Karrieann Soto Vega, University of Kentucky

(Published September 21, 2020)

If you don’t know why we need a collection on “rhetorics elsewhere and otherwise,” then you need to pay more attention. In the year that has transpired since the publication of Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise: Contested Modernities, Decolonial Visions (2019), several events have demonstrated that institutions continue to exclude and hurt minoritized populations. Perhaps you have seen the news about the dehumanizing treatment of migrants attempting to cross the US/Mexico border, or the egregious state-sanctioned murders of Black people by police and other militarized branches of the government, or the glaring inequities in healthcare access for Indigenous and other people of color. Within this context, a reckoning with racialized violence in the academy has taken the form of hashtags like #Blackintheivory. Manifestations of the kinds of stories included in the #Blackintheivory hashtag are prevalent in Rhetoric, Composition, and Communication. For instance, when the National Communication Association (NCA) decided to select Distinguished Scholars through a process that would account for diversity and inclusion, several of the scholars already awarded that title—all of whom are white—expressed concerns that “diversity” would undermine “merit.” Colleen Flaherty aptly described the controversy as one in which “white scholars pick other white scholars.” The debate highlighted the insidious white supremacy in Communication as a field.

The need for decolonial projects is dire.

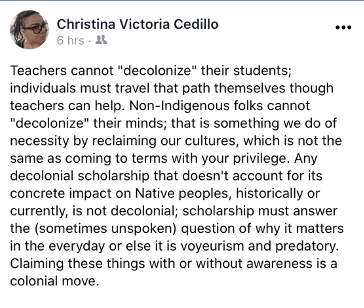

Figure 1: Social media statements by academics referring to decolonial moves.[i]

As evident in the social media posts included above, calls to decolonize multiple aspects of the academy are not uncommon. In fact, several recent books ask us to consider ways of Decolonizing Academia (Rodríguez), Decolonising the University (Bhambra), and Decolonizing Methodologies (Smith). But what does it mean to “decolonize?” Some think the term means adding non-white voices to our syllabi, curricula, research, and maybe even our department—and if you’re really radical, perhaps upper-level administration. Others contend that decolonial projects ought to be concerned not simply with diversity and inclusion, but also with Indigenous land redistribution and what that process would entail for those enveloped in settler colonialism (Tuck and Yang). Indeed, it may be difficult to assess where to start decolonizing, especially since there is a wide array of definitions for the “decolonial” concept that impact the political project carried out under such a banner.

One of the significant contributions that Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise makes is in the opening chapter wherein García and Baca survey the ways decolonial perspectives have become prevalent in the humanities. In particular, García and Baca assess how Writing and Rhetoric Studies (WRS) could potentially benefit from such work. They delineate an extensive genealogy of thought in WRS that attends to coloniality for confronting hegemonic perspectives (mainly white male Eurocentric canons in the field). Alluding to postcolonial orientations, the authors note that even as they include stories from scholars who analyze “colonialism and coloniality from a different period in time,” there has not yet been a decolonial resolution. Therefore, García and Baca acknowledge that Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise is an incomplete project, with the chapters mired in “stories-so-far” (14). I agree that the project would have to be considered incomplete: as long as colonialism exists in its many iterations, we will need decolonial visions that attend to coloniality, extractive colonialism, and settler colonialism as distinct but related structures.[ii] Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise joins a list of calls for solidarity among other academics working towards the liberation of a colonial territory, which includes the academy and its people (Grande; Mohanty). However, Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise could have done a better job of approaching decolonial work through a more explicit commitment to solidarity with decolonization previously expressed by Indigenous scholars—such as questioning our relationships to diverse body- and geo-politics and including our positionalities as settlers.

