Vanessa M. Cozza, Washington State University, Tri-Cities

(Published November 23, 2015)

[V]isual art has long been regarded as a rhetorical practice, concerned with narrative and with persuading and moving its audience.

Rampley’s “Visual Rhetoric”

Matthew Rampley notes that certain artistic and creative images tell stories, which can captivate and lead audiences to interpret and question their meaning. Street art serves as the best example of what Rampley suggests visual representations of reality aim to accomplish. Unlike graffiti writing or tagging,1 street art represents something – a person, object, or situation (Hill 25). Street artists attempt to use certain symbols that people will recognize, “speaking to them and for them” (Elansary). Take the politically charged mural that appears on a schoolhouse’s doors in São Paulo, Brazil (see Fig. 1). It depicts a hungry child holding a fork in one hand and a knife in the other hand. The child’s tearful eyes stare at a soccer ball positioned on top of a dinner plate. The image may make a viewer immediately question the Brazilian artist’s, Paulo Ito’s, intentions.

Fig. 1: World Cup Mural

While the mural’s artistic disposition may captivate most of its viewers, its message certainly becomes more meaningful to the country’s citizens. Ito’s mural addresses citizens’ reactions to Brazil’s hosting of the 2014 World Cup. Although poverty is a major problem, the World Cup took precedence over Brazil’s citizens, costing the country billions. Democracy Now! correspondent, Juan González, noted that “[m]any Brazilians have expressed fury over Brazil spending an estimated $11 billion to host the Cup while the country’s hospitals and schools remain woefully underfunded” (Goodman and González). Furthermore, Dave Zirin reported being teargased by police outside of Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro during a protest, which involved approximately 500 people (Goodman and González).

Street art, like Ito’s mural, appears in public spaces where people may normally not accept nor expect it. Through this visual means of communication, Ito and other similar artists have utilized a powerful medium that allows them to express their thoughts on social issues. While making specific references to community murals, LaWare explains that street art has “played an important role in creating an empowering identity” (2). Street artists can help foster public identity by revealing varying opinions on political matters that may spark concern in viewers and possibly unite groups of people. For instance, the function of street art in the Egyptian revolution – in which activists protested “poverty, unemployment, government corruption, and the rule of [the] president … who has been in power for three decades” (“Timeline”) – allowed artists to speak to and for the people. Describing it as the oldest form of social media, Meenakshi Ravi reports that street art became a powerful communicative tool in Egypt after President Hosni Mubarak banned Internet and cell phone use in 2011 (Ravi). In an interview with Ravi, blogger, Sobaya Morayef explains that street art became “symbolic for the uprising … [and] a direct reflection of people’s statements, of what they were trying to say … Street art spoke directly to the people.” Morayef adds, “What graffiti has done is raise awareness that there is another opinion” (Ravi). Street artist and author, RSH describes street art as “a communication platform for the disenfranchised. You have a group of people who have no other way of communicating. You have a message that’s being portrayed to everyone: ‘This person was killed. Stop this other person from doing these things.’ It directly affects the environment that it’s being placed in” (Ravi). Accessible to a wider audience, street art in certain situations has become necessary for “getting the word out” and making people realize the need for social change.

In this article, I argue that bringing this kind of artwork into the classroom can help students gain valuable insight into how powerful images can become symbols of social justice. David Darts argues that teachers need to consider how their pedagogies help students learn about social and political issues:

Teachers who are committed to examining social justice issues and fostering democratic principles through their teaching are obliged to consider how their pedagogical practices attend to the complex connections between culture and politics, and ought to evaluate how effectively their courses prepare their students to engage as thoughtful and informed citizens within the contemporary cultural sphere. (314)

What follows is my integration of street art into one of my advanced rhetoric courses, a 300-level course titled “Principles of Rhetoric.” By incorporating it into my lesson plans as a viable object of study, I witnessed its potential for increasing students’ rhetorical knowledge and engagement in global matters. It became a visual handbook, similar to Aristotle’s Art of Rhetoric, which Kenneth Burke described as a “handbook on a manly art of self-defense” (52) – a handbook that armed his audience with tactics to argue successfully. Ultimately, street art can expose students to rhetorical tactics and strategies and, at the same time, teach them about politics and history.

Why public street art?

