Anne Wheeler, Springfield College

(Published December 18, 2018)

Narratives of remembering Japanese American incarceration,[1] the forced relocation of 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II, often involve tales of unearthing, of finding artifacts and documents packed in attics and garages, of four year absences in family photo albums, and of obachans and jichans (grandmothers and grandfathers) who are reluctant to speak of their camp experiences. In the introduction to Beyond Words: Images from America’s Concentration Camps, Deborah Gesensway and Mindy Roseman describe their experience with one such unearthing and how they sought to interpret a box of artwork produced by Japanese American artist Gene Sogioka during the time he spent incarcerated in Poston, Arizona. Commenting on the variances in tone and tenor throughout Sogioka’s work, Genesway and Roseman imagine a directive issued by the artist: “Draw your own conclusions. You figure out what it must have been like to be in our shoes” (10). Because they began conducting their research on art that was produced by incarcerated Japanese American artists in the early 1980s, Genesway and Roseman were in the position to track down and interview the original artists; they were able to bring the question invoked by Sogioka’s portfolio to the artists themselves and find out what it must have been like to be in their shoes. Thirty odd years later, we no longer have this luxury. Contemporary audiences for the vast body of visual art produced by incarcerated Japanese American artists during World War II, much of which is now preserved in archives and museums, must find other methods for moving beyond aesthetic appreciation and figuring out the meaning and, in many cases, the rhetorical significance of the art.

This task is important because, as Elena Tajima Creef argues, “the representation of the experience [incarceration…] offers a particular visual narration of ‘massive American anxiety about the nation’ through the vehicle of the Japanese American body” (Imaging Japanese America 8-9). Images of incarceration show the cultural and political climate that allowed for the passage of Executive Order 9066 and the subsequent forced relocation of 120,000 Japanese Americans. While many of the most well-known images of incarceration were commissioned or at the very least sanctioned by government agencies (e.g. photography by Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams[2]), incarcerated Japanese American artists produced work in spite of the strictures and censures put in place under the auspices of Executive Order 9066.

By examining three representative examples of Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) artists and artwork—the Camp Harmony Souvenir Edition, Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660, and Jack Matsuoka’s Poston Camp II, Block 211—and, more specifically, the renderings of sanitary facilities in these texts, I consider how, by circumventing the government’s strategies for censoring images and using their art to admit viewers into otherwise restricted areas, these artists engaged in what I am referring to as tactical acts of rhetorical resistance. As I will demonstrate, the comics that these artists composed circumvented the censorship mechanisms of their original historical moments while still capturing and transmitting subversive arguments against incarceration to potentially anticipated future audiences.

I begin by reading the Japanese American experience before and during incarceration against problematic conceptions of Asian American rhetoric in order to argue for strategies of subversion rather than silence. I then borrow Michel de Certeau’s concepts of strategies and tactics in order to differentiate between acts of resistance that follow the rules and those that break them. By bringing de Certeau’s strategies and tactics together with Paula Matthieu’s reading of hope as an active process and Mira Shimabukuro’s assertion that the rhetorical-activist force of artifacts can be regenerated or reactivated, I argue that the rhetors have an agentive role in how the rhetorical purpose of their work develops over time. Having established this theoretical framework, I conduct a close reading of art by The Camp Harmony Art Department, Okubo, and Matsuoka in order to demonstrate the different possibilities for tactically subverting censors in order to contribute to public memory. As I will explain, the timing of circulation greatly affects the interpretation of artifacts and the evolution of public memories for contested events. This group of artists exemplifies how a marginalized group made savvy and effective contributions to public memory, or to what John Bodnar refers to as “those memories that emerge from the intersection of official and vernacular cultural expressions” (13). These intersections, I want to emphasize, very often include a visual representation.

Asian Americans as Resistant Rhetors

Throughout American history, Asian Americans have been coded as perpetual foreigners. Because they were not privileged with the choice to fully assimilate, xenophobic assumptions of transnationalism, ones that assumed maintaining networks with the homeland was inherently treasonous, were foisted upon them. By virtue of having the so-called face of the enemy, World War II era Japanese Americans were assumed to be participating in “ongoing economic, cultural, ethnic, and political networks and relationships” with Japan, and these networks were viewed as nefarious (Lee and Shibusawa x). Naoko Shibusawa notes, “Because of the internment, recognizing the nationalism of Japanese immigrants towards Imperial Japan has been difficult for Asian Americanists to do and, indeed remains politically risky” (259). Even for contemporary scholars, the impulse is to foreground the loyalty of incarcerated Japanese Americans while glossing over the complexity wrought by their relationships with Japan. When America went to war with Japan, in order to perform loyalty, Japanese Americans had to disavow any real or imagined connections to Japan, while at the same time their bodies were labeled as foreign and their discourse as suspect. Incarceration enforced a literal and figurative severance of the channels that informed transnational Japanese American identity and rhetorical practices. Incarcerees were considered to be neither wholly American nor wholly Japanese, and their loyalty could lay either with Japan or the United States. This choosing of sides “was a rather unnatural act, described by Issei Ko Wakatsuki as similar to having to choose between one’s parents” (Shibusawa 259). These either/or neither/nor dichotomies meant that the rhetorical practices of Japanese Americans, which drew upon American and Japanese conventions and might be described as hybridized, were inherently fraught.

In order to understand how incarcerated artists functioned within this fraught rhetorical climate, as well as how they transitioned from the decision to use art as a tactic for critiquing incarceration to the production and deployment of rhetorical artifacts, it is useful to understand the evolving understanding of Asian American rhetoric. In 1987, T. Vernon Jensen published “Teaching East Asian Rhetoric” in Rhetoric & Society Quarterly. Although the article was pedagogical in nature—it includes a week-by-week syllabus for Jensen’s proposed class—his definition of East Asian rhetoric serves as a useful starting point for considering the rhetorical expectations that might have been placed on incarcerated artists:

We have overlooked the rhetorical heritage of the East, which honors non-expression, silence, the nonverbal, the softness, and subtlety of ambiguity and indirectness, the insights of intuition, and the avoidance of clash in opinion in order to preserve harmony. We have not fully appreciated communication which highly values reasoning from authority and example, which relies heavily on analogy and metaphor. (135)

Jensen’s conceptualization of East Asian rhetoric is problematic insomuch as he attempts to impose overly specific commonalities onto a group of countries that happen to be bound together by geography and some shared cultural elements. However, and perhaps somewhat ironically, the shortcomings of Jensen’s generalizations make his understanding of East Asian rhetoric a useful starting point for considering the perceived rhetorical character of Japanese Americans in 1942.

As LuMing Mao argues in Reading Chinese Fortune Cookie, the term “hybridity,” which sometimes carries positive connotations is actually a problematic construct. For Mao, “the hybrid as a symbol of happy fusion fails to consider or discriminate those specific power relations and historical conditions that configure our encounters and determine the natures of our hybridity” (25). Jensen’s overly broad characterization of East Asian rhetoric serves as a useful example of the problems of hybridity. By imposing a false homogeneity onto a disparate group, Jensen’s conceptualization, and others likes it, provide an entry point for misconstruing rhetorical practices. As noted, whether they were citizens or not, Japanese Americans were seen as perpetual foreigners, and as such, nonverbal expression, silence, and subtlety, rhetorical characteristics admired by Jensen, were read as dangerous and sinister and seen as evidence of collusion with the enemy.

Regardless of the many ways that Japanese Americans were or were not expressing themselves, the fact that powerful entities created a culture of fear that interpreted both silence and dissent as evidence of guilt meant that Japanese Americans were in a double bind. Bill Hosokawa offers an example of this double bind in his detailed synopsis of The Tolan Hearings, which were held to deliberate relocation directly following the passage of Executive Order 9066. While recapping previous testimony during his questioning of Attorney General Earl Warren, Chairman Tolan said, “When it came up in our committee hearings that there was not a single case of sabotage reported on the Pacific coast, we heard the heads of the Navy and the Army, and they all tell us that the Pacific coast can be attacked. The sabotage would come coincident with that attack […] They would be fools to tip their hats now” (288). Chairman Tolan interpreted the fact that there was no actual evidence for sabotage being perpetrated by Japanese Americans as evidence of not only their guilt but of their acumen as spies and enemy agents.

The popular media also worked to perpetuate the characterization of Japanese Americans as silent, nonverbal, subtle, and therefore guilty. Newspaper headlines such as “Caps on Japanese Tomato Plants Point to Air Base” and “Jap Boat Flashes Message Ashore,” were not only memorable, but they credited Japanese Americans with leveraging complex visual sign systems and rhetorical patterns in order to betray the United States. In this case, the media augmented the interpretation that “the fact that nothing had happened was proof that something terrible would surely come to pass” (Hosokawa 289). Thus, Attorney General Warren’s assertion that “We believe that when we are dealing with the Caucasian race we have methods that will test the loyalty of them, and we believe that we can, in dealing with the Germans and the Italians, arrive at some fairly sound conclusions because of our knowledge of the way they live in the community and have lived for many years” can be seen as an implicit statement regarding the interpretability of more familiar, and less foreign, rhetorical patterns (Hosokawa 287).

