Ryan Cheek, Missouri University of Science & Technology

Avery C. Edenfield, Utah State University

(Published September 19, 2022)

Trans*[1] communities across the United States are under assault by radical extremist forces seeking to inflame partisanship by promoting hateful ideologies as wedge issues. This phenomenon is playing out in all manner of mediums—from radio stations, television studios, and the Internet to courtrooms, convention stages, and the halls of Congress. A recent example of this phenomenon is an iteration[2] of the annual Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), where former president Donald J. Trump made villains out of a community of people who “face frequent experiences of discrimination, violence, social and economic marginalization, and abuse across [their] lifespan” (Stotzer). According to the Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide (TvT Worldwide) project, in 2020, “350 trans and gender-diverse people were murdered” and “98 percent of those murdered globally were trans women or trans feminine people” (“TMM Update”). The Human Rights Campaign is sounding the alarm about the “epidemic of violence” against trans* bodies (Ronan). None of that data even begins to grapple with the outrageously high suicide rate among trans* youth; indeed, the Trevor Project, which conducts an annual mental health survey of LGBTQ youth, reports that in the U.S. “more than half of transgender and nonbinary youth [reported] having seriously considered suicide” (Trevor News). Yet, Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) at CPAC claimed trans* individuals are the threat, bemoaning their role in “cancelling” Mr. Potato Head (Milligan).

Scholars in rhetorical studies are well equipped to reveal the hateful ideologies embedded in modern political discourse by bringing narrative accounts of trans* experiences to bear on transphobic violence. However, researchers must take care to prevent their methodological practices from exposing trans* communities to more violence through the revocation of opacity. This article is for rhetorical studies researchers interested in theorizing ethical research designs in relation to trans* communities, especially online communities which play a vital role in such research. The insight we offer here may also be of use to social justice minded researchers from any discipline who interact with more vulnerable online communities as part of their research activity. To be clear, we believe this article is useful for those researchers who identify with, as well as those who do not identify with, the more vulnerable communities with whom they are studying. In this text, the concept of qubits provides a structured medium for thinking through (im)material and (non)corporeal constraints of rhetorical research ethics concerning vulnerable online communities. There is a queerness to qubits—a strangeness unbound by binarism, making qubits an apt metaphor for thinking through queer and trans* research.

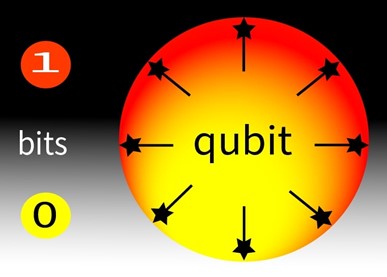

We have a lot to learn about vulnerability and ethics of care from the perspective of a qubit, which is precarious, shy, and mysterious by nature. A qubit is the quantum computing counterpart to a bit (Schumacher)—it too, upon measurement, registers as a zero or one. However, unlike a bit, a qubit that maintains quantum coherence contains all possibilities between zero and one (also including zero and one) due to its ability to superposition itself like a coin spinning, at once heads, tails, and neither heads nor tails, at least until it stops spinning. Refer to Figure 1 for an approximate visualization of the differences between bits and qubits.

Figure 1: Bits versus Qubits

By deploying metaphorical imagination as a disciplined, sense-making tool to theorize research ethics, we activate a methodology that, as rhetorical theorist Kenneth Burke (“Grammar”) puts it, “brings out the thisness of a that, or the thatness of a this” (p. 503). Readers in this article are invited to wonder about the simplistic complexity and abnormal normality of qubits that, we argue, may help us metaphorically reimagine a rhetorically invented approach to online research ethics. We call this approach qubit ethics.

In Ethics of Internet Research, Heidi McKee and James Porter advocate a rhetorical understanding of internet research ethics that, most importantly, complicates institutional frameworks for ethics which treat the internet as almost entirely public domain. Specifically, McKee and Porter argue that where text is ethically inert, interaction carries ethical entitlements afforded to human subjects. Their treatise is incredibly effective at highlighting the need for a more critical interrogation of online research projects than institutional review generally carries out. Where we depart from McKee and Porter is in the replication of binaries between text/interaction, public/private, and space/place. In the decade since their text was published, advances in technology have rendered many of these distinctions without much difference. Internet 3.0 is interactive, public, and everywhere. In positing a qubit ethics for internet researchers, we follow and then depart from McKee and Porter to engage in a more abstract and imaginative ethical construct equipped for a quantum world.

Qubits, or quantum bits, are more than a clever illustration of the complexity of research ethics, although they are that as well. Rather, we invoke qubits as a more-than-human provocation to think differently and deeply about the materiality and corporeality of our research designs. We acknowledge some may find our metaphorical choice unnecessary, confusing, or unnecessarily confusing—a state whose benefits are too often elided in the clarification of generative abstractions. Other metaphors may work better, but even in contemplating those, a reader is forced to reckon with the qualities of the rhetorical invention in front of them—and that, we believe, makes this an imperfectly playful text to teach, learn, and engage creative rhetorical theorizing about research ethics.

Qubit ethics are besides ethics and do not preclude ethical judgment, but this manuscript is not a manual; after all, “what sort of preparation for ethics is provided by reading the manual, and what sort of ethics is involved in writing one” (Mann, p. 200)? By re-posing Mann’s question, we do not mean to be dismissive of the just intentions ethics manuals often have, such as manuals instructing educators to use student-identified pronouns and adopt gender affirming classroom policies. Rather, we hope readers are challenged by our metaphorical blending of quantum computing and ethical reasoning to rethink traditional approaches to online research design in rhetorical studies.

Part of the origin of this article lies in an experience Dr. Avery Edenfield had in initiating an IRB protocol for a survey of trans* do-it-yourself (DIY) medical experiences in a public online forum and conducting research with trans people. IRB informed Edenfield that he did not need an IRB approval for online research on a public site (not behind a paywall and/or not requiring a login). For the survey, of course, IRB approval was needed and received (#8212). Academic analysis called scholarly and public attention to the publicly available information of trans* users, who were using a community for extra-institutional advice such as how to use crypto currency to order DIY cross-sex hormones through online vendors outside of the United States. In addition, Edenfield required a particular lens that allowed him to understand the unique precarity of this online community of trans* people.