While rhetorical studies scholarship and pedagogy pays attention to different forms of visual communication within multiple contexts, it seems to privilege certain creative media. Most visual media valued as viable objects of study include digital spaces, famous paintings, iconic photographs, images in advertisements, magazines, television commercials and news, documentaries, billboards, “architecture, interior design, [and] dress” (Foss 141). For example, research essays that appear in edited collections and online peer-reviewed journals usually examine how people compose in certain digital spaces, such as in wiki, blogs, or social networking sites, or analyze how visually-engaging and interactive software affects composing, learning, and teaching, such as the use of the presentation software, Prezi. Additionally, course readings and texts that introduce students to visual rhetoric demonstrate careful selection of the most valued pieces of art or images that appeal to and reflect society’s privileged groups or the dominant culture. Similar texts for a majority of students depict familiar media, pieces of art and images that they may frequently encounter in museums, theatres, in other texts, on television, and on the Internet. As Kristin Lee Moss explains, “[H]istorically the dominant culture has assumed and promoted an elite White version of what was considered good art” (373). What the majority deems valuable or labels as “popular culture” becomes foreign to underrepresented populations who lack access to certain cultural privileges. The careful selection of material stresses the importance of legality as it steers clear from presenting noncommissioned or what some may consider as illegal artwork. Furthermore, Sonja K. Foss observes that “[t]he study of visual imagery from a rhetorical perspective also has grown with the emerging recognition that visual images provide access to a range of human experience not always available through the study of discourse” (143). Street art, rarely thought about as an object of study, offers a different space for inquiry. My focus in this section is to show just that, positioning street art – art that aims to “[interact] with the audience on the street and the people, the masses” (Lewisohn 15) – as a viable object of study and communicative tool manifested by analyzing graffiti, photographic images, and wheat paste murals that are, what Charles A. Hill describes, “representational images” (25).

Foss explains what constitutes a representational image worthy of rhetorical study; she notes three characteristics: “The image must be symbolic, involve human intervention, and be presented to an audience for the purpose of communicating with that audience” (Foss 144). In other words, the visual object must convey an idea or concept, “[require] human action either in the process of creation or in the process of interpretation” (Foss 144), and attract and engage viewers. Public street art encompasses all of these characteristics. More importantly, Darren Newbury stresses that this type of work – studying visual images in general – requires careful consideration and deserves the same attention that we give “to other materials with which we work. It insists that we think carefully about what images are and how they may be used to communicate ideas and make arguments” (662). Newbury’s assertion seems valid, especially considering that visual scholars have proposed different methods for analyzing images (654). Specifically, he explains that scholars focus on illustration, analysis, and argument (Newbury 654). My intentions in this piece are not to propose a specific analytical method; rather my focus is to show what students can gain from studying the visual rhetoric of street art. As Foss points out, visual rhetoric “focus[es] on a rhetorical response to an image rather than an aesthetic one” (145). This rhetorical approach includes analysis, “where the image itself is the focus of attention, the object of study” (Newbury 654), and where we’re concerned with “the nature of the image as it presents itself to the viewer, an acknowledgement that what we are looking at is an image, not the thing itself” (654). In other words, we keep in mind the visual elements that make up the image, realizing that they differ from the conventions of discursive practices (Langer 75), and we look for how the image is “explicitly designed to convey an argument” (Newbury 654). Margaret LaWare points out that communities can use visual images to make arguments (2), and when analyzing visual arguments, she stresses that it is important to examine them in their respective geographical and cultural contexts (3). For these reasons, I had students identify what kind of arguments the street artists were making, and had them explore how they were making those arguments within the context in which the artwork appeared.

Identifying the Argument within Context

I incorporated street art into an advanced rhetoric course, where students examined the various components involved in persuasion. Specifically, the course’s central theme centered on rhetoric in public work; in other words, students studied how rhetoric functioned in the public arena – ranging from persuading people to hold or reject certain values to convincing them of the need for social change. In doing so, students were asked to read, look at, and listen to many different kinds of public discourse and “texts,” including speeches, architecture and design, photographs, and street art. While exploring these artifacts, students learned about several strategies (see Appendix A) for rhetorical analysis and critique, applied those strategies to a variety of texts, and employed those strategies in the texts that they produced. Ultimately, the course aimed to show how rhetoric and writing supports local-global civic engagement. I designed two specific assignments geared toward studying the rhetoric of street art. The first assignment, which I discuss in this section, asked students to examine two street artists’ works, the French artist, JR, and the Italian artist, Blu (see Appendix B).