As a discipline, Latinx Rhetoric and Composition has tended to take up decoloniality as an analytical framework rather than focusing on decolonization as a goal, which has been a more explicit priority for American Indian and other Indigenous scholarship. Nodding to but differentiating from the decolonial project that attends to land and resource redistribution, García and Baca distinguish decolonization from decoloniality, expressing a preference for the latter. Informed by the Modern/Colonial Group school of thought and drawing heavily from the work of Argentinian philosopher Walter Mignolo, García and Baca contend that an attention to decoloniality highlights and works against the epistemic conditions that give rise to hegemonic power afforded by, and embedded in, colonial processes. This view reflects many of the panels I attended during the Cultural Rhetorics Conference in 2018, especially by some of the presenters who contributed to Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition Studies: New Latinx Keywords for Theory and Pedagogy (Ruiz and Sánchez). Although García and Baca cite the work of other Indigenous scholars, I noticed their preference for decoloniality resonates with Malea Powell’s “2012 Chair’s CCCC Address: Stories Take Place: A Performance in One Act” inasmuch as she invokes Mignolo. Yet Powell reframes decoloniality as a way to address the need for decolonization by acknowledging the Indigenous stories of the places in which we gather for our scholarly endeavors, which is missing in Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise. What all of these works share is a decolonial aspiration for Rhetoric and Writing, for all of those who have been relegated to a marginal position based on their subjective epistemologies and ontologies—that is, their ways of knowing and being.

In my own decolonial approach for Puerto Rican peoples both in the Caribbean and in the diaspora, I take up an expansive conception of decolonial work that includes decoloniality while still striving towards decolonization. In this approach, decolonial work is not limited to teaching writing (though education is our frontline work). Rather, this work also includes learning from and contributing to mutual aid efforts preventing peoples’ deaths in a context of state disinvestment (Soto Vega), as well as support for grassroots activism to acquire and protect land and oceanic territories at risk of transnational corporate development, such as a mega resort ironically named Columbus Landing. In Puerto Rico, there are simultaneous iterations of epistemological coloniality, extractive colonialism, and settler colonialism, which explains the need for an expansive conception of decolonial work. For Puerto Ricans and other Latinxs who engage in forced migration to the contiguous United States, it is necessary to act in solidarity with decolonization efforts in the places we now call home, as we are enveloped within existing settler colonial structures. Like Sandy Grande, I am devoted to the “possibility for building co-resistance movements between Black radical, critical Indigenous, and other scholars committed to refusing the settler state and its attendant institutions” (172). Grande was writing in 2015, as the Black Lives Matter movement was forming. In the summer of 2020, the most recent movement for Black lives has proven to be another kairotic moment to continue building co-resistance.[iii]

In order to build co-resistance, scholars ought to attend to the ways our decolonial approaches correlate while acknowledging specificity and heterogeneity. The benefit of an edited collection like Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise is that it provides a variety of voices that coalesce around a similar goal (articulating a decolonial vision from specific perspectives) while also demonstrating the heterogeneity of such perspectives in terms of methodology. As editors, García and Baca aim to uplift the scholarship of those who address how, as they explain, “an ‘otherwise’ local epistemology works to reinscribe the geo- and body-politics of knowledge and understanding that has been repressed and oppressed or that is still colonized as a result of hegemonic models of thinking” (4). It is certainly reassuring to encounter a collection of scholarly work that does not simply problematize the coloniality inherent in the normative knowledge that disciplines Rhetoric and Composition, but one that also provides methodological tools to engage the re-creation and re-centering of subjugated knowledges from marginalized “others” in the field. Throughout the book, there is discussion and use of ethnography (Viera), autoethnography (Alvarez), intersectional reflexivity and historical material methods (Arellano and Ruiz; Callafel and Ghabra; Sharma), discourse analysis (Chrifi Alaoui), and performance as archival work (Browne). Besides the arsenal of methods that enculturation readers may find familiar, in all of the chapters the writers explain their approaches by accounting for the ways their positionality informs their research. That is, each author provides a unique perspective on the “geo- and body- politics of knowledge and understanding of local histories situated across the globe” and on the ways they each approach their articulation (García and Baca 36).

Methodological articulations about the research process involving self-reflection are included in the chapters by Kate Viera and Steven Alvarez. In “Writing about Others Writing: Some Field Notes,” Viera reflects on her methodological education, learning to write about “others” and how she went about studying the writing practices of undocumented Portuguese-speaking immigrants. As she explains, Viera’s motivation for studying writing is its “liberatory potential” (49). But she worries that her writing separated her from the community she studied, one she hoped to belong to given their shared ethnicity. She points to the limitations of ethnographic research—research that runs the risk of objectifying those who find themselves in situations of unequal power positions in the research process. In an even more explicit attention to the self in ethnographic research, Steven Alvarez’s “Rhetorical Autoethnography: Delinking English Language Learning in a Family Oral History” enacts a grounded theory approach to oral histories he collected from his father and mother. The result is a critical autoethnography that focuses on the similarities and dissonances between his inability to learn Spanish and his parents’ individual experiences learning English as second-generation Mexican Americans in Bisbee, Arizona. His critical autoethnography illuminates how class, gender, and race relate to language performance. It is important to note that both of these chapters present approaches to self-reflection in relation to the subject of study, whether self or others.