Indeed, Edenfield was alerted to the ethically precarious nature of this situation due to public outcry online by some trans* users in response to a recently published article that reported on another similar online trans* community. This story relied on publicly available information and as such was not necessarily a violation of institutional research standards, yet the community expressed feeling exposed and violated after the article was published. They were not involved in the research design and did not talk to the author of the article herself. One might respond to this situation by thinking, “Well, it’s public. If you don’t want this information to be made more public, then use a private group or community.” However, private communities do not easily or quickly normalize trans* experiences, nor do they enable the pursuit of knowledge about trans* issues and medical knowledges—certain aspects of which are themselves not well known even in official medical discourses—let alone lower barriers to already liminal trans people who are seeking knowledge on the subject. In other words, one ethical motive for members of this community to make their knowledge public offers an issue that researchers have to address as a legitimate ethical concern that may or may not override their own self-interested purposes for studying more vulnerable populations. This research situation, we submit, is one of the major pressing concerns that will face any researcher who is interested in producing research about any marginalized population. While the ethical relations differ depending on whether one self-identifies with the community under question (e.g., queer, trans, gay, lesbian, African American) or is an outsider, there are always going to be ethical issues related to vulnerability.

In the following sections, we argue for adopting a qubit ethics, as a trans*material trans-corporeal ethics of care for compassionate and ethical research with more vulnerable online communities, as a way of accounting for both virtual and embodied risk these communities occupy. Notice the word “with” in the previous purpose statement; not research “on” but research “with” to emphasize the need for researchers to understand themselves in non-hierarchical relation to the community they seek to learn from (Itchuaqiyaq; Walton et al., “Values and Validity”). This work requires humility, generosity, and care at the deepest level we can muster. To that end, in the next section we begin a journey to the subatomic realm where we meet our protagonist, the qubit, or quantum bit, from whom we argue the research community may learn a lot. Then we trace social justice theorizing to ethics of care theorizing in rhetoric, writing, and feminist research practices. After setting up a foundation for inquiry, we turn to thinking through possibilities for how qubit ethics could alter our understanding of feminist ethics of care in both virtual and physical life. We end with a heuristic for applying a qubit ethics to digital research.

Vulnerability and an Ethics of Care

Social justice has become more established as an object of inquiry for scholars in the related fields of health, medical, technical, and public rhetorics. Despite this, as Agboka and Walton have noted, “a number of scholars—both emerging and established—have limited understanding of social justice” (para. 3) and reasonably wonder “‘How can I uphold principles of social justice in my research?’” (para. 3). From their observation, we discern an exigent need for theorizing and articulating generative ethical frameworks for enacting and practicing social justice in our research designs. One way we can do this work is by inventing rhetorical devices for reimagining research ethics that are creative enough to generate both criticism and reflection from present and future rhetorical studies research practitioners. Researchers have already examined some methods for social justice (Colton, Holmes, and Walwema; De Hertogh; Graham and Hopkins; Shields, 2008; Williams, “Black Codes” and “Survey”). Despite this work, queer populations have enjoyed less scholarly attention, with some notable exceptions (Alexander and Rhodes; Bessette; Cox; Edenfield et al; Gill-Peterson; Green; Moeggenberg and Walton; Narayan; Ramler; Scott). Anecdotally, our experience in presenting and publishing on queer rhetoric has been that there are a growing number of researchers who want to participate as allies. However, some allied researchers may lack methods for thinking through how researchers can ethically work with and alongside research populations that they may only relate to as outsiders.

Vulnerability

To encourage more ethical rhetorical studies research on trans* online communities, we examine the philosophical idea of “vulnerability” as a possible, but alone insufficient, ethical lens through which to theorize how researchers can come to view the ethics of their own research interests vis-à-vis trans* communities. Legal theorist Martha Fineman (“Vulnerable Subject”) argues that vulnerability “illustrates how human beings are dependent upon social institutions” and that social “institutions can address [structural harm] through law and policy that position vulnerability as the organizing principle” of building resiliency (268). Of course, others have pointed out some problems with Fineman’s juridical lexicon as justifying paternalistic lawmaking (Kohn), biopolitical securitization (Cole), and the reproduction of state capitalism (Davis and Aldieri). Although we agree with Fineman’s foundational critique of the western autonomous subject, we also agree with her critics that there is limited utility in subordinating an ontological claim to a juridical purpose. Rather, we follow Butler and Caveraro in grappling with vulnerability as part of a larger paradigmatic commitment to an “ethics of care.”

Ethics of care philosophy has been used by feminist ethicists in the 20th and 21st centuries (e.g., Held; Noddings; Tronto) to theorize how social and reciprocal relations of care function as a moral basis for identity and subjectivity. In Cavarero’s Horrorism: Naming contemporary violence and Butler’s “Rethinking vulnerability and resistance,” respectively, vulnerability moves beyond a commonsense understanding of the term as negative, or as vulnerable and in need of support from allies. Vulnerability is often figured as passivity, dependency, powerlessness, and deficiency. Non-majority populations are figured by an external lack, and vulnerability is figured as an imposed condition or constraint to be identified and critiqued. In a comment we do not mean as critical, we can find exactly this figuration deployed by De Hertogh: “Vulnerable communities, therefore, lack some of the institutional protections that extend to more traditional research settings” (9). While not losing sight of vulnerable communities and identities, Cavarero noted such figurations tend to lead to problematic responses to vulnerability, such as minimizing the forms of ethical responsivity to wide varieties of vulnerability that we sense. Instead, she argued that vulnerability is not an external obstacle to be remediated but is instead an ontological condition that describes the state of being human.

Building on this concept, we argue that the definition of vulnerability, like the meaning of the terms oppressed and under-resourced, has a significant impact on how we frame and respond to the needs of non-dominant gendered, raced, and ethnicized identities. As Cole points out, it is important to understand that “people are subjected to or immunized from vulnerability in radically distinct, different, and unequal ways” (p. 266). This is why trans* should not be understood as a monolithic identity category in research. Some trans* individuals will be more vulnerable than others. Caitlyn Jenner, for example, faces the violence of transphobia, but she does so from the vantage point of someone with access to great personal wealth, permissive medical care, and white privilege. Jenner was not subject to the same degrees of “wounding” in Cavarero’s sense as, for example, CeCe McDonald, a Black trans* woman who was wrongly imprisoned for defending herself against a transphobic and racist attack. It should not be controversial to observe that vulnerability, much like identity, exists on a complicated multi-dimensional spectrum of possible lived experiences, precisely the complexity that qubit ethics can help us imagine.