John Duffy defines rhetoric as “the ways that institutions, groups, or individuals use language and other symbols for the purpose of shaping conceptions of reality” (42). JR and Blu’s projects illustrate Duffy’s definition: JR’s photography and Blu’s murals comprise the language or symbols used to communicate, and the streets have become their canvas to address political and social issues. Duffy adds, “To see literacy development as rhetorical is to consider the influence of rhetorics on what writers choose to say, the audience they imagine in saying it, the genres in which they elect to write, and the words and phrases they use to communicate their messages” (43). Likewise, visual rhetoric influences the artist’s literacy practices. First, they have to make rhetorical decisions about the message, the location where the target audience would appear, the medium, and the image(s) created to convey the message. Then, they have to execute those decisions by writing, sculpting, painting, pasting, and/or drawing. Furthermore, size and location greatly contribute to a street artist’s work.

JR in Washington, D.C.

JR takes close-up, photographic images of human faces and displays gigantic portraits of them onto “the sides of buildings, bridges, trains, buses, and rooftops” (“JR: Street Artist”). His work attracts and distracts a wide audience, particularly people who don’t have the opportunity to visit art museums. More importantly, the content of JR’s photographs call attention to individuals who often are discriminated, ignored, or oppressed. While presenting his work at the 2011 TED conference, he asked people to participate in his global art project by taking their own photos and sending them to him (“JR’s TED Prize wish”). By involving the public, JR’s artwork serves as a powerful, rhetorical weapon, which can arm underrepresented groups with the necessary tools to make their voices heard. JR’s goal is to not only incorporate art into places and spaces where it might normally not be accepted nor expected, but also to encourage people to observe and wonder what is going on. In other words, he wants communities to ponder and question the artwork’s message, which has become a similar outcome with Ito’s World Cup mural whether he intended it or not.

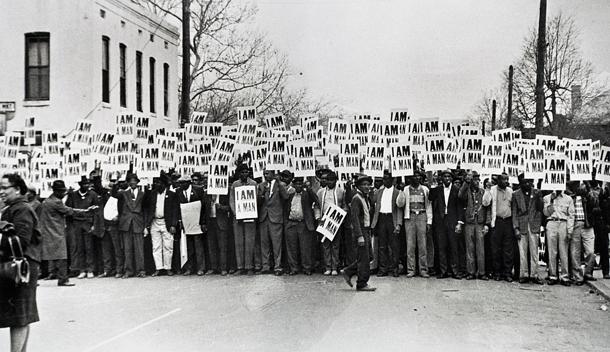

In some cases, JR’s photography can help viewers remember significant historical figures or events. I asked my students to compare one of JR’s pieces, the I Am a Man mural (see Fig. 2), and one of Ernest Withers’ photographs of “workers assemble[d] in front of Clayton Temple for a solidarity march [in] Memphis, Tennessee, 1968” (Landry and DeVito) (see Fig. 3). They had to identify the rhetorical strategies that appear in the mural and photograph, and explain their effectiveness by drawing from specific examples in the images, all while considering the context of each image. The comparison led students to further explore the 1968 sanitation strike in Memphis, giving them the opportunity to expand their historical knowledge.

Completed in October 2012, JR’s installation shows a crowd of African American men holding white, picket signs with the phrase, “I Am A Man” painted or stenciled in bold, black letters. The photos pasted on the side of an abandoned building (Judkis, “French artist”) replicate Withers’ photograph, which captures a significant moment during the civil rights movement. As Taylor Rogers explains, the sanitation workers demanded better treatment, including “decent working conditions, and a decent salary” (qtd. in Green 465). Some students recognized the photograph, having studied the civil rights era, while others expressed interest in learning more about it.