Reflexivity can also be found in chapters that explicitly enact feminist methodologies. In her portion of the co-authored chapter, “La Cultura Nos Cura: Reclaiming Decolonial Epistemologies through Medicinal History and Quilting Method,” Sonia Arellano elaborates on the insightful potential of composing a quilt as data representation. The embodied process of quilting caused her to reflect on how she was personally affected by the stories she learned sewing a quilt composed of pieces of fabric left behind by migrants crossing the southern Arizona desert. Iris Ruiz, in her portion of the co-edited chapter, draws from Puerto Rican feminist Aurora Levins Morales’ exploration of historical recovery as medicinal for healing colonial wounds, thus differentiating her approach from other feminist rhetorical history projects that do not account for race or colonialism. In a similarly decolonial feminist approach, “Intersectional Reflexivity and Decolonial Rhetorics: From Palestine to Aztlán” offers a conversational reflection between Bernadette Marie Calafell and Haneen Shafeeq Ghabra. In their conversation, Calafell and Shafeeq Ghabra move away from an exclusively Eurocentric rhetoric, guided instead by women of color and transnational feminisms to explore the phenomenon of occupation and its impact on women’s bodies, especially those in the diaspora. Throughout the chapter, Calafell and Shafeeq Ghabra explore geopolitical similitudes between border walls affecting their ancestral homelands and how attending to those conditions can potentially afford alliance building. Not surprisingly, the explicitly feminist chapters are the ones that were written collaboratively, demonstrating the overall effort of the collection to bring together diverse decolonial visions. These collaborations exemplify the productive potential of reflexivity regarding heterogeneity in WRS.

In addition to including distinct identity positionalities, the contributors in this collection provide several pedagogical suggestions for how to enact a decolonial vision of the world. Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise contributes to the field’s repertoire of pedagogical strategies towards a socially just world. Of course, a decolonial approach that challenges the status quo cemented over years of imperialist development into unequal relations means that educators ought to encourage current and future generations to question, study, and take action regarding the most pressing issues of our time from a variety of perspectives. For example, Shyam Sharma argues for the benefits of teaching argumentation following the Nyãyasustra tradition from South Asia, proposing that adopting a non-western perspective can enhance a social justice orientation in the classroom.

As García and Baca suggest in their introduction, accounting for diverse subject positions has been a significant challenge to the normative standards and practices of academia’s white and Eurowestern epistemic and ontological composition. To address this issue, contributors consider elements of the local and the global in the specific geo- and body-politics they examine. In addition to the locations mentioned above, Fatima Zahrae Chrifi Alaoui nuances representations of Arab nations participating in the Arab Spring by studying Tunisian revolutionary graffiti. Both Chrifi Alaoui and Kevin Browne characterize vernacular rhetorics as a significant space of embodiment. Similar to Alvarez’ attention to personal records, Browne argues for the relevance of “ordinary contributions” like letters, notes, receipts, and photographs in studying Caribbean rhetoric (199). Identity formation, memory, and representation are therefore found, or, as Browne would put it, archived in both visual repertoires and seemingly mundane everyday life artifacts, regardless of people’s locations.

Reflecting on the applications of Browne’s articulation of Caribbean rhetorics, I find myself wondering about and even welcoming the impossibility of a singular Caribbean rhetoric. Provided that the editors are motivated by the contestation of modernity as a colonial imposition, I wonder how modernity is contested differently even between those of us who don’t identify with the traditional hegemonic epistemological repertoire of the US academy. For example, how does a Caribbean rhetoric from Spanish-speaking Antilles differ from the Anglophone or Francophone Caribbean? What about contestations of land and space within what Spanish colonizers dubbed Hispaniola and Haiti—where the descendants of those responsible for the first American liberation of enslaved peoples continue to struggle for survival (García-Peña)? What about the differential (and deferential) treatment of Dominican immigrants in Puerto Rico (Reyes-Santos)? These questions suggest that there needs to be further study and theorizing of a regional category—work that considers the cultural and human geographies enmeshed in such a pluralistic geo- and body-politic, which is, after all, what the collection advocates for.