Vulnerability and Internet Research

Colton et al.’s article on tactical technical communication of hacktivists is a good example of ethics of care-related in-situ vulnerability in the context of online research. Beyond Colton et al., the ethics of care aligns with the rhetoric of research-related vulnerability itself. In the context of feminist ethics of care, De Hertogh directly appeals to rhetoricians who study health and medicine to theorize and study vulnerable populations. To be clear, parts of De Hertogh’s analysis, which includes a summary of some existing guidelines for ethical online research such as the Association of Internet Research (AoIR), highlight the need for a flexible framework. For example, she quotes the AoIR’s six general principles for online research:

(a) understand the need to protect vulnerable communities, (b) use practical judgments to avoid causing harm, (c) recognize that digital data represents people, (d) balance the rights of subjects with the social benefits of research, (e) embrace the evolving nature of online research, and (f) engage in deliberative decision-making that reflects a broad range of information and recommendations. (Markham and Buchanan 4)

By including these guidelines, De Hertogh evidences her concern, in part, with the ways in which vulnerability is defined by institutions (and not just the AoIR), individuals, and organizational values in ways that do not map onto the actual experiences of those they seek to study. Highlighting the need to pay attention to how vulnerability is defined, a previous study by Gustafson and Brunger went so far as to suggest that some communities identified as vulnerable by IRBs do not see themselves as at-risk and, in turn, may balk at the use of the term “vulnerable” as patronizing or misrepresentative. De Hertogh noted, “Ultimately, what the commission as well as Gustafson and Brunger revealed is that vulnerability is fluid and must be understood in situ” (9). With our own research project on trans* online writing, online anonymity further complicates notions of a stable research subject. De Hertogh claimed that we “need new methodological approaches to help us contend with ethical decisions unique to online research” (10), and articulated one such ethical approach:

For rhetoricians of health and medicine, establishing these relationships is important because issues of health and illness often increase the vulnerability of the populations we work with and, therefore, our obligation to minimize potential harm . . . Therefore, we must be aware of how our digital presence and interactions with vulnerable online communities can both foster meaningful relationships and reinforce discursive hierarchies. (20)

This framing of vulnerability is productive. However, it still functions as a general appeal to think more broadly about how we consider the ethics of more vulnerable populations. In other words, there remains a question as to what “vulnerable” means. We contend that this remaining question may be because vulnerability as a construct within an ethics of care framework has struggled with white, able-bodied, cis human morphology—a methodological flaw that suffocates the transitivity of bodies and matter (Halberstam, “Gender Transitivity”). In Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Barad took note of this problem, writing that “the most crucial limitation of Butler’s theory of materiality is that it is limited to an account of the materialization of human bodies […] through the regulatory action of social forces” (209). To be fair to De Hertogh, her aim is primarily to call for flexible ethical frameworks as well as to highlight the differences between face-to-face and online research, not to reconsider research ethics. To supplement her aims, we engage Barad’s application of quantum field theory (QFT) to trans*materiality (Meeting and “Transmaterialities”) alongside Stacy Alaimo’s concept of trans-corporeality, which “does begin with the human—paradoxically perhaps—to disrupt Western human exceptionalism” (“Trans-corporeality” 435). The combination of these theories enables a more imaginative, complex, and posthuman understanding of vulnerability at a quantum level.

Some ethicists at this point may be skeptical about how a framing of ethics could arise from a perspective without presuppositions relying on human wholeness (e.g., dignity, equality, sentience, and value to life). After all, what is ethics sans limits? To which we’d quip back, what to a qubit is ethics? Limitations are binary and unsuitable for quantum imaginings. It may be more accurate to consider qubit ethics an anethics rather than an ethics proper. Stemming as it does from a rhetorical perspective, qubit ethics does not preclude judgement, but judgement is not the point of qubit ethics either. While grappling with articulating anethics, Paul Mann has written that “insofar as all ethical treatises appeal to a desire for consolation—to an appearance of law, the good, the security of a choice within bounds—anethics should be an ethics without consolation [...] a writing that becomes the conscious practice, the impure reflection, of its ethical impossibility. An imperative impossibility: anethics” (199). Qubit ethics are an ethics without consolation; they are an impure reflection of ethics unmoored by appeals to abstractions like goodness or moral character. Rather, qubit ethics, as anethics, reveal intra-activity as universal connection between all beings and all things. This does not mean that qubit ethics are about collapsing meaning and morality into relativistic philosophical pondering.

“Without consolation” is not a forgoing of compassion, support, empathy, and the like; to the qubit, these qualities are expressed without imperative because they are endemic to the entangled quantum field. Qubit ethics complicate rather than clarify expanding consciousness and consciences in the quantum era we are living through where the boundary between physical and virtual life, much like many other contemporary binaries, is more porous than ever. In the next section, we extend ontological vulnerability beyond the spacetimemattering (Barad, “Transmaterialities” 393) of human form and into the virtual void where we hope to articulate a qubit informed ethics of care for researchers studying with trans* online communities.

Metaphorical Imagination as Methodology

At a subatomic level, energy shifts and shuffles across a quantum field—only ever finding temporary shelter in one state before transitioning to another—electrons intra-acting with virtual particles in a vacuum. In “Transmaterialities,” Barad puts it this way: “Virtual particles are not in the void but of the void. They are on the razor’s edge of non/being,” which means “virtuality is the material wanderings/wonderings of nothingness; virtuality is the ongoing thought experiment the world performs with itself” (396). Thought experimentation is also the basis of theory building, or what organizational scholar Karl Weick articulated as the artificial selection of disciplined imagination. To engage theoretical rhetorical constructs that can often be impenetrably dense to unpack—like vulnerability, ethics of care, and online discourse communities—we engage in metaphorical imagination (Abdullah) as a rhetorical methodology of “wonder in the face of the as yet unknown but observable” (Hawhee 90). What may metaphor do for readers that more concrete explanations may be less effective at achieving? As Kenneth Burke wrote in describing the work of Longinus, “imagination persuades by going beyond mere argument” (“Rhetoric” 79); that is to argue that the suasive effectiveness of metaphorical imagination is driven more by sublimity than reason. Muhammad Tanweer Abdullah argues that “metaphor allows a deep-seated, however partial, contextual analysis of complex and challenging settings through creative thinking and reflexivity” (42).

In our imagination of qubits in this text, ethics is a metonym for physics. We have chosen qubits as our paradigmatic lens because we are drawn to them as a relatively new phenomenon characteristic of the late anthropocene epoch. Qubits are being put to work even without fully understanding them—a condition sometimes present in the relationship between rhetorical studies researchers and more vulnerable online communities. For example, quantum computing promises gains in everything from artificial intelligence to financial services, but it also threatens to undermine the cryptographic encryption basis of the modern information superhighway. It isn’t yet clear whether the best solution to that problem—scaling up qubit powered networks to replace the modern internet—is even possible (Battersby; Kirsch). We could end up gaining qubit-powered processing at the expense of privacy, stability, and security in the quantum age.