Fig. 2: JR, I Am a Man

Fig. 3: Withers, I Am A Man

JR’s mural not only reminded students of an important part of U.S. history, but it also made them realize the timeliness of the message. As J. Anthony Blair points out, “[t]he narratives we formulate for ourselves from visual images can easily shape our attitudes” (43). That is, visual images, like JR’s installation, can tell stories that we interpret and allow to construct our worldview. The “I Am A Man” picket signs symbolized freedom and human rights for the sanitation workers in 1968. Given today’s political climate, from the George Zimmerman trial in Summer 2013 to Michael Brown and Eric Garner’s shootings the following year as well as Sandra Bland’s death earlier this year, JR’s installation continues the call for freedom and human rights, and similar interpretations of the original photograph and mural have influenced others to send a similar message. In an interview with Maria Judkis, JR explains, “This says it all, ‘I am a man’ … They created such a strong and powerful image that still resonates today, but in another context. Still people say, ‘I am a man,’ but they care less about the color [of their skin]. It’s ‘we are humans, we are here, we want to exist.’ And I like that, I think it’s pretty powerful” (Judkis). Likewise, the “I Am A Man” signs have reappeared in response to Michael Brown’s shooting and have taken many different forms (see Fig. 4 and 5), reaffirming JR’s comment that the Withers’ photograph is meaningful today.

Fig. 4: Hastings/AP/Corbis, Protesters in Ferguson

Fig. 5: Maury, Protester in sweatshirt

The installation’s location also contributes to JR’s message; located in Washington D.C. at 14th T Street NW, JR notes that it “[speaks] to the history of the neighborhood after the riots that followed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and to the state of American society now” (Judkis).

Blu in Buenos Aires

Similar to JR, Blu’s controversial artwork not only appears in public spaces where people usually pass, but also it occupies a substantial area of tall and/or wide buildings; the size of his work makes it unavoidable for audiences to notice. Food and travel editor, Elisa della Barba, describes Blu as an internationally-known artist who takes risks and has a unique style (della Barba). Blu’s socially- and politically-driven artwork “portray[s] human figures in a sarcastic and dramatic way” (della Barba). He has also collaborated with other artists, such as JR (della Barba). I asked my students to examine two of Blu’s murals, Follow the Leader (see Fig. 6) and Blu’s BBQ (see Fig. 7). Again, students had to identify the rhetorical strategies used in the murals, explain their effectiveness, and draw from specific examples within the murals to support their claims. Blu’s murals prompted my students to ask questions about Argentine history and politics, which helped develop their understanding of the mural’s context and increase their global knowledge.

Completed in November 2011, the first mural shows a crowd of people with ribbons wrapped around their ears, eyes, and mouths. The ribbons consist of two blue strips alongside of one white strip in the middle, resembling the Argentine flag. In this case, the ribbon’s design of the Argentine flag is missing an image of a bright, yellow sun, which usually appears in the middle. A silhouette of a person, a man in a black suit and tie, appears in the far-right corner, overlooking the crowd. The mysterious man wears the Argentine flag as a sash around his body. Although students didn’t have extensive background on Argentina, they surmised that the mural critiqued the country’s politics. The positioning of the ribbons seems to represent the maxim, “See no evil. Hear no evil. Speak no evil.” The crowd’s inability to see, hear, and speak prevents them from observing, listening, questioning or challenging what is happening around them. Thus, the silenced crowd blindly follows the leader, the man in the black suit and tie. Blu’s Follow the Leader may highlight the “military dictatorship that controlled [the country] in the 1970s and 1980s” (Kaminsky 158). More specifically, Amy K. Kaminsky describes the military coup’s efforts to violently silence public opposition; she notes:

The Dirty War, waged by Argentine military junta against dissidents and possible dissidents, including students, trade unionists, psychiatrists, writers, and artists, as well as against an underground guerrilla movement, suppressed just about every shred of dissent Argentina’s civil society could muster, usually by violence or the threat of violence. (241)

Some people regard Argentine politics as having a similar effect today on the country’s citizens. That is, the people blindly follow authority without inquiry or protest. Others don’t see this as being the case, arguing that Argentina’s economy and leadership have improved. BA Street Art reported that someone had defaced Blu’s mural with the letter “Y” and a question mark in red graffiti. The letter “Y” in Spanish means “and,” which possibly indicates that the graffiti writer questions the mural’s message and significance, as if asking, “And, what?” BA Street Art also noted that an image of the mural on Facebook had “provoked more than 150 comments … with both praise and insults in equal measure” (BA Street Art). One person commented: “This is exactly what happens in Argentina, would you like it so that we don’t see anything and live in ignorance, it is like that. The graffiti is very good” (BA Street Art). While another remarked: “Blind patriots and fools. Argentina isn’t like that” (BA Street Art).