Mira Shimabukuro offers a more culturally specific reading of perceived Japanese American silences. One way that she does this is through a focus on gaman, a “cultural ethos [that] has been noted again and again by Nisei former incarcerees as being one model of ideal behavior put forth either by their Issei parents or their teachers in Japanese school” (Relocating Authority 78). Shimabukuro offers a reading that deviates from interpretations of gaman as “a call to internalize or accept oppression without complaint” and instead suggests for “a revision of gaman’s connotation from passivity to strength” (79-80). Though Shimabukuro is careful not to collapse the multiple valences of the term, and to overwrite the experiences and understandings of those who hold alternative interpretations of gaman, by putting gaman in conversation with Malea Powell’s rhetorics of survivance (survive + resist), we can begin to comprehend how, for incarcerated Japanese Americans, the struggle to resist cannot be separated from the struggle to survive. Shimabukuro’s enactment of gaman as a show of strength allows for an interpretation of Japanese American’s rhetorical actions, which in Powell’s words, “transforms their object status […] into a subject status” (400). By stepping away from “classical” expectations of resistant rhetoric, we become much more able to listen to, and see, dynamic forms of resistance.

This representation of gaman as a rhetorical strategy recasts the silence attributed to Japanese Americans and paints the picture of a quiet rebellion,[3] one in which a quiet respect for “authority” and “example” might prevent the kind tactical rhetorical rebellion that I am attributing to the incarcerated Japanese American artists. In other words, it would be possible to read their images as documenting and respecting the status quo as opposed to making an argument against it. However, other scholarship on Asian American rhetoric, including Shimabukuro’s, has begun to develop a more nuanced understanding of the ways that Asian Americans make and disseminate persuasive meaning. Frank Chin, Jeffrey Paul Chang, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Wong’s 1991 volume, The Big Aiieeeee! An Anthology of Chinese American and Japanese American Literature offers what Morris Young has characterized as an early definition of Asian American rhetoric which seeks to, “legitimize the language, style, and syntax of people’s experience, to codify the experiences common to his people into symbols, clichés, linguistic mannerisms, and a sense of humor that emerges from an organic familiarity with experience” (qtd. in Young 70). This definition, though useful for describing and characterizing Asian American writing, doesn’t get at the fact that rhetoric, Asian American or otherwise, and regardless of modality, requires a means for action, or a way of achieving tangible action as a result of one’s meaning-making endeavors. Young, along with LuMing Mao, has subsequently defined Asian American rhetoric “as the systematic, effective use and development by Asian Americans of symbolic resources, including this new American language, in social, cultural and political contexts” (3). While this succinct definition doesn’t overwrite the editors of Aiieeeee!!’s definition, it does make the crucial move of placing Asian American rhetoric into social, cultural, and/or political contexts. Mao and Young’s emphasis on “symbolic resources” also expands the definition of Asian American rhetoric to include non-written/verbal texts, including the visual art that I examine in this article.

A key characteristic of rhetoric involves authorial intent. Though it is often easier to identify intent when analyzing examples of the written or spoken word, it is also possible to locate intentions associated with visual art. In her overview of Genesway and Roseman’s book, Beyond Words: Images from America’s Concentration Camps, Creef notes:

Japanese American artists, Hisako Hibi and Charles Mikami, each speak about the subversive potential of painting a historical record when other tools of representation are forbidden, unavailable, or underdeveloped. In place of language and cameras, both artists speak to the power of ‘talking in signs’ through painting and sketching an alternative system of visual representation that Japanese Americans were free to use in recording their individual and collective experience of relocation and internment. (Creef 71)

The fact that Hibi, Mikami, and other incarcerated artists were knowingly “talking in signs” through their work speaks to the rhetorical potential of the art. However, Creef’s characterization, in this context, of the art as “recording” individual and collective experiences runs the risk of suppressing the rhetorical and tactical potential of art produced within the incarceration centers.[4] It is my contention that by developing a complex and flexible sign system, incarcerated Japanese American artists developed a body of visual rhetoric that drew upon Japanese and American artistic and rhetorical traditions, was often humorous, and successfully subverted the government’s system of censorship. It would not be feasible to try to suggest that a single artist or even a small sampling of artists can adequately represent the incarcerated artists’ oeuvre. The Camp Harmony Souvenir Edition, Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13360, and Jack Matsuoka’s Poston Camp 2 Block 211: Daily Life in an Internment Camp are not being offered as placeholders or sole representatives for incarcerated artists. They are being juxtaposed against one another because, as a result of the similarities and differences in their training, production, representation, and circulation, they offer useful models for considering tactical acts of Asian American rhetorical resistance.

Tactical Acts of Rhetorical Resistance

In an undated and unsigned sketch of a kindergarten class in an incarceration center, eight children stand in a circle, holding hands with their teacher, whose hunched posture, traditional dress, and thin, clenched lips belie her probable age. Notably, the child directly across the circle from the teacher is drawn so that his posture mimics hers: he is hunched over, aged, and downtrodden. With a barbed wire fence drawn clearly in the background, it is hard not to see this image as a commentary on the effects that incarceration had on the traditional Japanese American social structure. Not only are the Issei and Sansei (first and third generations) collapsed into one, representatives of the Nisei (second generation) are absent from the picture.

The absence of Nisei from the sketch is notable given the strong attention paid to generational roles within Japanese American family structure. George T. Endo and Connie Kubo-Della Piana’s 1981 article, “Japanese Americans, Pluralism, and the Model Minority Myth,” an early analysis of the model minority myth, includes broad descriptions of the different challenges faced by each generation of Japanese Americans. They characterize the Nisei generation as one that sought to become “functional within the system,” and, by extension, not prone to strong acts of resistance. In other words, despite the authors’ pro-Japanese American stance, they elide the many, many ways that the Nisei responded to and resisted incarceration. Even with this shortcoming, however, they still offer useful insights into the contradictions that marked the pre-incarceration Nisei experience and note, “the Nisei upbringing was in a world of educational, social, and ideological conflict […] They were raised in a world which was simultaneously secure and confining, frustrating and challenging, and warm and hostile” (46). This representation of the Nisei as caught between binaries stems from the precarious social position wrought by being second generation. Unlike their parents, they were American citizens. Yet cultural mores of fear, racism, and exclusion kept the Nisei at the margins of white society. This marginalization was amplified by incarceration, which removed the privileges of citizenship at a time when, as Donna K. Nagata explains it, “[m]any of the Nisei were just approaching working age” and therefore it left them “without a future,” and caused them to “experience a disassociation between reality and their perceptions that they were Americans like everybody else” (17, 31).

Shimabukuro uses Nisei literacy practices to consider their experience of being caught between two cultures. She offers a brief overview of all-Japanese, Issei-produced publications that began including English language sections and of politically charged Nisei produced publications. However, despite the fact various pre-war publications sought to contribute to the identity building of the Nisei generation, “during the 1920s and 1930s the majority of Nisei were children and teenagers and may have only been marginally interested in content beyond sports or community affairs” (Relocating 61). In other words, many of the Nisei came of age in camp and, as such, they spent a time when many young adults would have been finding their voices and moving beyond “sports or community affairs” in a climate of fear, censorship, and suspicion. Seen through this lens, it is easy to understand why it would have been beneficial to appear to stay silent.

There is a common impulse to see the “disassociation” and disorientation that many Nisei experienced upon being sent to camp as an explanation for false perceptions of “the often pessimistic and docile attitude of Japanese people who did not put up much resistance in the midst of immense social injustice during World War II” (Okamura 333). However, this paradigmatic urge to read the Nisei response as silent, and thus passive, overlooks the many examples of resistant rhetoric that were produced by the incarcerated Nisei and circulated within and beyond the camps. As a generation that was accustomed to negotiating familial demands and social prejudices, the Nisei were adept at leveraging limited communicative resources to produce images that documented, represented, and resisted incarceration. They were especially well suited to draw upon various rhetorical methods in order to protest incarceration. They were skilled at working within and outside of the system in order to advocate for the rights of the Japanese American people. This is how the Nisei made powerful and multivalent arguments against incarceration.

As mentioned, de Certeau’s conceptualization of strategies and tactics serves as a useful heuristic for interpreting Nisei resistance. Broadly speaking, The Practice of Everyday Life is an exploration of how consumers interpret mass culture and make it their own. However, because de Certeau frequently positions these consumers as marginalized or subaltern, his discussions of repurposing, reinterpreting, and reimagining become useful lenses for political discourse and resistant rhetorics. Distinguishing between strategies and tactics allows for this examination, which “bring[s] to light the clandestine forms taken by the dispersed, tactical, and makeshift creativity of groups or individuals already caught in the nets of ‘discipline’” (xvii). A strategy, according to this spatially oriented model, “assumes a place that can be circumscribed as proper (proper) and thus serve as the basis for generating relations with an exterior distinct from it” (xviii). Strategies are used by the entities or institutions (established places) that yield power; they are the “official” means of communication and control. In contrast, tactics belong to the other, those that are being controlled. According to de Certeau, the tactic “has at its disposal no base where it can capitalize on its expansions, and secure independence with respect to circumstances” (xviii). Without a centralized base, tactics, and tactical actors, function from the margins, under and beyond the gaze of the dominant forces. Tactics are “clever tricks, knowing how to get away with things, ‘hunter’s cunning’ maneuvers, polymorphic simulations, joyful discoveries, poetic as well as warlike” (xviii). Strategies and tactics are articulated from within a spatial metaphor—the figure of the institution is juxtaposed against they who are not able to gain access to the institution—but through his discussion of rhetoric, de Certeau establishes a “space of language” for which “a society makes more explicit the formal rules of action and the operations that distinguish them” (xix). Language is the symbolic resource that is leveraged to enforce and resist the rules of the institution. Moreover, because for de Certeau, “[…] our society is characterized by a cancerous growth of vision, measuring everything by its ability to show or be shown as transmuting communication into a visual journey,” art joins language as a form of symbolic action that that can tactically undermine and resist institutions. Tactics, then, are a useful way of describing how Japanese Americans, such as the artists discussed in this article, staged acts of resistance outside of official conduits of communication. In order to focus on tangible compositions, as opposed to ephemeral performances, I draw from de Certeau to posit the concept of tactical acts of rhetorical resistance, which describes the production of artifacts that deliberately subverted and undermined the government’s complex network of strategic controlling mechanisms.[5]

In order to explain how tactical acts of rhetorical resistance do the work of anticipating and contributing to future public memories, we can begin by looking to the connections that Kendall Phillips makes between time and memory. According to Phillips, “The central components of the tactic—the transformation of memory of past events into rapid action at the right moment—rely on the Greek notions of mētis […] and kairos” (320). In other words, tactics are reliant on time insomuch as the efficacy of tactical maneuvers are based on timeliness—the efficiency with which a rhetor can draw from their own storehouse of memories and bring their response into being. The notion that tactics occur in “moments” is especially crucial given de Certeau’s distinction that “the intellectual synthesis of these given elements takes the form, however, not of a discourse, but of the decision itself, the act and manner in which the opportunity was seized” (xix). The decision to make art that undermined the government’s portrayal of incarceration was a tactical one, but the production thereof, as well as the artifact that came out of it, can be seen as a rhetorical maneuver. This maneuvering occurs through the deployment of improvised and subversive (i.e. tactical) rhetorical materials and methods. The development and deployment of artifacts often occur asynchronously or across time and space. In de Certeau’s words, they are on “trajectories” (xviii).