Qubits, like other phenomena in quantum physics, are notable because of their seeming impossibility and curious yet useful misbehavior. They are also thingified more often than personified—a denial of the intra-active generative energy and potentiality of qubits. Lakoff and Johnson have argued that “metaphor is primarily a matter of thought and action and only derivatively a matter of language” (153). By this statement, they are delineating a comparison theory of metaphor, which relies on objective linguistic similarity, from more imaginative uses of metaphor that rely on experiential and possible similarity. The former limits metaphor to pre-established relationships, while the latter activates metaphor as a potential creator of relationships. Readers may be familiar with the syllogistic logic on standardized exams, which relies on comparison theory: apples are to oranges as onions are to carrots (fruits are to fruits as vegetables are to vegetables). In contrast, new metaphors invest agentic potential in the metaphor itself to forge creatively meaningful connections between linguistically dissimilar things: work was hellish, writing is gasping for thought, the physical is virtual, etc. Following a new metaphor approach, our use of qubits should not be read as tangential to our project or as an extraneous overindulgence in fraught linguistic comparisons. Rather, our use of qubits is intended to drive more ethical rhetorical studies reflection and research on more vulnerable online trans* communities.

Qubits, we argue, can help us imagine new ethical modes of relation and being (and non-relation and non-being) in rhetorical online research designs. Skepticism about the metaphor we have chosen is expected and welcome. We have chosen a complicated comparison on purpose to maximize the distance principle of metaphorical imagination. The distance principle suggests that “for a metaphor to be apt and effective, the conjoined target and source concepts need to come from distant domains in our semantic memory” (Cornelissen 1591). We take this to mean that the more disparate a linguistic relationship represented by a metaphor, the more effective the metaphor is at generating new understandings about both the target and source concepts the metaphor is built from. Lakoff and Johnson write, “In most cases, what is at issue is not the truth or falsity of a metaphor but the perceptions and inferences that follow from it and the actions that are sanctioned by it” (158). Quantum physics and research ethics are disparate phenomena that come from distant domains of our (and we hope our readers’) semantic memory. The qubit metaphor should not be judged by its truth or falsity, but rather by the entailments that follow from it.

Online communities are, we argue, expressions of material wanderings and wonderings through the void space of digital networks, where participants, like virtual particles, play out intra-action on an unending temporal-spatial field of possibility. Infinite potentiality, however, comes prepackaged with the infinite potential for disruption—which is why a researcher’s presence in an online community, like the introduction of free radicals to a homeostatic environment, risks parasitically absorbing the energy that constructs, animates, and powers online communities. There is a hybridity to online communities that marks them as both existing and not existing, perhaps best explained by the principle of quantum superposition which holds that if a system can exist in multiple arrangements of fields and particles, then it is most generally characterized as a combination of all possible arrangements (Dirac). In one sense, the existence of online communities is indisputable. We can find them, we can read them, we can interpret them, and we can participate in them. In another sense, online existence is ethereal—avatars and handles are apparitions whose subjective wholeness in digital contexts is dependent on imagination. Being online is also timeless in the sense that words and images are permanently encased as internet detritus to be encountered time and again.

To account for such quantum strangeness in our online research designs, in this text we articulate a sense of qubit ethics to argue for the inclusion of a trans*material trans-corporeal ethic of care in researching online trans* communities specifically, and all vulnerable online communities more broadly. Inspired both by our own prior research experiences and by De Hertogh’s application of feminist ethics of care to digital research, we draw on Barad’s trans*materiality and Alaimo’s concept of trans-corporeality to articulate a digital vulnerability that transgresses the physical constraints of flesh and metal. To be clear, this article should not be construed as “here is how you research online trans* communities” because such a prescriptive approach would harmfully and reductively posit trans* communities as a singularity that does not exist. Rather, our purpose in this text is to explore the challenges and possibilities a hybrid quantum/trans*/feminist theory of research in virtual environments poses for online research practices.

There is currently no quantum network that exists anywhere in the world near the scale of the Internet (although we may well have one soon—see Hurley), but there does not have to be to understand that the intra-activity between a person and their online self exists in the indeterminate soup of its own quantum field. When a lived physical identity is transformed into code to traverse the globally networked communication highway, an online life is born out of the intra-active mixture of physical (bodies, cables, input devices, scenes, processors, etc.) and virtual (profiles, images, platforms, chat boards, bots, etc.) realities. For example, online dating profiles are often preceded by physical identities articulating virtual selves whose encounters with others’ virtual selves may produce physical intra- and inter-activity. Extending Barad’s understanding of virtuality in quantum spaces as an ongoing thought experiment the world plays with itself, online selves are the thought experiments we play with ourselves. That is, what happens online impacts one’s physical reality—even if it is just biochemically driven emotional reactions to virtual inducements and enticements (for example, the gamification of Facebook). The virtuality of online identity is like the virtual particles Barad (“TransMaterialities”) finds so fascinating—both involve generative intra-action.

Qubits as a Heuristic for Research Ethics

Following Alaimo’s call for “thinking as the stuff of the world” (“Trans-corporeality” 435), we suggest thinking like a qubit when it comes to theorizing ethics for researching online communities. Table 3 articulates the four strange quantum properties of qubits that inspire and inform a qubit ethics approach to internet research with more vulnerable communities.

Table 1: Entailments of Qubit Ethics for Internet Researchers

|

Qubit Properties |

Definitions of Properties |

Entailments for Internet Researchers |

|

Superposition |

the ability to contain all possibilities at once (*) |

Texts are both interactive and inert. The same internet research can both harm and help others. |

|

Entanglement |

the ability to communicate faster than the speed of light without regard to spatial distance or physical connection |

To research online, one must be online. Virtual presence entails physically lived realities elsewhere. |

|

Tunneling |

the ability to pass through impassable physical barriers (teleportation) |

Spillage will occur. The effect of internet research cannot be contained to virtual life. |

|

Decoherence |

the inability to maintain form once measured (shyness) |

Observed communities may dissipate. Internet researcher presence is destabilizing. |

By theorizing vulnerability through the above qubit properties, we hope to better fuse ethics with mattering. In Meeting the Universe Halfway, Barad argues “Ethics is about mattering, […] including new configurations, new subjectivities, new possibilities […] we are already materially entangled across space and time with the diffractive apparatuses that iteratively rework the ‘objects’ that ‘we’ study” (384). We take Barad’s argument as a call to theorize a new ethics from new vantages; in particular to think about the relationships between existence/nonexistence, the physical/virtual, and being/nonbeing as a perspective for ethics. What we propose will be disputed as ethics as it operates from a position without limitation; that is, online communities are quantum communities in that they contain multitudinal potential spread across an electronic void. Cycles of energy converting into matter converting into energy connect us in deeper ways than Cavarero’s and Butler’s respective vulnerability constructs, which rely on a sense of wholeness, can explain—especially in the context of the intra-actions between virtual and physical life.