Fig. 6: Blu, Follow the Leader

In the same year, Blu created another mural, Blu’s BBQ (Buenos Aires). The second mural shows a pile of Argentine currency, pesos, burning underneath massive flames. Above the flames appears a parrilla or grill with six human figures, roasting like asado or Argentine barbeque (Buenos Aires). Another piece that seems to critique Argentine politics, this mural represents the fall of a corrupted government and its leaders. Students reacted more to Blu’s BBQ than they had to his Follow the Leader mural, immediately questioning the artist’s intentions. Some students expressed shock and admitted mainly being drawn to the human figures roasting above the flames.

Fig. 7: Blu, Blu’s BBQ

As a class, we inferred that the mural depicted a significant, political event or perhaps a series of historical occurrences. Specifically, I had explained that the mural possibly depicts Argentina’s major economic meltdown, which occurred “throughout the end of 2001 and the beginning of 2002” (Schamis 81). Hector E. Schamis explains that a weak government and riots across the country led the “first Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo, then the rest of the cabinet, and finally [President Fernando de la Rúa to] all [resign]” in late December (81). This explanation of Blu’s mural seems fitting as Argentina’s unstable, economic trajectory that led to the crisis in late 2001 reflects the irresponsibility of its leaders. The visual representations in Blu’s murals motivated students to engage not only with the rhetoric, but also to further investigate the murals’ historical and political significance. The students’ analyses and discussions of Blu and JR’s murals helped them to create their own artwork for their final project in the course.

Becoming the Artist

Drawing from what the students learned in the group activity, they applied some of the rhetorical strategies and concepts to their own art and considered historical, political, and social contexts. Darts makes a valid point when he explains that “[b]y calling attention to the social, political, cultural, and religious mechanisms and restrictions that inform our actions and temper our beliefs, artists are able to expose us to ourselves, to each other, and to the world we are attempting to cultivate together” (319). Street art has the ability not only to turn heads, but also to make viewers think about certain issues that directly impact their lives and the people around them. For the second assignment, I had students create their own artwork in an attempt to make it accomplish what Darts notes as the artist’s ability (see Appendix C). Darts also highlights the significance of art educators “introducing the work of socially engaged artists into their classrooms” (319). In addition to exposing students to social and political issues, teachers of rhetoric can use public street art to show creative ways of thinking and communicating. For this reason, students were given four options in which they had to choose one to complete for their final project in the course. Option #2, the photographic collage, and Option #3, the mural, represent the kind of public street art detailed in this article. For the photographic collage, the student had to take photos and make a collage that reflected social change or represented the need for action. For the mural, the student had to create a mural on poster board that conveyed a message about social injustice. Two students in particular created projects similar to JR and Blu’s pieces. The first student, Megan, selected Option #2, where she took photographs that represented Native American history in Washington State’s Tri-Cities area (see Fig. 8). The second student, Ken, selected Option #3, where he created a mural representing his version of the three wise men (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 8: Megan, Photographic Series

Megan’s rhetorical strategies included making decisions about the medium, the message itself, the images to convey the message, the photographic collage’s size, and its location. Megan’s project shows miniature figurines of Native Americans appearing in “both natural and unnatural” environments (“Final Project Reflective Essay” 1). In her reflective piece, Megan notes wanting to address “the misrepresentation of Native American people by popular media” (1) with this project. Furthermore, her project takes a similar approach to JR’s I Am a Man; Megan’s photographic series aims to remind viewers of “the forgotten people who once dominated ... the Columbia Basin” area (1), an important part of U.S. history. The size of her figurines and their placement contribute to her message as an artist and as a rhetorician. Megan explains that her use of the figurines “[depict] a more commercial looking Native American” and their placement “[depict] both natural and unnatural surroundings” (“Final Reflective Essay” 2). Megan also offers an explanation and example in her reflective piece. She notes, “[A] figure hides alongside the trunk of a tree, placed as though he has been isolated” in one of the photographs; “[D]warfed by [its] surroundings,” the positioning of the figurine “bring[s] attention and awareness ... to [the] misrepresentation and belittling” of Native Americans (“Final Reflective Essay” 2). Additionally, just as JR decides where to place his installations, Megan explains where she would place her project. She details wanting to “display [her] photographs ... in public parks, museums and perhaps even local galleries or event spaces;” she adds, a space and place where “someone, who might be unfamiliar with the history of the Native Americans in [the Tri-Cities] area, would come across them” (“Final Reflective Essay” 2). Similar to JR’s photography, Megan’s project calls attention to an oppressed group, providing them a voice and reminding viewers of their tragic history. Her project also demonstrates her knowledge of the strategies necessary to engage viewers and spread awareness of the issue, just as the students became engaged during the group activity.

