. 3rd ed. Eds. Bruce Ergood and Bruce E. Kuhre. Athens: Kendall/Hunt, 1991: 39-48. Print.

Foster, H. Networked process : Dissolving Boundaries of Process and Post-Process. Parlor Press: West Lafayette, 2007. Print.

Galloway, A. R. and E. Thacker. The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. University of Minn. Press, 2007. Print.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. Colored People. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. Print.

Hartigan, John, Jr. “Whiteness and Appalachian Studies: What’s the Connection?” Journal of Appalachian Studies 10.1/2 (2004): 58-72. Print.

Hauser, Gerard A. Vernacular Voices: The Rhetoric of Publics and Public Spheres. University of S. Carolina Press: Columbia, 1999. Print.

Hayden, Wilburn, Jr. “ Appalachian Diversity: African-American, Hispanic/Latino, and Other Populations. Journal of Appalachian Studies 10.3 (2004): 293-306. Print.

Higgs, Robert J., Ambrose N. Manning, and Jim Wayne Miller, eds. Appalachia Inside Out:Volume II. 1995. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2001. Print.

Inscoe, John. Ed. Appalachians and Race:The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2001. Print.

Lewis, Ronald L. Black Coal Miners in America: Coal, Class, and Community Conflict, 1780 - 1980. Lexington, KY: UP of Kentucky, 1987. Print.

Ludke, Robert. “The Socioeconomic and Health Status of Black Appalachian Migrants in the Cincinnati Metropolitan Area.” Appalachian Studies Association Conference. Eastern Kentucky Univresity. Crabbe Library, Richmond, KY. 12 Mar. 2011. Conference Presentation. Print.

Ludke, Robert L., Phillip J. Obermiller, Eric W. Rademacher, and Shiloh K. Turner. “Identifying Appalachian Adults: An Empirical Study.” Appalachian Journal 38.1 (2010): 36-45. Print.

Maloney, Michael E. and Christopher Auffrey. “Chapter 5: Appalachian Cincinnati.” The Social Areas of Cincinnati: An Analysis of Social Needs. 2004. March 2009. Web.

Myadze, Theresa I. “The Status of African Americans and Other Blacks in Urban Areas of Appalachian and Non-Appalachian Alabama.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 12.2 (2006): 36-54. Print.

Obermiller, Phillip J. and Michael E. Maloney.“Living City, Feeling Country:The Current Status and Future Prospects of Urban Appalachians.” Appalachia: Social Context Past and Present. 3rd ed. Eds. Bruce Ergood and Bruce E. Kuhre. Athens: Kendall/Hunt, 1991: 133-8. Print.

Obermiller, Phillip J.and Steven R. Howe. “Urban Appalachian and Appalachian Migrant Research in Greater Cincinnati: A Status Report.”Urban Appalachian Council. 16 November 2006. March 2009. Web.

Perdue, Theda. Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540 - 1866. Knoxville: UT Press, 1979. Print.

Purcell-Gates, Victoria. Other People’s Words: The Cycle of Low Literacy. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1995. Print.

Reese, James Robert. “Ray Hicks and the Oral Rhetorical Traditions of Southern Appalachia.” Eds. Higgs, Robert J., Ambrose N. Manning, and Jim Wayne Miller. Appalachia Inside Out:Volume II. 1995. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2001: 493-504. Print.

Rice, Jenny Edbauer.“Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 35.4 (2005): 5-24. Print.

Russell, Jack. “Looking in the Mirror.” Appalachia:Social Context Past and Present. 3rd ed. Eds. Bruce Ergood and Bruce E. Kuhre. Athens: Kendall/Hunt, 1991: 115-122. Print.

Smith, Barbara Ellen. “De-Gradations of Whiteness: Appalachia and the Complexities of Race.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 10.1/2 (2004): 38-57. Print.

Sohn, Katherine Kelleher. Whistlin’ and Crowin’ Women of Appalachia: Literacy Practices since College. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2006. Print.

Squires, Catherine R. “Rethinking the Black Public Sphere: An Alternative Vocabulary for Multiple Public Spheres.” Communication Theory 12.4 (2002): 446-68. Print.

Still, James. From the Mountain Valley: New and Collected Poems. Ed. Ted Olson. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 2001. Print.

Trotter, Joe William, Jr. Coal, Class and Color:Blacks in Southern West Virginia, 1915 - 1932. Urbana: UI Press, 1990. Print.

Turner, William H. and Edward J. Cabbell. Eds. Blacks in Appalachia. Lexington, KY: UP of Kentucky, 1985. Print.

Villanueva, Victor. Foreword. Whistlin’ and Crowin’ Women of Appalachia: Literacy Practices since College. By Katherine Kelleher Sohn. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2006. xiii-xv. Print.

Walker, Frank X. Affrilachia. Lexington: Old Cove Press, 2000. Print.

The Journal of Affrilachian Arts & Culture. Print.

Williams, Robin and Linda. “Live.” RobinandLinda.com. March 2009. Web.

Woodson, C.G. “Freedom and Slavery in Appalachian America.” The Journal of Negro History 1.2 (1916): 132-50.