Intra-actions, or what Barad calls “self-touching,” enable self-experimentation and self-change. To put this another way, a person is both their online profile and not their online profile (Almjeld; Degen and Kleeberg-Niepage; Lemke and Weber). Both shared and distinguishing characteristics between the virtual and physical selves are contingent on intra-action, but it can cut either way. That is, you may present in-real-life (IRL) one way in the physical world that is confirming or disconfirming of how you may present online (or vice versa), but both identities are “you” existing in multiple spaces (and times) at once. Have you ever tripped while tweeting on your phone? If you have not, then another way for you to experience this phenomenon right now is by googling yourself. What did you find? Perhaps a work profile, a personal website, or if you use social media, probably some links to your profiles on all the major platforms (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, etc.). Digging deeper, like a good researcher, perhaps on page two of the search results, you find past you’s on a defunct Reddit message board or MySpace page, or maybe an embarrassing childhood photo or a mugshot from your hometown newspaper’s website. All of these are you and not you. Experiences drawn from a physical life that has and is being lived, yet virtually imitated by strategic groupings of electrons.

“Self-touching” may be sensed in Cavarero’s and Butler’s (“Rethinking”) constructs for vulnerability. In contrast to rational approaches and ideas of a self-present subject, vulnerability figures the self as constituted by its exposure to social and environmental forces. That is, the self is not self-present since who we are changes depending on the relations we are exposed to, the people we are with. The goal, as Butler wrote in Giving an Account of Oneself, is to “affirm what is contingent and incoherent in oneself” as a starting point for a new bodily ontology (41), or what Cavarero called an “altruistic ethics of relation” (92) whereby the self exists in reciprocal relations of vulnerability and exposure. What is more affirming of one’s incoherence and contingency than infinite self-touching? As Barad has observed in “TransMaterialities,”

Every level of touch, then, is itself touched by all possible others. Particle self-intra-actions entail particle transitions from one kind to another in a radical undoing of kinds — queer/ trans*formations. Hence self-touching is an encounter with the infinite alterity of the self. Matter is an enfolding, an involution, it cannot help touching itself, and in this self-touching it comes in contact with the infinite alterity that it is. Polymorphous perversity raised to an infinite power: talk about a queer/trans* intimacy! (396)

At a subatomic material level, we are connected through spacetimemattering and the queer/trans* impulses of particles that cannot help but touch—themselves and other particles; a connectedness built in part on a foundation of ontological vulnerability, but ultimately constituted by a sort of quantum jouissance, an intra-interplay of touching-derived pleasure always already occurring in and around us. Such atomistic intimacy also calls into question the utility of Cavarero’s articulation of dismemberment and horrorism.

Cavarero defines an ontological crime as a form of physical violence that does not allow an individual to maintain bodily integrity or, conversely, does not allow for a human body to be recognized, what she calls horrorism: “a body in which human singularity, concentrating itself at its most expressive point of its own flesh, exposes itself intensely” (15). Horrorism has no concern for others. Cavarero has argued that it “aim(s) to destroy the uniqueness of the body, tearing at its constitutive vulnerability. What is at stake is not the end of a human life, but the human condition itself” (8). It is important to note that vulnerability, like Barad’s agential realism (Meeting), is relational, which is precisely why Colton et al. introduced Cavarero’s thinking to technical communication audiences in the context of identifying which forms of tactical communication are ethical or unethical. We support their reading but wish to add that vulnerability for trans* audiences requires additional elaboration precisely because some trans* bodies, seemingly paradoxically, may undergo a form of self-wounding affirmation independent of cis-normative conceptions of a human singularity or bodily integrity.

For Cavarero, the experience of dismemberment is an “absolute harm”; however, for some trans* individuals, a breach of bodily integrity is a necessary step toward ontological affirmation. “Wounding” should not apply to trans* bodies undergoing transition, but instead to the act of wounding by transphobic ontologies. Constructions of ethics that posit human singularity as a starting point or goal risk aiding regulatory regimes built on normalizing bodies through violent erasure. Applying Cavarero’s thinking to more vulnerable trans* bodies, thus, requires some qualification since they are not “normative.” That is, it is very easy to understand ontological integrity when we are presupposing cisgender identities content with the bodies they were born to, but it is not the same end (clearly) as horrorism[3].

By contrast, trans* bodies, with Stryker’s discussion of Frankenstein’s monster as a representative anecdote for trans* beings, literally undergo a form of dismemberment, even as it is in the ethical service of affirming ontological integrity instead of removing a person’s singularity (see Edenfield et al.). In sum, thinking beyond corporeal boundaries is critical—self-touching particles are often engaged in biomimetic cutting here and there (Barad “TransMaterialities”). Quantum dismemberment is not “absolute harm”—in fact, it may be understood as a basis for creation and relation. Barad’s theory of agential realism and Alaimo’s ontology of trans-corporeality enable new thinking about trans* online communities, trans* bodies, and vulnerability.

Anti-trans activists often use gender affirmation surgery to muster public outrage to their cause, posting grotesque and shocking images, using transphobic language, and twisting concepts of vulnerability to keep people from "mutilating" themselves (Salamon; Stone). As quantum beings, humans are always already transitioning in an infinite virtualization of all possible combinations of ourselves—although the degree to which we may do so differs based on relative privilege. For many, these productive dismemberments occur first online, where virtualized experimentation is possible and even structurally encouraged in anonymous message boards and second-life type simulations (for example, augmented reality apps that display possible outcomes of facial feminization surgery). Qubits point to the need to understand vulnerability trans*materially and trans-corporeally as a consideration for the precarity of virtual life in its intra-active engagements with physical life.