Fig. 9: Ken, The III Wisemen

Ken’s project achieves similar strategies, including decisions concerning the medium, the message and how he will convey it, the mural’s size, and its location. His project shows three well-known, iconic figures: Bruce Lee, Bob Marley, and Mahatma Ghandi. The phrases, “Be Water,” “One Love,” and “Complete Harmony” hover over each figure; each phrase is a quote by the famous person below it. Underneath of them, the phrase “The III Wisemen” appears. In his reflective piece, Ken explains that Lee, Marley, and Ghandi represent a contemporary depiction of the three wise men or the three kings in the Bible (“Reflective Essay: The III Wisemen” 1). He adds that his “version of the religious reference is three people [who he] admire[s] because of their philosophies of adaptability, consciousness, and unity” (1). Similar to JR’s iconic photography of I Am a Man and Blu’s artwork, Ken’s project reminds viewers of significant contemporary figures and worthy virtues to live by. In addition, the size and placement of Ken’s project contribute to his message as well (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Ken, Location

Ken highlights his decision to place his piece “on the strip of Las Vegas” to “reach a wide audience,” including local citizens and national/international travelers (“Reflective Essay: The III Wisemen” 2). He also points out that viewers can still decipher the message even if they are unfamiliar with the figures' quotes (“Reflective Essay: The III Wisemen” 2). The rhetorical strategies that Ken uses in his project resemble Blu and JR’s decisions to place their street art in areas where they can capture the attention of a large group and to create gigantic pieces that become visible for everyone to notice.

Incorporating Street Art into the Classroom

Megan and Ken’s final projects reflected their understanding of how rhetoric can function in public spaces, and in particular, how it can function in street art. However, there were limitations that I address in this concluding section and that I advise other teachers take into consideration if they decide to incorporate street art into the classroom.

I’m aware that my approach limited the opportunity for students to become active agents outside of the classroom. The assignment didn’t require them to display their visual projects in a public space, although I did encourage them to do so. Instead, I assigned my students to write a reflective essay and present their work to the class, while explaining specifically where they’d place their visual projects. Ideally, students should be given the chance to “get the word out” by making their work available to a nonacademic audience. I realize that every institutional context differs, but if possible, teachers can make it a requirement for students to display their art in some kind of public space. Students can place their art in local coffee shops, libraries, grocery stores, and other public venues, or they can share their art at an undergraduate research symposium. Either way it would allow them to expand their audience and perhaps further investigate the social effects of the artwork.

The lessons and assignments focused more on the artist’s intentions and rhetorical strategies, and they didn’t fully consider the social effects of the street art. In discussing Egypt’s revolutionary street art, Hannah Elansary highlights a two-way communicative relationship between artists and their viewers. She explains “a process of art production,” noting that for artists, “street art served as a tool by which citizens could (re)claim agency, assert identity, and create their own historical narratives” (Elansary). On the other hand, “reception or effect” of the street art has to do with viewers’ reactions to it (Elansary). After interviewing 57 people about street art, Elansary heard a number of varying perspectives: some didn’t respond well to the street art, not viewing the artists as “speaking for or to them,” and others believing that the artists are “speaking at them” reinforced the ideas that they were “reclaiming public space, reclaiming agency, and building community - implying that the artists created these images for the Egyptian people in hopes of instilling them with these sentiments of community, agency, and ownership of the street” (Elansary). Elansary’s distinction between the “process of art production” and “reception or effect” reveals the importance of understanding both the artist’s message and viewers’ reactions to it. I advise that teachers design lessons and assignments that give students the opportunity to investigate how street art influences its viewers. For instance, teachers can ask students to research public reactions to a particular mural by reading comments posted on Facebook or Twitter.