Kendall Phillips’s interpretation of de Certeau allows for the possibility that tactical acts of rhetorical resistance can possess arguments that develop over time, but it doesn’t account for the role of the original rhetor in predicting or presupposing the circumstances that allow for this development. Lacking the original rhetor’s direct testimony, it is never fully possible to determine intent; however, there are ways that contemporary audiences analyzing visual rhetoric can make sound interpretations that empower rather than overwrite the rhetor’s agency.

Hope, according to Paula Mathieu, is an active word. Drawing on Ernst Bloch, Mathieu explains that to hope is to scrutinize one’s current moment with “an eye toward a better future,” and that “hope embodies three important components: emotional desire or longing, cognitive reflection or analysis, and action” (18-19). It safe to say that incarcerated Nisei longed for or desired eventual freedom and repatriation, and that the act of drawing and recording what they were experiencing allowed for critical reflection and analysis. As Genesway and Roseman put it, “In order to paint a scene, an artist has to reflect on it, and those thoughts on and from this time remain fixed in the painting” (10). In her analysis, however, Creef successfully argues that the paintings (or other types of art that contain the artists’ reflections) aren’t solely documentary, they are “symbolic ‘texts’” and that there is “distinct visual rhetorical in the symbolic and cultural representation of Japanese American incarceration” (Imaging 9). If the work is rhetorical, then it has the potential to fulfill the role of Asian American rhetoric articulated by Mao and Young: “to bring about material and symbolic consequences that in turn destabilize the balance of power and privilege” (3). Because the artists that I am examining were incarcerated, and therefore working without the privileges of citizenship (e.g. free speech) and under threat of further restrictions, they weren’t necessarily in the position to deploy their work in a way that brought about immediate destabilization of dominant institutions. By necessity, the rhetorical activation of the work had to be delayed. As Shimabukuro explains it, “resistant elements folded into literacy,” or, I argue, art, have the “potential to relocate or ‘expand into a new activity’” (Relocating 195). She also notes, “While there is no guarantee that subsequent rhetorical acts will follow, such potential means that any written [or symbolic] activity—private and public, silent and silenced, cultural and political—can be reactivated and regenerated into further rhetorical action” (Relocating 208). By virtue of being preserved, activist rhetoric has the potential to make arguments and effect change in times and places that move well beyond the moment of production. Further, according to Shimabukuro, “People can recover cultural and political activism that was folded into and accumulated through literacy,” and, I argue, visual art (Relocating 208).

This act of recovery requires attention to context that Ruth Wodak et al. describe in the overview of critical discourse analysis included in The Discursive Construction of National Identity. For Wodak et al., understanding context involves a consideration of 1) “the semantic environment of an individual utterance”; 2) “concerns of extra-linguistic social variables and institutional settings”; and 3) “the intertextual or interdiscursive references in the text” (9-10). Put more simply, and for the purposes of considering artistic or authorial agency in reactivated or regenerated rhetorical action, context involves the time and place an artifact was produced, the institutional settings under which it was produced (wielders of de Certeau’s strategies), and how the signs and symbols contained within relate to other texts that emerged from similar or divergent contexts. Through this attention to context, it is possible to make fairly sound suppositions about the way that marginalized rhetors—in this case, incarcerated Japanese American artists—may have hoped for a future that allowed and benefitted from the circulation of dissident images. Incarcerated Japanese Americans, especially members of the Nisei generation, had the foresight and optimism to anticipate a post-war world in which the success and safety of their repatriation would rely upon their having the opportunity to tell their own story of incarceration.

De Certeau accounts for the potential slippage—in his words, mutation—that may occur when a reader from one context attempts to reconstruct meaning produced by another writer in another context:

This mutation makes the text habitable, like a rented apartment. It transforms another person’s property into a space borrowed for a moment by a transient. Renters make comparable changes in an apartment they furnish with their acts and memories […] Carried to its limit, this order would be the equivalent of the rules of meter and rhyme for poets of earlier times: a body of constraints stimulating new discoveries, a set of rules with which improvisation plays. (xxi)

By conceptualizing the reader as a tenant and the text as an apartment, de Certeau helps us see cross-temporal meaning making as an interaction; the original text was constructed by the author and thus serves as the foundation on which meaning is made. But the reader is still an inhabitant in that space, and the act of meaning making becomes a kind of temporary collaboration.

While the tactical act of creation occurs in a kairotic moment that hinges on a particular time and place, that it takes the form of a rhetorical artifact is what allows the original tactical act to be remembered and thus to transcend the constraints, censorship, and agendas of the temporal moment of production. The foresight enabled by mētis, as well as the contextual work conducted by the reader, allows tactical acts to be remembered and repurposed. Incarcerated Japanese Americans, such as the artists that I will be discussing, knew that they were being surveilled, and so I argue that they created art that both documented and critiqued their confinement. Their art could function as seemingly objective records, or even more benignly, as mere comics, but they were encoded with camp-specific signs and symbols that prove these images weren’t silent, disciplined, or obedient.

Strategic Institutions: Government Images of Incarceration

In 1943, the United States Department of War published a final report on what they termed, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast. In his foreword to the report, Secretary of War Harry L. Stimson explains, “The consideration which lead to evacuation as well as the mechanics by which it was achieved, are set forth in detail.” He also applauds the Army for the “humane yet efficient manner in which this difficult task was handled,” and joins General John L. DeWitt in pointing out that “great credit is due to our Japanese population for the manner in which they responded to and complied with the orders of exclusion” (v). The report, which consists of over 600 pages of written descriptions, charts, maps, and photographs, offers a comprehensive account of the logistics involved in removing nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans from their homes and placing them in temporary assembly centers and permanent war relocation centers scattered throughout America’s central and western states.

Among the many details outlined in this report, the following explanation of sanitation facilities is included under the heading of “Construction and Equipment of Relocation Centers”:

The laundry room is fitted out with 18 double compartment laundry trays and 18 ironing boards with an electric outlet at each board. Plumbing fixtures in each unit or block facility are hung on the basis of eight showerheads, four bathtubs, fourteen lavatories, fourteen toilets, and one slop sink for the women; and twelve showerheads, twelve lavatories, ten toilets, four urinals and one slop sink for men. (274).

|

Figure 1: "Figure 54" from Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942. |

Additionally, an image captioned “A shower room scene at Fresno (California) Assembly Center” (Figure 1), which appears 184 pages after the written description of the sanitation facilities, offers a rare photographic glimpse of the interior of a shower room. Five sets of pipes, painted white and hung vertically from a single horizontal pipe, cut diagonally across the frame. Three boys wear black bathing suits and stand in a triangular formation. Each boy covers his face with his hands and though this gesture serves the practical function of protecting their faces from the streams of water directed at them, it also renders them anonymous. The viewers’ eyes are initially drawn in by the angularity of the image, which supports the report’s portrayal of incarceration as orderly. Upon greater examination, they also notice a great deal of open space surrounding the image’s main line of sight, which speaks to the government’s message of transparency regarding the execution of necessary actions.

This kind of deliberate record keeping demonstrates that record keeping is not a neutral act (Hastings 31). The government records on incarceration, as kept by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) and other bureaucratic agencies, were carefully and systematically composed in order to make specific arguments about the necessity for and method of relocating Japanese Americans. The inclusion of photographs into these rhetorically active records achieved the contradictory effects of helping the records pass as benignly transparent and furthering their work as biased representations. The sheer volume of photographs produced—estimated at 17,000—obscured the process of subjective circulation, just as the inclusion of minute logistical details coupled with staged photographs imbue the Department of War’s report with a sense of transparency (Gordon 42). Through volume and subject matter, the official documentation of incarceration, including photographs, argued that the government had nothing to hide and supported a narrative of incarceration that focused on military necessity and humane treatment. Ironically, however, the level of censorship that was imposed on incarcerated Japanese Americans undercuts any illusions of transparency that the government’s images might have had.

Additionally, because the residents who produced images of incarceration had to do so by subverting or working around mechanisms of censorship, and therefore risking already curtailed freedom, their drawings and paintings weren’t expected to be neutral and as such, they were ultimately freer to create images that reflected not only their reality, but also their critiques of and arguments against incarceration. Incarcerated artists were able to show aspects of the camps that the government tried to censor, such as armed guards, barbed wire fences, and guard towers. Moreover, because the artists based their work on observation, memory, and imagination, they were able to depict moments and spaces that a person with a camera, even a fellow Japanese American, would not have been able to access.