Helping to dissolve bounded constructions of a bodily integrity, trans-corporeality “suggests a new figuration of the human after the Human, which is not founded on detachment, dualisms, hierarchies, or exceptionalism”; rather, trans-corporeality “insists on multiple horizontal crossings, transits, and transformations” (Alaimo, “Trans-corporeality” 436). Under such a paradigm, the boundaries between flesh and environment dissolve as corporeal form gives way to the ethereal ecologies that shape it. For example, Neimanis and Walker’s application of trans-corporeality to climate change effectively demonstrated the inseparability of human bodies from weather—an entanglement that offers a paradigmatic shift away from mere relatedness to climate and towards an understanding that we are worlding with weather. Similarly, trans-corporeality has been used to break binaries between bodies, times, and spaces in a variety of contexts such as landscapes in biomolecular archaeology (Fredengren), the toxicity of 9/11 (Zarranz), naked protests (Alaimo “The Naked Word”), and regendering in Afro-Diasporic Vodou (Strongman). What these examples have in common is that they each use a trans-corporeal framing to break false boundaries between humanity and more-than-human others. One key contribution this text makes is to leverage trans-corporeal theorizing to traverse the borders between life and virtual life that may enable problematic research practices when it comes to more vulnerable online communities. This article demonstrates the clear need to push trans-corporeal theorizing to the sub-atomic virtuality of quantum fields, where the intra-actions of our bodies, our identities, and our things play out.

Superposition is the ability to contain all possibilities at once (*). The intra-activity of virtual and physical selves mimics the superposition qualities of the qubit. That is, the identities of qubits and quantum beings are perpetually in flux, yet also paradoxically stable. Superpositioning offers researchers a path beyond the type of binary thinking that sustains transphobia and other hateful ideologies, yet superposition does so without succumbing to an equally pernicious postmodern evacuation of meaning and materialism. The primary presupposition of qubit ethics that keeps it from collapsing into relativistic nihilism is that all beings—virtual and physical—share a deep connection at a quantum level unexplainable by traditional physics or ethics. Binaristic ethics wound, while ethics absent any boundary or grounding erase—neither posit a solid foundation for researching with more vulnerable trans* online communities.

Entanglement is the ability to communicate faster than the speed of light without regard to spatial distance or physical connection. Research designs that involve more vulnerable online trans* communities should consider that virtual and physical life are always already entangled at the subatomic level. What researchers do in either virtual or physical space or time will impact research subjects in their own virtual or physical space or time. Entanglement reminds researchers that caring for others is also caring for the self; that is, no amount of professional distance from the more vulnerable communities that researchers engage with can overcome the potential for interactive harm entirely, so tread cautiously.

Tunneling is the ability to pass through impassable physical barriers (teleportation). Tunneling teaches us that there is no real or virtual boundary for the occurrence of intra-interaction between researchers and the communities with whom they research. Researchers must recognize that the perpetual spillage of quantum particles between the virtual and physical planes means unpredictable harm can occur to all participants in a research project no matter what precautionary barriers are constructed. Such a point is often included in the informed consent documents research subjects sign, but is not usually fully internalized by researchers and researched communities alike.

Decoherence is the inability to maintain form once measured (shyness). Finally, as we suggested above, decoherence offers an alternative to thinking about concepts like vulnerability, dismemberment and horrorism. To be clear, in using the term decoherence, we are metaphorically playing on quantum rhetoric rather than the psychoanalytic or psychotherapeutic entailments of coherence as it relates to self-perception and identity—although we also acknowledge the comparison may be fruitful. Like qubits, online communities can be paradoxically fragile and resilient. Researchers should take extra care when disturbing or even observing them as they risk unjustly ending their perpetual becoming.

We are all subjected to the harms of the world, but not all of us are subjected in the same way, particularly in how the world forces us to negotiate our singularity in this exposure. Some bodies must be wounded to realize an ethical life, but this “wounding” differs from a common sense understanding of the word. We should leave behind concepts like ontological integrity in favor of more life affirming concepts like quantum jouissance—acknowledging the pleasure and pain bodies undergo in their connected separateness and occasional need for ontologically affirming reconfigurations.

Conclusion

As social justice praxis is recognized as an object of inquiry for researchers, it is important to observe that perhaps outside of social justice minded scholars, the shared agreement upon the meaning of groups worthy of the labels “oppressed” and “under-resourced” evaporates. The fields of public, medicine, heath, and technical rhetorics with their emphasis on application and practice are areas where queer theory can be put to work. This article examines the idea of “vulnerability” as an ethical framework for research that we have argued may be understood from the perspective of a qubit. Such metaphorical imagination is generative thinking about and besides ethics, but exists without consolation or boundary. By putting Caverero and Butler into conversation with Alaimo and Barad, we have argued here for a trans*material trans-corporeal ethics of care for researchers to consider when designing studies that involve more vulnerable online communities. This work has several implications for researchers. In line with De Hertogh, we must recognize that an IRB approval is just the beginning. As made plain by the anecdote that started this paper, in some cases, the IRB process may even clarify our need for additional ethical frameworks that go beyond regulatory systems in protecting more vulnerable communities from harm.

Additionally, research must begin to pay attention to trans* populations and their grave needs, especially considering recent moves toward greater disenfranchisement, and even more gravely, existential violence and erasure. However, importantly, we also recognize the benefit of applying ontological conceptualizations of vulnerability to other rhetorics of health and medicine involving marginalized populations, such as women of color who experience significantly higher mortality rates during pregnancy compared to white women (Rabin). We also believe expanded ideas about vulnerability as quantumly read can inform discussions on social justice outside the academy, challenging presuppositions about healthcare and what motivates policy and practice. For instance, one presupposition that is uniquely challenged by ethics of care, ontological vulnerability, and trans-corporeality is conventional understandings of the Hippocratic Oath, that we are supposed to protect people from wounds, keeping in mind the gender care manual Mascara and Hope’s warning about neo-vaginas as “wounds,” that gender confirmation surgery may necessitate the removal or re-composition of otherwise healthy tissue. In another example, “top surgery” necessitates the removal of breasts in transmasculine men to create a masculine chest. Yet, top surgery has been noted as having a significant impact on the quality of life for transmasculine individuals (Poudrier et al.). If Cavarero is right, then horror’s etymological relationship to dismemberment sets up presuppositions in rhetoric and research that oppress trans* communities. We need to challenge ideas and research that, knowingly or not, contribute to the wounding and erasure of trans* individuals and the communities, physical or virtual, they find shelter in.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jared S. Colton and Steve Holmes for their contribution to the development of this manuscript.

[1] We have chosen to use Trans* in this article because, as Halberstam has argued, “Trans* borrows from internet search protocols where an asterisk functions as a wildcard” (“Gender Transitivity” 368) and names “expansive forms of difference, haptic relations to knowing, [and] uncertain modes of being” (“Quick and Quirky” 5).