Aside from encouraging public engagement and investigating the social effects of street art, it’s important to make the street art a unit among other things and to offer options that can meet all students’ abilities. As the final project’s assignment sheet shows, the course focused on other mediums, such as speech and architecture (see Appendix C). By giving students the option to complete one of the four assignments for the final project – a speech, a photographic collage, a mural, an architectural piece – they could choose based on their abilities and interests. Whatever option the students chose, they had to apply the rhetorical strategies and concepts that they learned throughout the semester. Street art as an object of rhetorical study helped further students’ understanding of how rhetoric functions in public spaces; it allowed them to gain insight into what kind of arguments street artists make and in what historical, social, or political contexts they make them. More importantly, it gave students the chance to expand their attitudes toward art and its place in the world.

Appendix A

Rhetorical Strategies and Concepts

Before students completed the first assignment, I introduced them to several rhetorical strategies and concepts. For the purpose of the course and its context, I focused on the following terms and concepts for looking at and analyzing street art:

1. Identifying the Rhetorical Situation

a. Subject – What is it about?

b. Context – What happened or what is going on?

c. Purpose – What do you think is the artist’s intent?

d. Audience – Who do you think is the target audience?

2. Recognizing Rhetorical Principles

a. Aristotle’s Modes of Proof2

i. Ethos – How does the artist establish credibility with the viewer?

ii. Logos – How does the artist appeal to the viewer’s intellect?

iii. Pathos – How does the artist appeal to the viewer’s emotions?

b. Canons of Rhetoric

i. Invention – What did the artist consider in preparing or conceiving and developing the piece?

ii. Arrangement – How is the artist’s piece arranged, ordered, or structured?

iii. Delivery – What is the medium used?

iv. Style – What descriptive language (text/words/phrases) is used?

c. Visual Rhetoric3

i. Representation/symbolism – Do you notice any images that stand for something else, that represent a common theme or idea, that resemble a condition/state (iconic), or that relies on connections (indexically)?

ii. Location and space – Does where the piece appear have any significance? Does its location (where it is placed) and space (size, placement, and surroundings) contribute to the artist’s overall message?

iii. Denotative/literal description – What do you see? What is there?

iv. Connotative/cultural or historic context – What does it mean? What is the message?

v. Page layout

1. Consistency – Is the artist consistent in what he/she uses?

2. Proportion/balance – Is equal time devoted to parts of the piece? Is there too much white space, too much of one color, too much text, etc.?

3. Unity/wholeness – Is the artist’s piece unified or fragmented?

4. Textual/physical presentation – What font(s) did the artist use? What typeface(s) (size and style) did the artist use? What specific typestyle(s) (plain, bold, underline, italic, etc.) did the artist use?

vi. Eye movement/focus – Where do you begin looking at the image? Where do you stop looking at the image? In what direction does your eye move?

vii. Lighting – Is the image dark? Is it bright?

viii. Background/foreground (focus) – Do you focus on the background or foreground? Is either one blurred, shaded, or more focused?

ix. Details – What do you see? Do you notice anything about body positioning, facial expressions, interactions with others, placement, location, space, etc.?

x. Gaze – Where are people looking? Are they looking up or down? Are they looking to the side?

xi. Frame/cropping – Can you tell if the image has been cropped? Is there a lot of space? Is there minimal space? Is there a border or frame around it?

3. Visual Arguments

a. Narrative – Does the visual’s content tell a story? Does it rely only on the image(s) or does it rely on printed text as well?

b. Kairos – Has the artist considered timeliness? Does the piece have relevance and significance given the time and context?

c. Source – Who is the artist?

d. Enthymeme – What is the argument? Is there a gap that needs to be filled by the audience? If so, what is it?

Appendix B

Group Activity

To strengthen students’ understanding of the rhetorical strategies and concepts listed in Appendix A, I asked them to work together in groups and answer the following questions based on JR and Blu’s street art.

JR in Washington, D.C.

1. What are you going to prove? Ernest Withers’ photograph and JR’s mural demonstrate effective (Point #1)_________________and (Point #2)______________________.

2. Topic sentence: What is Point #1?

3. Who cares? Why is Point #1 important?

4. Examples: Provide two specific examples, one from the first image and one from the second image, which demonstrate Point #1.

5. Connection: Why do the two examples that you offered prove Point #1 and the thesis statement overall?

6. Transition: How does Point #1 relate to Point #2?

7. Topic sentence: What is Point #2?

8. Who cares? Why is Point #2 important?

9. Examples: Provide two specific examples, one from the first image and one from the second image, which demonstrate Point #2.