This starts to explain why, in contrast to the military’s precisely rendered but relatively limited attention to camp sanitary facilities, resident-generated accounts of their time in the temporary detention centers and incarceration camps pay a great deal of attention to the community sanitation facilities. Unlike the modernity and sterility depicted in images like the shower room photograph, representations of sanitary facilities drawn by incarcerated Japanese American artists show them as overcrowded, odorous, and lacking in privacy. Whereas the government report seems to deliberately avoid making direct mention of the bodily mess that these rooms were intended to accommodate, residents’ drawings focus on the human body in a way that starkly contrasts the military’s records and, by extension, its portrayals of incarceration.

The Camp Harmony Souvenir Edition[6]

In August of 1942, as preparations were being made to move incarcerees from temporary detention centers to more permanent incarceration camps, the staff of the Camp Harmony News-Letter published a heavily illustrated Souvenir Edition commemorating time spent at Puyallup Assembly Center in Western Washington. Through short articles with titles like “Meeting the Challenges” and “Minidoka Previewed,” the textual portions of the Souvenir Edition accomplished the dual tasks of eliciting a kind of nostalgia for time spent at Puyallup and looking forward, with trepidation, to time that would be spent in more permanent facilities.

Seven full pages of illustrations depicting camp life support the publication’s nostalgic tone. With the exception of the cover page, which is comprised of a single image, and a full-page, birds-eye-view map of the center, each illustrated page consists of multiple drawings, which are framed and overlap one another so as to resemble a collection of photographs. Despite the fact that the editors of the Souvenir Edition were not able to access cameras, the publication was designed to resemble a photo spread in a contemporary magazine, or, perhaps more appropriately given that Puyallup was situated on fair grounds and framed by the peaks and valleys of roller coaster tracks, the kind of commemorative photo book that would have been sold at World’s Fairs or similar kinds of exhibitions. By drawing on the conventions of these particular genres, the Souvenir Edition created a memorial artifact that also subtly critiqued incarceration at a time when it would have been extremely perilous for individuals or groups to engage in overt acts of resistance. An unsigned editorial within the Souvenir Edition explains:

There are times that quiet suffering from trials and circumstances is an actual expression of sincerity, nobility and strength. It means as well the acceptance of a challenge to be carried through to the end in simplicity and honesty and not by artificial expressions of bravery.

It becomes the true measure by which one’s strength, nobility and sincerity are gauged. (News-Letter).

The editors offer a description of response to suffering that strongly resembles Shimabukuro’s interpretation of gaman as a kind of rebellion and show of strength by bearing up in the face of hardship. The News-Letter’s celebration of “quiet suffering” and call for accepting challenges through “strength, nobility, and sincerity,” can be read as a call to gaman, which is not a passive act. Despite the fact that the illustrations within the Souvenir Edition represent camp life in a positive light, they are still condemning incarceration. The writer’s description of gaman is the opposite of the passivity often ascribed to incarcerated Japanese Americans; at the time when it was perhaps most perilous to speak out against conditions of oppression, to gaman is to assume agency and show great strength and courage.

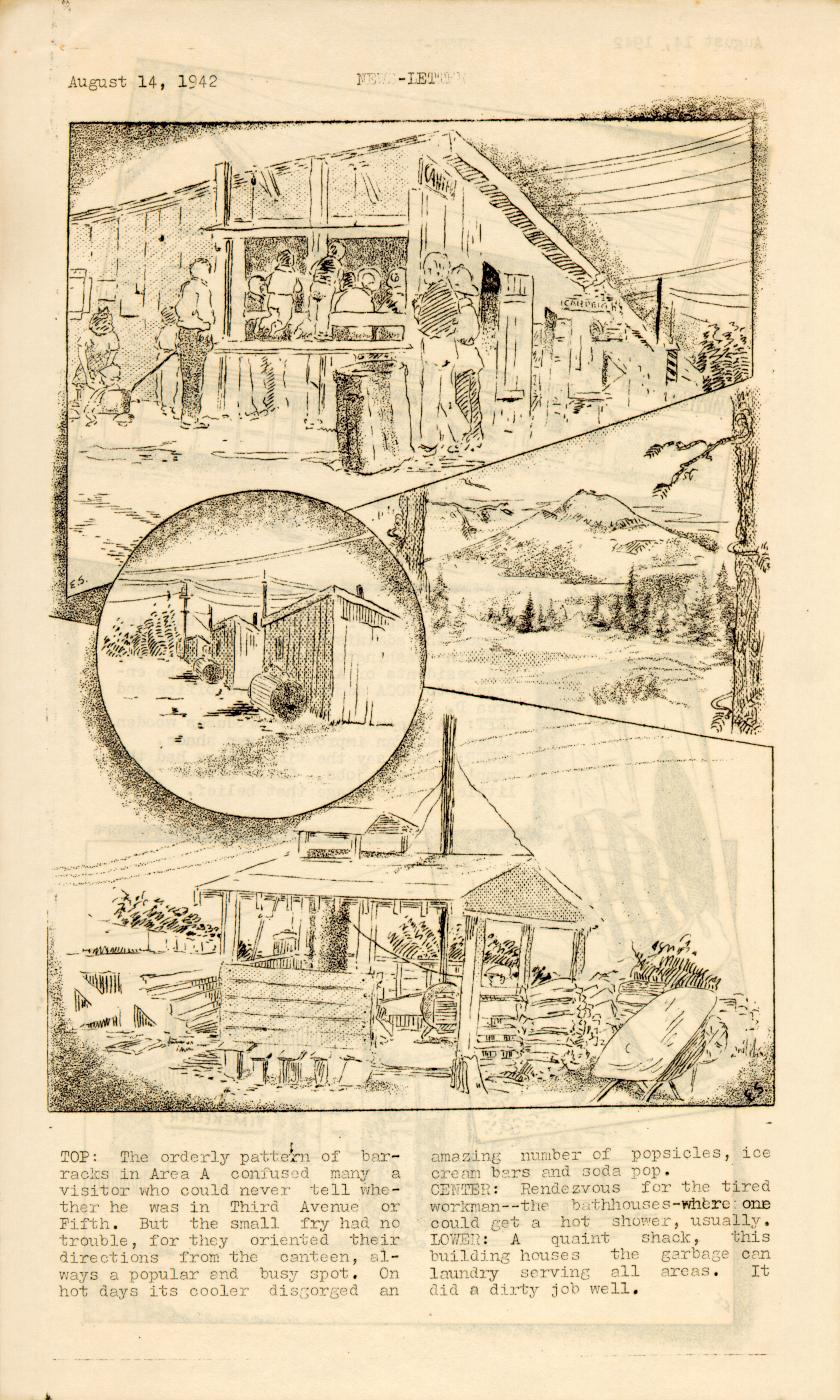

One example of this critique is through the publication’s renderings of sanitary facilities (Figure 2). The page itself is divided into thirds. A drawing of the canteen crowded with people is on the top and one of the laundry room, empty and exposed to the elements, is on the bottom. Each of these images are angled so that a borderless, triangular drawing of trees and a mountainous landscape is in the center. Finally, where the edges of the two framing images meet, and where the tip of the triangle ought to be, there is a shaded circle, with a shadow overlapping the laundry room picture, that shows the rear side of bath houses abutted by water tanks.

|

Figure 2: From the Camp Harmony Souvenir Edition. |

The natural world and the manmade camp structures depicted on this page engage in a complex interaction. The borders of the pseudo-photographs delineate the natural world as something entirely separate from camp. The Souvenir Edition differs from other drawings of camp life insomuch as it does not include any guard towers or barbed wire fences. However, through the use of connotative spatial delineation, the viewer of the page is still reminded that the people were imprisoned and not free to move between spaces. The borders represent confinement.

The sanitary facilities featured within the Souvenir Edition are shown through exterior views. They resemble neither the government’s ode to modernity and efficiency nor the other artists’ portrayal of the bodily mess associated with incarceration. At first gloss, they appear neutral and documentary in nature; however, the accompanying captions offer some insight into editorial perspective. The caption describing the circular insert drawing of the bathhouses reads, “Rendezvous for the tired workman—where one could get a hot shower—usually” (News-Letter 5). By positioning the small wooden structures as “rendezvous,” or meeting places, the viewer of the images is reminded that that within the parameters of center life, showers were not private undertakings. The reference to the lack of hot water draws attention to the tanks on the side of each building, which in light of the fact that the Puyallup housed 7,200 people, seem woefully small (News-Letter 2). The caption for the laundry room picture accomplishes a similar task of simultaneously critiquing the insufficiency of camp infrastructure and complimenting the cleanliness and quality of life that residents were still able to maintain. It reads, “A quaint shack, this building houses the garbage can laundry serving all areas. It did a dirty job well” (News-Letter 5). In this case, the description of the “garbage can laundry” explicates the image for the viewer who was not there (we are told the truth of what the residents had to work with). The fact that the laundry shack has open walls and is drawn with bleachers adjacent to it repeats the shower room motif of private actions—bathing and laundry—being rendered public. If the artists had included people within their sketches of these facilities, they would have been furthering the invasion of privacy that they were meant to be critiquing. Instead, by showing us the outside of these buildings, they comment on the lack of privacy while at the same time, offer the readers of the Souvenir Edition a reminder of the seclusion that they weren’t offered in real life.