[2] We are referencing the “America Uncancelled”-themed CPAC conference held February 2021 in Orlando, Florida. Conference speakers focused on cis white cultural grievance in response to the perceived threat of “cancel culture” in American society.

[3] Thank you to Jared Colton and Steve Holmes for their help thinking through Caverero and Butler’s considerations of vulnerability and the body.

Abdullah, Muhammad Tanweer. “Metaphorical Imagination as Creative Evidence: Some Preliminary Thoughts.” Journal of Law and Society, vol. 32, no. 45, 2005, pp. 39–47.

Agboka, Godwin Y., and Rebecca W. Walton. “CFP: Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work: Theories, Methods, and Topics,” ATTW-L, 4 Sept. 2018, attw.org/pipermail/attw-l_attw.org/2018-September/000136.html.

Alaimo, Stacy. “The Naked Word: The Trans-Corporeal Ethics of the Protesting Body.” Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory, vol. 20, no. 1, 2010, pp. 15–36, doi:10.1080/07407701003589253.

---. “Trans-corporeality.” The Posthuman Glossary, edited by Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova, Bloomsbury, 2018, pp. 435–437.

Alexander, Jonathan, and Jacqueline Rhodes. “Queer Rhetoric and the Pleasures of the Archive.” enculturation: a journal of rhetoric, writing and culture, 2012, enculturation.net/queer-rhetoric-and-the-pleasures-of-the-archive.

Almjeld, Jen. “A Rhetorician’s Guide to Love: Online Dating Profiles as Remediated Commonplace Books.” Computers and Composition, vol. 32, 2014, pp. 71–83, doi: 10.1016/j.compcom.2014.04.004.

Barad, Karen Michelle. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke UP, 2007.

---. “TransMaterialities: Trans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Political Imaginings.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 21, no. 2-3, 2015, pp. 387–422, doi:10.1215/10642684-2843239.

Battersby, Stephen. “The Dawn of the Quantum Internet.” New Scientist, vol. 250, no. 3336, 29 May 2021, pp. 36–40.

Bessette, Jean. “Queer Rhetoric in Situ.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 35, no. 2, 2016, pp. 148–164, doi: 10.1080/07350198.2016.1142851.

Burke, Kenneth. A Grammar of Motives. U of California P, 1969.

---. A Rhetoric of Motives. U of California P, 1969.

Butler, Judith. Giving an Account of Oneself. Fordham Univ Press, 2005.

---. “Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance.” Vulnerability in Resistance, edited by Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Letticia Sabsay, Duke UP, 2016, pp. 12–27.

Cavarero, Adriana. Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence. Translated by William McCuaig, Columbia UP, 2009.

Cole, Alyson. “All of Us Are Vulnerable, But Some Are More Vulnerable than Others: The Political Ambiguity of Vulnerability Studies, an Ambivalent Critique.” Critical Horizons, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 260–277, doi: 10.1080/14409917.2016.1153896.

Colton, Jared S., Steve Holmes, and Josephine Walwema. “From NoobGuides to #OpKKK: Ethics of Anonymous’ Tactical Technical Communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 1, 2016, pp. 59–75., doi:10.1080/10572252.2016.1257743.

Cornelissen, Joep P. “Making Sense of Theory Construction: Metaphor and Disciplined Imagination.” Organization Studies, vol. 27, no. 11, 2006, pp. 1579–1597.

Cox, Matthew B. “Working Closets: Mapping Queer Professional Discourses and Why Professional Communication Studies Need Queer Rhetorics.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 33, no. 1, 2018, pp. 1–25., doi:10.1177/1050651918798691.

Davis, Benjamin P., and Eric Aldieri. “Precarity and Resistance: A Critique of Martha Fineman’s Vulnerability Theory.” Hypatia, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 321–337, doi: 10.1017/hyp.2021.25.

De Hertogh, Lori Beth. “Feminist Digital Research Methodology for Rhetoricians of Health and Medicine.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 32, no. 4, 2018, pp. 480–503., doi:10.1177/1050651918780188.

Degen, Johanna and Andrea Kleeberg-Niepage. “The More We Tinder: Subjects, Selves and Society.” Human Arenas, vol. 5, no. 1, 2022, pp. 179–195, doi: 10.1007/s42087-020-00132-8.

Dirac, Paul. A. M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th ed. Clarendon, 1958.

Edenfield, Avery C., et al. “Queering Tactical Technical Communication: DIY HRT.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 3, 2019, pp. 177–191, doi:10.1080/10572252.2019.1607906.

---, et al. “Always Already Geopolitical: Trans Health Care and Global Tactical Technical Communication.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 49, no. 4, 2019, pp. 433–457., doi:10.1177/0047281619871211.

Fineman, Martha A. “The Vulnerable Subject and the Responsive State.” Emory Law Journal, vol. 60, no. 2, 2010, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1694740.

Fredengren, Christina. “Posthumanism, The Transcorporeal and Biomolecular Archaeology.” Current Swedish Archaeology, vol. 21, no. 1, 2013, pp. 53–71.

Gill-Peterson, Julian. “The Technical Capacities of the Body: Assembling Race, Technology, and Transgender.” Transgender Studies Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 3, 2014, doi: 10.1215/23289252-2685660.

Graham, S. Scott and Hannah R. Hopkins. “AI for Social Justice: New Methodological Horizons in Technical Communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 1, 2022, doi: 10.1080/10572252.2021.1955151.

Green, McKinley. “Resistance as Participation: Queer Theory’s Applications for HIV Health Technology Design.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 4, 2020, pp. 331–344, doi:10.1080/10572252.2020.1831615.

Gustafson, Diana L., and Fern Brunger. “Ethics, ‘Vulnerability,’ and Feminist Participatory Action Research With a Disability Community.” Qualitative Health Research, vol. 24, no. 7, 2014, pp. 997–1005, doi:10.1177/1049732314538122.

Halberstam, Jack. Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability, U of California P, 2018.

---. “Trans* - Gender Transitivity and New Configurations of Body, History, Memory and Kinship.” Parallax, vol. 22, no. 3, 2016, pp. 366–375, doi:10.1080/13534645.2016.1201925.

Hawhee, Debra. Rhetoric in Tooth and Claw: Animals, Language, Sensation. U of Chicago P, 2017.

Held, Virginia. The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political, and Global. Oxford UP, 2006.