Similar power dynamics and contestations occur in the contiguous United States, and a tension between decolonial projects from Indigenous scholars and other colonized peoples (including migrants, such as myself) cannot be easily dismissed. As a Puerto Rican woman, I cautiously claim a space in an academy that has historically resisted those who don’t fit a supposedly static standard of “excellence” and “merit” (refer to NCA’s contentious debate about Distinguished Scholars). Cautiously, because I both take heed of Tuck and Yang’s oft-cited article, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor” and listen to Indigenous scholars who find it unethical to claim indigeneity without tribal affiliation. While several chapters in the book reference Tuck and Yang, there are a few aspects from their argument that are unaccounted for. Namely, there could have been more explicit statements regarding the complicity and complexity of settler colonialism.

To be sure, there is a lot of work that is yet to be done, especially if we are to continue building alliances. It is reassuring that García and Baca anticipate such concerns. For them, there is an impetus for inquiry into decolonial options as the potential for “possibility, rather than certainty” (35), all while “understanding [that] one day we might need to decolonize those as well” (36). This work should motivate us, as Victor Villanueva suggests in the afterword, to strive for ways to “maintain our Self and our Other as a subjective collective … [as] we all share a memory, the memory of being Othered” (225). No matter how much complexity is involved in the process of studying and advocating for rhetorics elsewhere and otherwise, we must keep in mind that there is too much at stake not to do the work now and in the foreseeable future.

Bhambra, Gurminder K., et al., eds. Decolonising the University. Pluto P, 2018.

Flaherty, Colleen. “When White Scholars Pick Other White Scholars.” Inside Higher Ed, 13 June 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/06/13/communication-scholars-debate-how-fields-distinguished-scholars-should-be-picked.

García, Romeo, and Damián Baca, eds. Rhetorics Elsewhere and Otherwise: Contested Modernities, Decolonial Visions. National Council of Teachers of English, 2019.

García-Peña, Lorgia. The Borders of Dominicanidad: Race, Nation, and Archives of Contradiction. Duke UP, 2016.

Grande, Sandy. “Refusing the University.” Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education, edited by Mark Spooner and James McNinch, U of Regina P, 2018, pp. 168-192.

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Duke UP, 2003.

Powell, Malea. “2012 CCCC Chair's Address: Stories Take Place: A Performance in One Act.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 64, no. 2, 2012, pp. 383-406.

Reyes-Santos, Alaí. Our Caribbean Kin: Race and Nation in the Neoliberal Antilles. Rutgers UP, 2015.

Rodríguez, Clelia O. Decolonizing Academia: Poverty, Oppression and Pain. Fernwood Publishing, 2018.

Ruiz, Iris D., and Raúl Sánchez, eds. Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition Studies: New Latinx Keywords for Theory. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed., Zed, 2012.

Soto Vega, Karrieann. “Puerto Rico Weathers the Storm: Autogestión as a Coalitional Counter-Praxis of Survival.” feral feminisms, no. 9, 2019, https://feralfeminisms.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/5b-Soto-Vega.pdf.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1 2012, pp. 1-40.

Veracini, Lorenzo. “Introducing: Settler Colonial Studies.” Settler Colonial Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-12.

[i] Christina Cedillo provided permission for the post to be published in this essay. I am thankful to her for providing access to this source, and for the valuable feedback she offered in the production of this piece. Renowned Black feminist, Brittney Cooper’s tweet was recorded from her personal public twitter account.

[ii] Lorenzo Veracini succinctly describes the difference between colonialism (you, work for me) and settler colonialism (you, go away) as a necessary analytical distinction. I thank Dr. Kelsey John for sharing this work with me.

[iii] As massive protests call for abolition of the police, and the racial reckoning of histories of slavery as foundational to the U. S. nation state, the toppling of confederate statues has also prompted the removal of statues dedicated to Christopher Columbus. Signs in protests that read “ICE, you’re next” also provide an instantiation of a multifaceted approach to state violence and co-resistance.