|

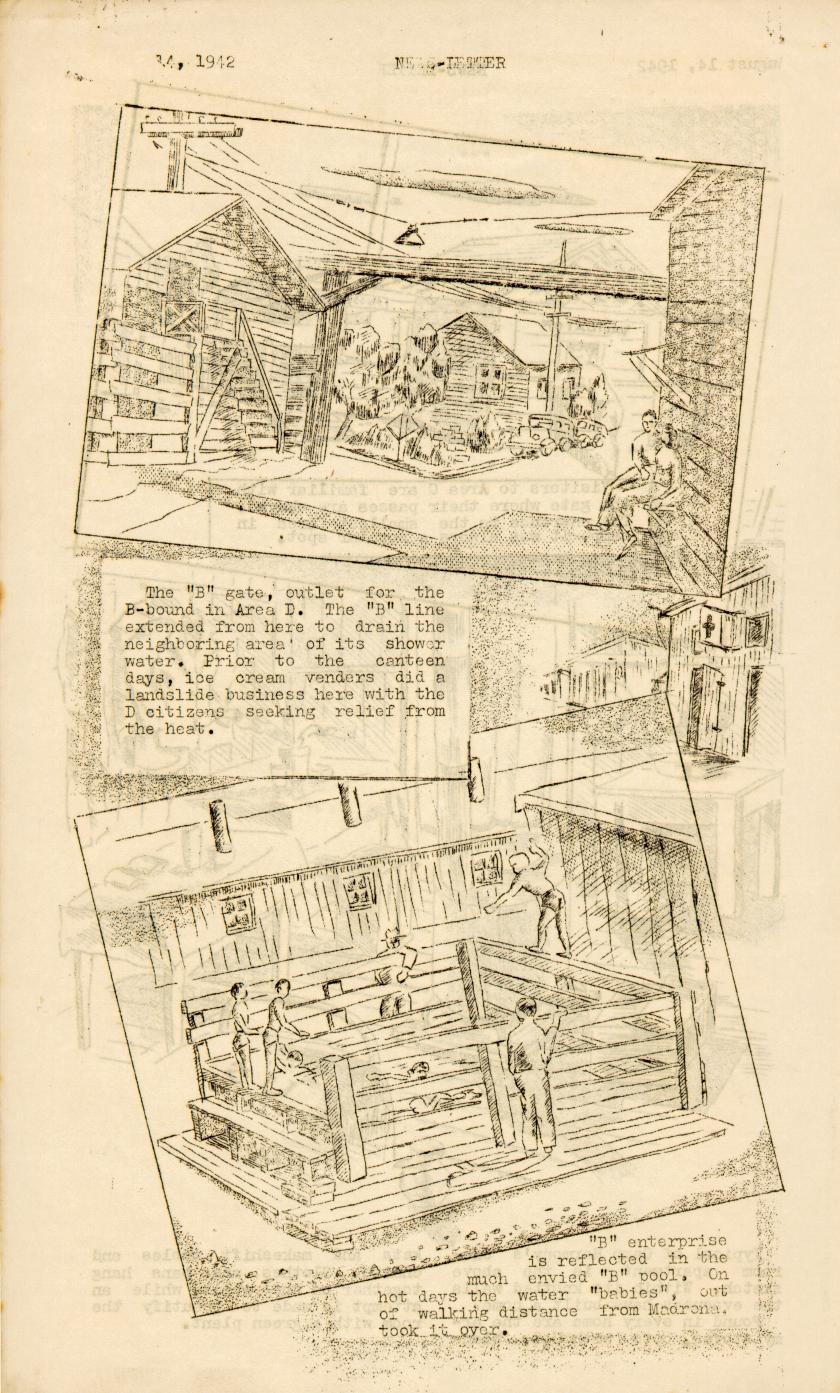

Figure 3: From the Camp Harmony Souvenir Edition. |

There is one other image related to sanitary facilities within the Souvenir Edition and its ambiguity offers valuable clues regarding the kind of remembering the publication was intended to invoke. On Page 8, three pages after the laundry room and bathhouses are shown, there is a sketch of the “B” gate, which separated that section of the camp from the “D” section. The caption reads, “The ‘B’ line extended from here to drain the neighboring areas of its shower water” (Figure 3). While the Souvenir Edition is attentive to the minute aspects of camp life, it is not initially clear why it would have been important for details of a particular drainage line to be included in the memorial artifact. Based on Miné Okubo’s renderings of residents covering their noses to avoid the smell of sewage in Tanforan and Topaz, I suspect that the drain line reference might be a heavily shrouded critique (it would have been dangerous to make overt references) of Camp Harmony’s own sewage odors, but this hunch is not necessarily corroborated by firm evidence. However, Vivian Fumiko Chin’s statement that the images in Citizen 13660 demonstrate that residents “cannot move away from the stink” and “The noxious traces, physical reality, actual presence of the living bodies of those interned cannot be eradicated” opens up a reading of the Souvenir Edition drain line references as more than minutia (30). This image must be read in tandem with the rest of the document in order for it to make sense. In the closing editorial, “Little Things,” Bill Hosokawa wrote, “And so it was the little things that made our stay at Camp Harmony memorable, little things that stood out and seemed at the time like vital milestones on the path of evacuation. But in retrospect all the little things fall into perspective, and so we shall recount a few little things which cling to memory” (9). The drawing of the drainage pipe must be viewed through the lens of Hosokawa’s call to remember the “little things,” and the various references to how insufficient shower facilities within particular blocks of Puyallup led to greater interaction between residents (four days after Area D residents started going to Area A for showers, inter-area visiting began) becomes an example of one of the “few little things which cling to memory.” While there are certainly clues throughout the Souvenir Edition that allow for outsiders to glean insight into why these minute details were featured in the publication, it stands to reason that these moments would have been much more immediately apparent for readers who received the publication during its initial circulation.

The layers of memories embedded within the Souvenir Edition offer insight into the temporal aspects of tactical acts of rhetorical resistance. In August of 1942, when the Souvenir Edition was initially circulated, the government was still in the process of fear mongering as necessary to rationalize incarceration, and as such, it was very much looking for evidence of incendiary activity. It would have been extremely dangerous to produce or circulate more overtly critical documents. However, it is likely that the spaces and moments captured by the illustrations would have been familiar to the readers of the Souvenir Edition, and the tongue-in-cheek humor embedded within the captions would have been recognizable as carefully shrouded resistance to forgetting the little things that totaled up to a large injustice. The very fact that the Souvenir Edition was filled with clues to decipher the images—in addition to Hosokowa’s editorial, “Little Things,” the final page of the publication featured “Lest We Forget,” a chronological list of important, and little, happenings at Puyallup—means that the authors made space for future audiences to engage in the act of remembering. Further, the fact that it drew on the generic conventions of the souvenir program, including the aforementioned bird’s eye view map and the collage style page layouts, means that it was successful in allowing future audiences to begin to experience the absurdity of an incarceration site being built amidst the fair ground’s permanent structures. The images and articles that lauded resident success at making due with the Puyallup facilities operated as distracting strategies that allowed the tactical critiques to pass through mechanisms of censorship. The authors of the Souvenir Edition engaged in a tactical act of rhetorical resistance by using a camp-specific rhetoric—the signs and symbols unique to the Puyallup Assembly Center—in order to create a document that transmitted their resistant activity well beyond the confines of their time and place. We don’t have access to the conversations or planning meetings that may have gone into the production of this document; we can only speculate on the tone and tenor of such meetings, and it wasn’t safe for the authors to keep a direct record. But the art is tactical and resistant. We can use it to reconstruct and remember.

Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13360

Of the artists and works studied in this article, Miné Okubo has received the most scholarly and popular attention. Okubo’s status as a Japanese American artist exemplar is marked by Amerasia Journal’s 2004 Special Issue, “A Tribute to Miné Okubo.” The issue, which was divided into three parts—“An Artistic and Literary Portfolio,” scholarly essays, and remembrance pieces—offers a holistic view of Okubo’s life and career as a self-identified artist. Vivian Fumiko Chin’s article, “Gestures of Noncompliance: Resisting, Inventing, and Enduring in Citizen 13660” offers an explicit logic for reading Citizen 13660 as resistant and, by extension, rhetorical: “If we acknowledge that the political context in which Okubo wrote her autobiographical work constructed her as an enemy who needed to be removed from a mainstream society, then we can read Citizen 13660 as a gesture of resistance that refuses to represent a compliant, invisible, and silenced Japanese American internee” (27). Moreover, Chin’s astute comparison of Okubo’s rendering of hands in Citizen 13660 as opposed to in illustrations produced for Trek: All Aboard, a literary magazine circulated in camps, successfully demonstrates the ways that Okubo may have modified or adjusted the aesthetics of her drawings in order to make different arguments for primary audiences who were situated outside of camp. By reading Okubo’s memoir as what he calls a “camp narrative,” and comparing it to written internment narratives, Greg Robinson sees it as functioning to simultaneously help Okubo work through her own feelings with regards to internment and as a platform by which she was able to “tell other ‘truths’ about internment” (50). Interestingly, Robinson also reads Citizen 13660 as borrowing the generic conventions of “photo essays of the period” but suggests that “Unlike most documentary photographers, Okubo’s strategy was precisely NOT to seem detached from any part of the internment experience” (53). Robinson’s interpretation not only nods to Okubo’s possession of the “image vernacular” of the time, it also tacitly suggests that Okubo’s text argues, rather than just testifies, about internment. Following the Amerasia Journal’s precedent to take Okubo and her body of work seriously, more recent scholarship, such as Xiaojing Zhou’s “Spatial Construction of the ‘Enemy Race’: Miné Okubo’s Visual Strategies in Citizen 13660” and Sarah Dowling’s “’How Lucky Was I to be Free and Safe at Home’: Reading Humor in Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660” offer compelling close readings of Okubo’s images and analyze the layers of meaning embedded in the text. Finally, in her 2015 article “Illustrating the Postwar Peace: Miné Okubo, the ‘Citizen-Subject’ of Japan, and Fortune Magazine,” Christine Hong looks beyond Citizen 13660 in order to more clearly illuminate “Okubo’s legacy as a wartime artist” (106). This legacy is present in texts like Naoko Shibusawa’s “‘The Artist Belongs to the People’: The Odyssey of Taro Yashima,” in which Citizen 13660 is used as the example of “graphic autobiography” that Taro Yashima’s The New Sun is defined against.