Hurley, Dan. “The Quantum Internet Will Blow Your Mind. Here’s What It Will Look Like.” Discover Magazine, 3 Oct. 2020, www.discovermagazine.com/technology/the-quantum-internet-will-blow-your-mind-heres-what-it-will-look-like.

Itchuaqiyaq, Cana Uluak. “Iñupiat Iḷitqusiat: An Indigenist Ethics Approach for Working with Marginalized Knowledges in Technical Communication.” Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work: Theories, Methodologies, and Pedagogies, edited by Rebecca Walton and Godwin Y. Agboka, Utah State UP, 2021.

Kirsch, Zach. “Quantum Computing: The Risk to Existing Encryption Methods.” Computer Systems Security, www.cs.tufts.edu/comp/116/arcchive/fall2015/zkirsch.pdf.

Kohn, Nina A. “Vulnerability Theory and the Role of Government.” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism, vol. 26, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1–27.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. U of Chicago P, 1980.

Lemke, Richard, and Mathias Weber. “That Man Behind the Curtain: Investigating the Sexual Online Dating Behavior of Men Who Have Sex With Men but Hide Their Same-Sex Attraction in Offline Surroundings.” Journal of Homosexuality, vol. 64, no. 11, 2017, pp. 1561–1582, doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1249735.

Mann, Paul. Masocriticism, State U of New York P, 1999.

Markham, Annette, and Elizabeth Buchanan. “Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee (Version 2.0).” Association of Internet Researchers, 2012, aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf.

Mascara and Hope. 2013, bytenoise.co.uk/oh-for-fucks-sake/mascara-and-hope.pdf.

McKee, Heidi A., and James E. Porter. The Ethics of Internet Research: A Rhetorical, Case-based Process. Peter Lang, 2009.

Milligan, Susan. “Trump, Mr. Potato Head and CPAC: Republicans Show Loyalty to Trump.” U.S. News & World Report, 26 Feb. 2021, https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2021-02-26/trump-mr-potato-head-and-cpac-republicans-show-loyalty-to-trump.

Moeggenberg, Zarah C., and Rebecca Walton. “How queer theory can inform design thinking pedagogy.” Proceedings of the 37th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication, 2019.

Narayan, Madhu. “At Home with the Lesbian Herstory Archives.” enculturation: a journal of rhetoric, writing and culture, 2013, enculturation.net/lesbian-herstory-archives.

Neimanis, Astrida, and Rachel Loewen Walker. “Weathering: Climate Change and the ‘Thick Time’ of Transcorporeality.” Hypatia, vol. 29, no. 3, 2014, pp. 558–575, doi:10.1111/hypa.12064.

Noddings, Nel. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education. U of California P, 2003.

Poudrier, Grace, et al. “Assessing Quality of Life and Patient-Reported Satisfaction with Masculinizing Top Surgery.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, vol. 143, no. 1, 2019, pp. 272–79, doi:10.1097/prs.0000000000005113.

Rabin, Roni Caryn. “Huge Racial Disparities Found in Deaths Linked to Pregnancy.” The New York Times, 7 May 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/05/07/health/pregnancy-deaths-.html.

Ramler, Mari E. “Queer Usability.” Technical Communication Quarterly, 2020, pp. 1–14, doi:10.1080/10572252.2020.1831614.

Ronan, Wyatt. “8 Bills Across 7 States: Coordinated Anti-Transgender, Anti-LGBTQ Legislative Push Ramps Up In State Houses Across The Country.” Human Rights Campaign, 10 Feb. 2021, www.hrc.org/press-releases/8-bills-across-7-states-coordinated-anti-transgender-anti-lgbtq-legislative-push-ramps-up-in-state-houses-across-the-country.

Salamon, Gayle. Assuming a Body: Transgender and Rhetorics of Materiality. Columbia UP, 2010.

Schumacher, Benjamin. “Quantum coding.” Physical Review A, vol. 51, no. 4, 1995, pp. 2738–47, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.51.2738.

Scott, J. Blake. Risky Rhetoric: AIDS and the Cultural Practices of HIV Testing. Southern Illinois UP, 2003.

Shields, Tanya L. “Critical Connection: Method, Power, and Knowledge.” enculturation: a journal of rhetoric, writing, and culture, vol. 6, no. 1, 2008, enculturation.net/6.1/shields.

Stone, Sandy. “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies, vol. 10, no. 2, 1992, pp. 150–76, doi:10.1215/02705346-10-2_29-150.

Stotzer, Rebecca L. “Data Sources Hinder Our Understanding of Transgender Murders.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 107, no. 9, 2017, pp. 1362–63, doi:10.2105/ajph.2017.303973.

Strongman, Roberto. “Transcorporeality in Vodou.” Journal of Haitian Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, 2008, pp. 4–29, www.jstor.org/stable/41715186.

Stryker, Susan. “My Words to Victor Frankenstein. Above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage.” Kvinder, Køn & Forskning, no. 3-4, 2011, doi:10.7146/kkf.v0i3-4.28037.

“TMM Update: Trans Day of Remembrance 2020.” Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide, 20 Nov. 2020, transrespect.org/en/tmm-update-tdor-2020/.

Trevor News. “Landmark Study Finds 39 Percent of LGBTQ Youth and More than Half of Transgender and Non-Binary Youth Report Having Seriously Considered Suicide in the Past Twelve Months.” The Trevor Project, 5 Oct. 2021, https://www.thetrevorproject.org/blog/landmark-study-finds-39-percent-of-lgbtq-youth-and-more-than-half-of-transgender-and-non-binary-youth-report-hav....

Tronto, Joan C. “An Ethic of Care.” Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, vol. 22, no. 3, 1998, pp. 15–20, www.jstor.org/stable/44875693.

Walton, Rebecca, et al. “Values and Validity: Navigating Messiness in a Community-Based Research Project in Rwanda.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 1, 2014, pp. 45–69, doi:10.1080/10572252.2015.975962.

Williams, Miriam F. From Black Codes to Recodification: Removing the Veil from Regulatory Writing. Routledge, 2010.

Williams, Miriam F. “A Survey of Emerging Research: Debunking the Fallacy of Colorblind Technical Communication.” Programmatic Perspectives, vol. 5, no. 1, 2013, pp. 86–93.

Weick, Karl E. “Theory Construction as Disciplined Imagination.” The Academy of Management Review, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 516–31.

Zarranz, Libe García. “Toxic Bodies that Matter: Trans-Corporeal Materialities in Dionne Brand’s Ossuaries.” Canada and Beyond, vol. 2, no. 1-2, 2012, pp. 55–68.