Unlike the Souvenir Edition, which was published during incarceration, artist Miné Okubo didn’t publish her graphic memoir Citizen 13660 until one year after her release from the Topaz War Relocation Center. Okubo, who was a successful working artist before internment, has commented on her choice to document her experiences through drawings:

In the camps, I had the opportunity to study the human race from the cradle to the grave, and to see what happens when people are reduced to one status and condition. Cameras and photographs were not permitted in the camps, so I recorded everything in sketches, drawings, and paintings. (Okubo qtd. in Phillips 22)

Art became the thing she could do while observing the daily activities of the camps. Citizen 13660 is comprised of pen and ink drawings, which have been described as combining the precision of Japanese line art and the detail of mural art with the comic book form (Phillips 22). The conflation of Okubo’s influences—her mother was a classically trained Japanese artist, Okubo worked with Diego Rivera on WPA murals prior to internment, and once in the camps, she was a frequent reader of daily comic strips—combined to form a uniquely Asian American artistic style (Yamada 22-23). The memoir itself proceeds chronologically and offers detailed images and description of daily life. The reader is left with an overall impression of Okubo’s camp experiences, a mixture of anger and melancholy, which is inseparable from her tactical critique.

One of the most distinctive features of Citizen 13660 is the way that Okubo portrays herself within the images. She is present in every frame and always drawn so that she is either staring directly at the subjects in the frame or, less frequently, looking directly out of the frame as though attempting to make eye contact with the reader. This bold breaking of the fourth wall is a notable rhetorical act for multiple reasons. First, in contrast to the collaborative authorship of the Camp Harmony Souvenir Edition, the assertiveness of the gesture stands in direct contrast to conceptualizations of Asian American rhetoric that would have the rhetor bowing to the authority of established power relations and abiding by cultural conventions. Additionally, in “Portrait of an Artist,” a 1942 profile of Okubo published in Trek: All Aboard, an incarceree-produced literary magazine, writer Jim Yamada explains Okubo’s prewar experiences travelling in Europe and her transformation from a “shy mouse” to a “character”:

It embarrassed her at first to have street cars in Holland jerk to a stop so that people in them could have a better look at her; she was a cynosure wherever she went, once causing a terrific traffic jam in a Belgium town. Her first impulse was to run to the nearest unpopulated alley when the natives gawked at her, but she conquered this, and, instead of retreating, she stared right back. She made a lot of friends this way, in addition to deriving tremendous amounts of self-confidence. (21)

|

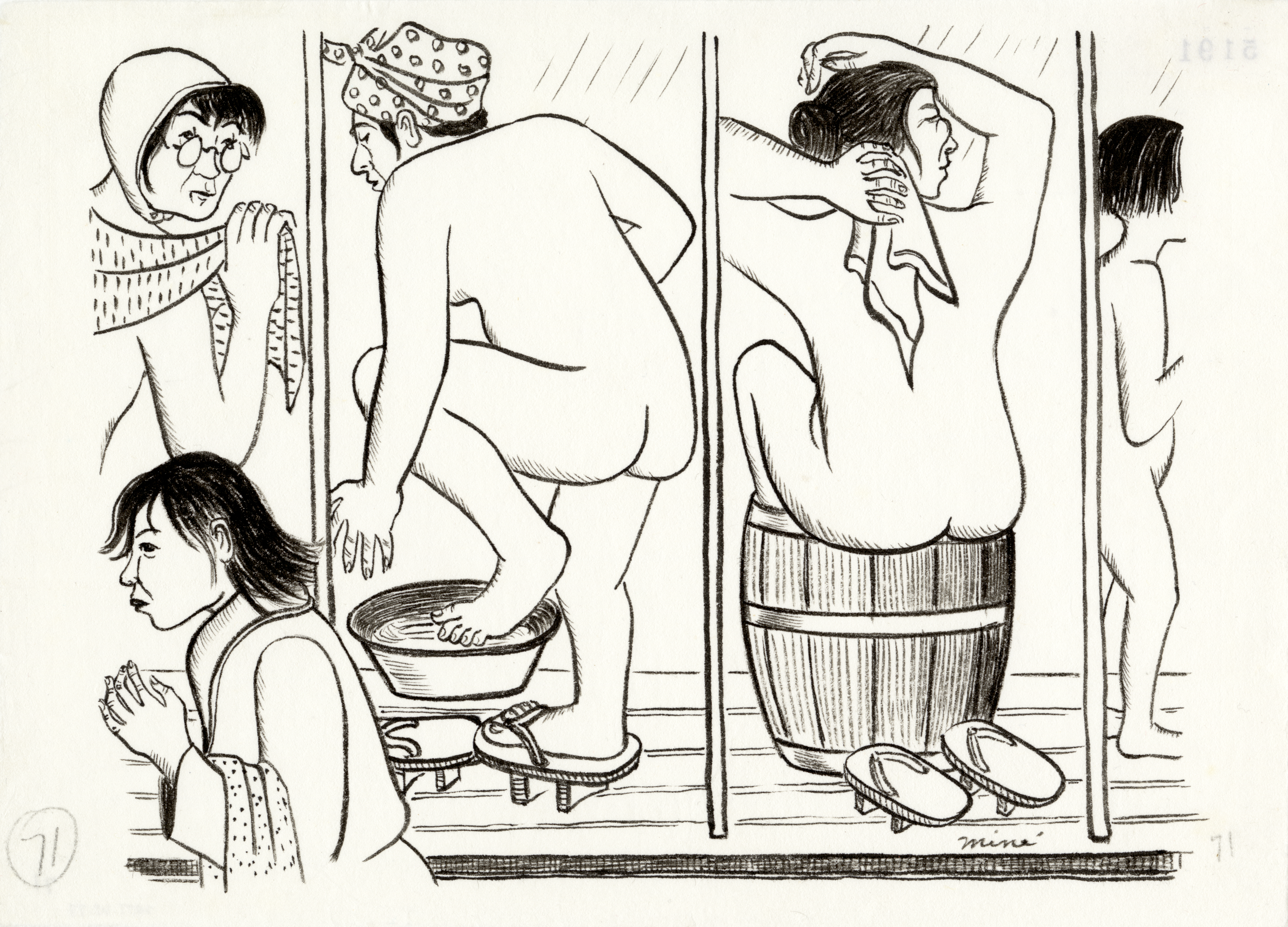

Figure 4: From Citizen 13660 |

This self-confidence radiates from the page (Figure 4). Okubo’s stare acknowledges the presence of a viewer and thus acknowledges the voyeurism invoked by the depiction of a bathing scene. Like the memoir itself, Okubo’s personal experiences coalesced into political action. This staring back strongly contradicts expectations that Asian American rhetoric be indirect and “avoid a clash in opinion in order to preserve harmony” (Jensen 135). As Yamada’s profile makes clear, Okubo overcame her instincts to avoid clashes and deliberately cultivated a way of interacting with the world that contradicted with her internal instincts and externally imposed rhetorical assumptions.

In the bathing image, the frame is bisected by an off-center dividing wall and Okubo places her own naked figure, staring out of the frame, to the far right. The left side of the frame is filled by a mother hunched over the tub, bathing four small children. The emptiness of Okubo’s side of the frame is juxtaposed against crowding and motion to the left. The image simultaneously portrays the lack of privacy inherent in camp life, in which the viewer is complicit, the challenging conditions under which individuals operated, and the fact that the functions of “normal” life, such as bathing oneself and one’s children, still went on.

The significance of Okubo’s depiction of herself in the tub becomes more apparent when considered in conjunction with the rest of the images of sanitary facilities included within Citizen 13660. In every other shower or toilet scene, Okubo is fully clothed and positioned in the frame as an observer. The fact that she is now the one exposed, while the only other adult figure in the frame is dressed, speaks to the fact that she has grown accustomed to camp life. Additionally, the emptiness and stillness of her side of the frame, as opposed to the fullness and business to the left, suggests the odd role that young, unmarried, Nisei played in the camps. Stripped of clothing and the trappings of adulthood, Okubo appears childlike, but unlike the children to her left, she has no caretaker. This image exemplifies the ways that incarceration upended the Japanese American family structure and how Nisei lives in particular were rendered adrift by years of disruption.

In order to consider the image rhetorically, it is necessary to extricate and examine the specific moves that Okubo makes within the image. The bisecting wall is a repeated motif throughout art produced by incarcerated Japanese American artists. The walls represent the crowded conditions and a lack of privacy within the camps. They also become sites of illicit listening or watching, sometimes by Caucasian officials and sometimes by other incarcerees. Additionally, it is not uncommon for traditional Japanese woodcut art, such as the Sumizuri-e (monochrome) tradition, which Okubo’s drawings resemble, to feature subjects watching over walls and from behind screens. Within the specific context in which Okubo was working, the wall is a symbol of and comment on confinement and constrained living conditions. Okubo, and other artists that utilize this motif, developed a sign system that was simultaneously specific to the camps and that drew upon a larger artistic and symbolic tradition. Notably, the shape of the mother’s body on the left side of the frame resembles the scores of oval shaped bodies that appear throughout 19th century woodcuts. Her eyebrows are arched and shaded in a way that is reminiscent of Kabuki actors, but the traditional kimono is replaced by the modern, western cut dress and apron. Combined and re-contextualized, these elements coalesce into a single image that both documents and argues against the confined living conditions in the camps.

Aside from the aesthetic influences of Sumizuri-e observable within Okubo’s work, it is difficult to ignore the influence of Diego Rivera, whom she assisted on the Pan American Unity Mural as part of the “Art in Action” exhibition at the 1940 World’s Fair. Rivera featured an image of himself, the painter within the mural, participating in the making of art and meaning.

In another bathing image, Okubo appears in profile against several women washing, giving themselves what appear to be sponge baths (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5: From Citizen 13660 |

In this picture, Okubo the artist is looking but not looking. The rounded figures of women bathing seem to exist, flatly, behind Okubo’s profiled figure and are reminiscent of Rivera’s murals insomuch as the subject of the work and the making of the work collapse upon one another and become inseparable. Through the paradigmatic inclusion of herself in her images, observing that which she renders on the page, Okubo suspends the tactical encounter in time. The kairotic moment of observation is captured through Okubo’s inclusion of herself in her drawings. She is simultaneously recorder and subject.

The reflections of Japanese artistry and Rivera’s influences in Okubo’s work combine to form a Japanese American rhetoric. Okubo’s tactical choice to embed an argument about maintaining tradition and humanity in the face of confinement and severed civil rights into documentary artwork ensures the rhetorical nature of the artifact. The images of sanitary facilities, specifically, make transparent the fact that incarceration camps dealt in bodies and the viewer’s discomfort at being rendered voyeur becomes a way of affectively experiencing Okubo’s argument. Like the Souvenir Edition, Okubo’s work allows for the reconstruction and remembering of camp life. By being made uncomfortable by Okubo’s rendering of her gaze, the viewer of the image has a moment of identification with the feeling of camp. That which cannot be fully recreated, the ongoing exposure of one’s body and the stripping of their rights, is temporarily resurrected. The scales of the experiences differ—looking at an image and living through an experience—but the effect on public memory is still tangible.

Jack Matsuoka’s Poston Camp II, Block 211

Jack Matsuoka’s work looks very different than Okubo’s or the Souvenir Edition. He was only fifteen at the beginning of incarceration, and the original sketches included in Camp II Block 211 were produced during his time in the camps, but he redrew them prior to book’s 1974 publication. Although he worked as a professional cartoonist for much of his career, he was drafted into the army after spending one semester of art school and presumably didn’t receive the extensive artistic training that Okubo had. His lines are looser than Okubo’s, and he uses comic book conventions like the speech bubble, odor lines, and sweat beads to augment his pictures’ messages. In the text leading up to a comic about an exchange held in a laundry room (Figure 6), which Matsuoka wrote after incarceration and specifically for the publication of his book, he notes:

The laundry room as the great leveler.

No matter what their social position or wealth on the outside, in camp all of the ladies had to use the same laundry room to do their washing—by hand. (92)

|

Figure 6: From Camp II Block 211 |

Although Matsuoka’s written cue is helpful for introducing that section of the text, it is not as strong as the visual argument made in his actual drawing. The woman to the left, smoking a cigarette, represents a modern and thoroughly middle-class American way of living. Her off-handed comment that her family’s maid “kinda looked like you [the woman to the right]” speaks to the fact that the incarcerated Japanese Americans were not as homogenous as the WRA made them out to be. The woman on the right’s smoldering expression—shown through furrowed eyebrows and a down crossed mouth—also speaks to this perception of difference. Though the circumstances of camp forced these two women to do laundry within the same facilities, they did not see one another as the same and they resisted forced notions of homogeny.

The obvious anger and discomfort being expressed by the woman on the right offers a crucial rebuttal to whitewashed depictions of camp life. Carey McWilliams’s depiction in the September 1942 edition of Harper’s Magazine is paradigmatic of the descriptions Matsuoka’s comic critiqued. Despite the magazine’s notorious left wing stance, and McWilliams’s initial opposition of incarceration, he offers a series of rationalizations for why the “evacuation” was in the incarcerees’ best interest. Alongside various statements regarding Japanese Americans’ failure to fully assimilate into American society, McWilliams writes,

In general, however, I believe it correct to state that many of the camp residents, perhaps a third of them, are living better than they have ever lived in their lives; that another group, also perhaps a third, made up of relatively well-to-do families, are unquestionably having a difficult time in adjusting to the new routine. A definite leveling off process is discernable, in fact, in all camps. (363)

McWilliams’s description of a “leveling off process” is reflective of Matsuoka’s description of the “laundry room as the great leveler.” This suggests that McWilliams was not entirely incorrect in suggesting that the camps may have challenged the pre-existing Japanese American social hierarchy, despite his sweeping claims regarding quality of life, manufactured statistics, and assumption that access to “modern” conveniences might be worth the suspension of one’s civil liberties. However, among the key differences in these two representations of social class leveling is that Matsuoka’s was delivered with the kind of wry humor that can often be seen in Asian American rhetoric. The comic book lexicon allows the woman on the right to resist any assertion that she might be better off than she was. Instead, it allows her to express anger.

Matsuoka’s images employ rhetorical strategies that bring to mind the The Big Aiiieeeee!’s characterization of Asian American writing and sensibilities highlighted by Young, which emphasizes the codification of “experiences common to his people into symbols, clichés, linguistic mannerisms, and a sense of humor that emerges from an organic familiarity with experience” (Chin et al. qtd. in Young 70). By creating two characters that represented radically different social classes and lifestyles, Matsuoka generated symbols of Japanese American heterogeneity. Additionally, the visual links between Matsuoka’s images and comic drawings bring a sense of humor to bear on his arguments regarding incarceration. In contrast to the careful construction of Okubo’s frames, with their myriad layers of meaning, and Japanese, American, and Asian American influences, Matsuoka’s images are messier and convey a sense of movement.

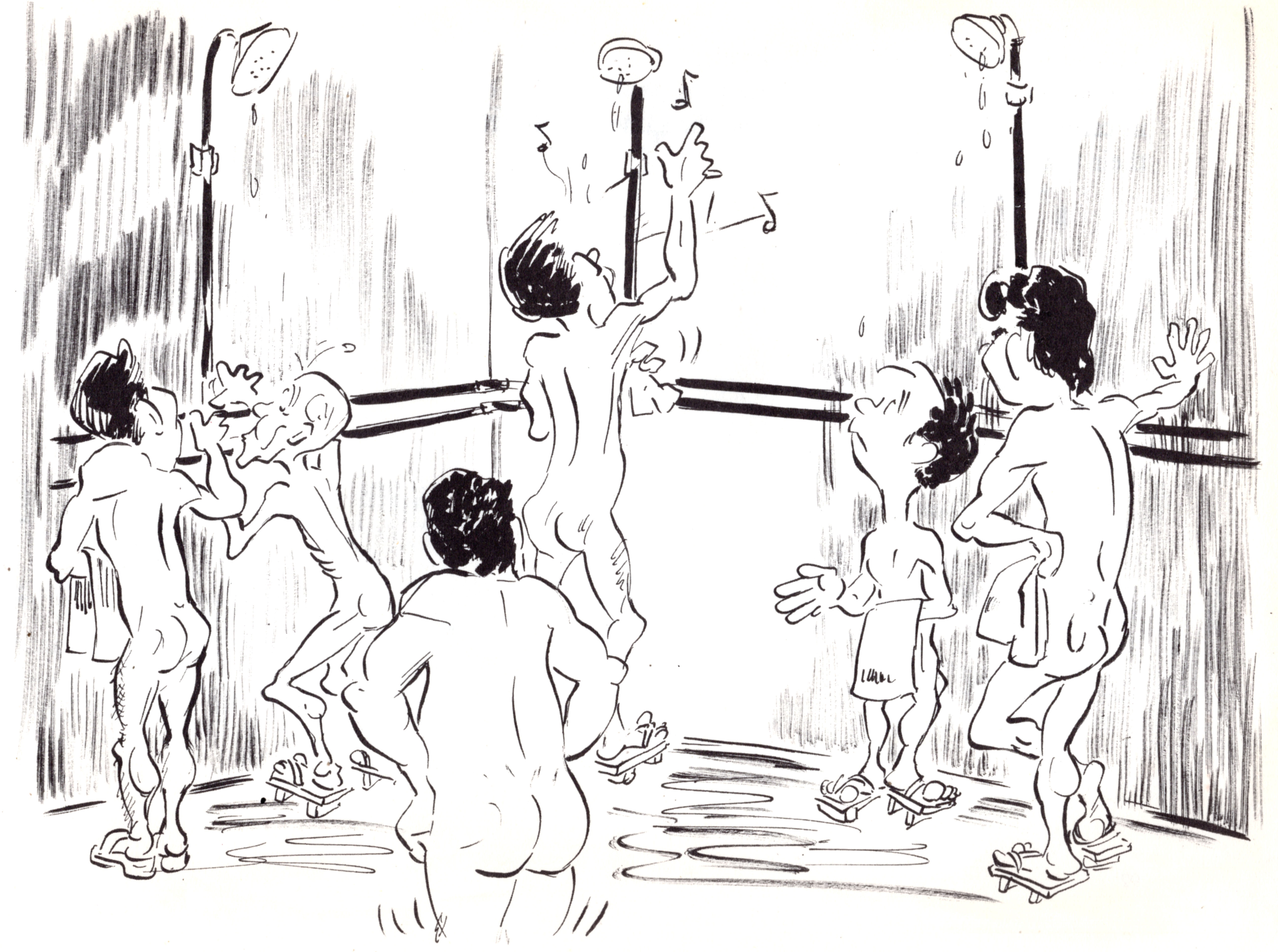

Unlike Okubo’s bath and shower scenes, which are rife with images of women and children, Matsuoka’s depiction of the shower room invites the viewer into a decidedly masculine space. The drawing captioned, “The world’s only almost dry shower,” shows a group of men whose bodily tasks are interrupted by technological failures (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7: From Camp II Block 211 |

The two men on the left appear to be trying to fiddle with or fix the tap, while the two men on the right look on. The man at the center shower engages vigorously in the act of washing while apparently singing or whistling a tune. He is unaffected by the relative lack of water being produced by his shower head, and as such seems to be following an exaggerated version of the code of gaman. Unlike the other men in the shower room, the singing man appears to be “bearing up” against the hardship that has derailed the others. As Shimabukuro makes clear, it would be easy to misinterpret or oversimplify this bearing up as a rhetorical strategy of non-resistance, but Matsuoka’s cartoon illustrates the strength of such an action (“Me Inwardly” 651). By featuring the singing man as one reactor amongst several, Matsuoka reinforces his argument that though incarcerated because of a common ethnic background, the Japanese Americans were as varied as any group of Americans. The range of body sizes and postures included within this image offer a visual underpinning for Matsuoka’s arguments regarding the heterogeneity of the incarcerated subjects.

Deploying Comics for Rhetorical Purposes

As I have demonstrated, the art that I discuss in this article all contains elements that with varying degrees of subtly critiques the premises and terms of incarceration. Moreover, by drawing upon and developing a sign system comprised of elements of popular culture and images unique to camp life, the works fulfill the first part of Mao and Young’s definition of Asian American rhetoric, “the systematic, effective use and development by Asian Americans of symbolic resources, including this new American language, in social, cultural, and political contexts” (3). However, the second part of Mao and Young’s definition, which states these symbolic resources are deployed in order to “bring about material and symbolic consequences that in turn destabilize the balance of power and privilege” cannot be ignored (3). When reading these comics as examples of tactical acts of rhetorical resistance, we must consider how and when the work went from documentary to rhetorical, and what role the original artist played in the deployment.

Although the Camp Harmony Souvenir Edition was circulated during the early days of incarceration, in August of 1942, when the scope and outcome of the war were not yet known, its authors presupposed the need for it to serve as a memorial artifact after incarceration. In an editorial “Our Coming Hurdle,” which is printed parallel to Hosokawa’s “Little Things,” James Sakamoto[7] writes, “Let us not forget that our record hear will speak for us during that difficult period of rehabilitation that must follow the end of the war.” He anticipates, in no uncertain terms, a post-war United States in which the Souvenir Edition would be called upon to represent the Japanese American experience. Taken in tandem with the visual images through the volume, it is clear that the Editorial Board and the Art Department anticipated a future in which their perspective on incarceration would be safely heard; the critiques shrouded in the drawings, the wry commentary, and the performance of gaman all speak to the rhetorical legacy that they were looking to build.

When producing the drawings contained within Citizen 13660, Okubo also was aware that she was using her drawings to circulate the intimate experiences of camp life beyond the time and space of incarceration. As she described it:

All my friends on the outside were sending me extra food and crazy gifts to cheer me up. Once I got a box with a whole bunch of worms even. So I decided I would do something for them. At the time I wasn’t thinking of a book; I was thinking of an exhibition, but these drawings later became my book Citizen 13660. So I just kept a record of everything, objective and humorous, without saying much so they could see it all. Humor is the only thing that mellows life, shows life as the circus it is. (Okubo qtd. in Gesensway and Roseman 71)

Okubo created her drawings for public circulation. While she stated that her work was objective record, the fact that she also sought to make the record humorous demonstrates that she was including her own stance and perspective in her representations. However, Citizen 13660’s rhetorical activity isn’t limited to functioning as a humorous interpretation. In her analysis, Creef offers insight into the text’s symbolic consequences. For Creef, Okubo’s choice to include herself in every drawing means that she “not only aligns herself with the collective Japanese American community, but makes herself the subject of her own discourse and, in the process, inserts herself into the text, and into American history” (“Going Her Own Way” 85). Seen as a tactical act of rhetorical resistance, Okubo created a wartime record that presupposed the need for the experience of the other—Japanese Americans, women, Nisei—to be included in the historical record.

Of the three examples discussed in this article, Matsuoka’s work probably has the most pluralized moments of rhetorical deployment, which speaks to the dynamic nature of resistance. In his explication of tactics, de Certeau writes, “because it does not have a place, a tactic depends on time—it is always on the watch for opportunities that must be seized” (xviii). The tactical act is marked by the decision to seize a moment, “the act and manner in which the opportunity is seized. A review of the history of Poston Camp II, Block 211 reveals three distinct moments in which Matsuoka seized a moment and how the conditions of this moment affected the rhetorical purpose and force of his work. The first moment occurred in camp, when he generated the original drawings and developed the basis of his critique. However, due to the constraints of his situation—not only was he incarcerated, he was also 15-years-old—he did not circulate the work. The next tactical moment occurred in 1974, after his mother found the drawings in a trunk and encouraged Matsuoka to circulate them. Edison Uno, a Nisei civil rights advocate, documented a clear recollection of the moment: “When I first met Jack and saw his collection of old camp cartoons, I immediately envisioned the possibility of compiling them into a book for use as an important educational tool in the primary grades. It was not difficult to convince Jack” (“Jack Matsuoka: Using Cartoons to Tell the Story of Camps”). In response to these suggestions, Matsuoka re-drew the original cartoons, added captions, and put them in a specific order. Through these actions, Matsuoka tacitly authorized the rhetorical potential of the original cartoons, and by reproducing and circulating them thirty years after they were originally conceived, he reactivated them for the purposes of supporting the Redress movement. In 2003, Matsuoka collaborated with his daughter, Emi Young, and received a grant to not only republish his book but to develop a social justice oriented curriculum guide for school children. As described by Megumi, the storyteller that Matsuoka and Young worked with, his work inspired her to stand up to up to injustice in any form (“December 18”). By examining these three tactical moments, we can see how the richness of the original images, and the critiques embedded within them, allowed for multiple acts of rhetorical resistance.

The fact that Matsuoka was able to delay circulation and protract his tactical moment to thirty years and then sixty years after the moment of production can be attributed to the powerful relationship between tactics and mētis. As de Certeau explains, “Mētis in fact counts on accumulated time, which is in its favor to overcome a hostile composition of place. But its memory remains hidden (it has no discernable place) up to the instant in which it reveals itself, at the ‘right point in time’” (83). Given the depth of his images, Matsuoka encountered multiple “right points in time.” At the time of their production, Matsuoka was an incarcerated teenager struggling with his lack of freedom. At the time of their first circulation, Japanese Americans were beginning to seek redress for incarceration and to permanently embed the atrocities into the American memory. By then, Matsuoka was a middle-aged man looking to put his previously uncirculated artwork to use; he was ready for it to make an argument. By the time of their second circulation, Matsuoka was 78-years-old, and the post-9/11 landscape was fraught with anti-Muslim sentiments and an ever expanding international conflict. Thus it is possible that the tactical moment can be pluralized (moments) while the rhetorical artifact remains static and relatively unchanged.

The Camp Harmony Art Department, Okubo, and Matsuoka all produced texts that are linked by shared subject matter and purposes. Despite these similarities, they brought very different stylistic choices to their work and employed different tactics when producing and circulating their work. They were also only a few of many of incarcerated artists working diligently to document and resist the conditions of incarceration. By classifying this art as rhetorical, I recast the incarcerated artists as agentive meaning makers who actively worked to document and resist injustice for which present and future representations were being closely controlled by the government. Where the censors tried to sanitize camps, the incarcerated artists messed them up. Where propaganda attempted to create a homogenous enemy, incarcerated artists rendered their own versions of the collective that featured individuality and difference.

By framing these works as tactical acts of rhetorical resistance, not only is the complexity of the art revealed, but we can also credit the artists for the symbolic consequences that their work achieved and will continue to achieve. While the interpretation and deployment of this work sometimes involves, in de Certeau’s words, a temporary tenancy by an interlocutor, the credit for producing this multiplicity of viewpoints belongs to the incarcerated artists and their tactical acts of rhetorical resistance. They were the ones who seized the kairotic moment. They knew that their experience would need to be documented and argued against from their own perspectives, and so they drew what they saw. The drawings weren’t neutral; they tactically resisted the censors by putting in references, images, signs, and symbols that the government would not understand. Viewing the two women in the Matsuoaka’s laundry room, the government censor would, presumably, not see the difference between the two women; meeting Okubo’s gaze in the bathroom, the censor would focus on nudity and signs of subterfuge, not lamentation for a lost generation; and the neat lines of the Souvenir Edition would bely the success of an unfortunate necessity and not the critique of forced confinement. By framing these protests as tactical acts of rhetorical resistance, I credit these artists with having a pretty strong sense of what they were doing. They were resisting the conditions of their confinement and asking future audiences to insert their experience into the public memory of incarceration: messy, unjust, and unnecessary.

[1] In keeping with the recommendations made by the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), I use the term incarceration in order to avoid engaging euphemistic language that dilutes the injustice of these events. Given that the terminology is contested, however, when summarizing or quoting from other authors and speakers, I move away from my own politics of language and replicate their preferred tonal choices.

[2] See Thy Phu, Jasmine Alinder, or Elaina Tajima Creef for scholarship analyzing wartime photography of incarceration.

[3] Gaman is a complex term, and by offering this definition, I don’t want to collapse its nuances. Depending upon one’s individual interpretation, “bearing up,” for example, can carry positive or negative connotations.

[4] In Imaging Japanese America, Creef firmly situates visual art as rhetorical.