10. Connection: Why do the two examples that you offered prove Point #2 and the thesis statement overall?

Blu in Buenos Aires

1. What are you going to prove? Blu’s murals in Buenos Aires, Argentina demonstrate effective (Point #1)____________ and (Point #2)_________________.

2. Topic sentence: What is Point #1?

3. Who cares? Why is Point #1 important?

4. Examples: Provide two specific examples, one from the first image and one from the second image, which demonstrate Point #1.

5. Connection: Why do the two examples that you offered prove Point #1 and the thesis statement overall?

6. Transition: How does Point #1 relate to Point #2?

7. Topic sentence: What is Point #2?

8. Who cares? Why is Point #2 important?

9. Examples: Provide two specific examples, one from the first image and one from the second image, which demonstrate Point #2.

10. Connection: Why do the two examples that you offered prove Point #2 and the thesis statement overall?

Appendix C

Final Project

Instructions

This final project involves three components.

1) First, you have four options for this final project. Choose to create one of the following:

- A speech. Write and recite an original speech that you would give in a public venue about a local or national problem that matters to you.

- A photographic collage. Take photos and make a collage that reflects social change or represents the need for action.

- A mural. Create a graffiti mural on poster board that sends a message about social injustice.

- An architectural piece. Design a blueprint or build an architectural piece that captures social progress and addresses environmental problems.

2) Second, you will sign up to present your project on one of the following days:

- Friday, November 30th

- Monday, December 3rd

- Wednesday, December 5th

- Friday, December 7th

Your presentation should be no more than 10 minutes. Depending on which option you choose, you will present the following:

- A speech. Briefly provide the context for your speech, describing where you would give it, for what purpose and intended audience. Recite it. Then, leave at least 1-2 minutes to discuss your creative thought process including the rhetorical techniques you considered and used.

- A photographic collage. Briefly discuss your reason(s) for choosing this option, its purpose, intended audience, and your creative thought process including the rhetorical techniques considered and used.

- A mural. Briefly discuss your reason(s) for choosing this option, where it would appear, its purpose, intended audience, and your creative thought process including the rhetorical techniques considered and used.

- An architectural piece. Briefly discuss your reason(s) for choosing this option, where it would appear, its purpose, intended audience, and your creative thought process including the rhetorical techniques considered and used.

3) Third, you will write a one-page reflective essay that addresses the presentation points noted above for the specific option that you choose. For the speech option, please submit a typed copy of the speech that you delivered in class along with your reflective essay.

- 1. Cedar Lewisohn distinguishes between graffiti writing and street art: “‘Graffiti writing,’ which is separate from graffiti, is the movement most closely associated with hip hop culture (though it pre-dates it), whose central concern is the ‘tag’ or signature of the author” (15). Graffiti writing isn’t meant for the public; rather, it is geared toward a specific group of people

- 2. I used Sharon Crowley and Debra Hawhee’s Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students to teach Aristotle’s modes of proof, the canons of rhetoric, and some of the concepts in visual arguments

- 3. To teach students about visual rhetoric, I used Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright’s Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, Duke University’s Writing Studio handout titled “Visual Rhetoric/Visual Literacy: Writing about Photography,” and Purdue’s Online Writing Lab (OWL) handout titled, “Visual Rhetoric: Overview.”

Blair, J. Anthony. “The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments.” Defining Visual Rhetorics. Eds. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004. 41-61. Print.

Blu. Blu’s BBQ. Buenos Aires. buenosairesstreetart.com. Web. 28 Aug. 2013.

---. Follow the Leader. Buenos Aires. buenosairesstreetart.com. Web. 28 Aug. 2013.

BA Street Art. “Controversial mural by Blu in Buenos Aires vandalized with graffiti.” BA Street Art, 2012. Web. 17 June 2013.

Buenos Aires Street Art and Graffiti. BA Street Art, 2013. Web. 17 June 2013.

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: U of California P, 1969. Print.

Crowley, Sharon, and Debra Hawhee. Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students. 5th ed. Boston: Pearson, 2012. Print.

Darts, David. “Visual Culture Jam: Art, Pedagogy, and Creative Resistance.” Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research. 45.4 (2004): 313-327. Print.

della Barba, Elisa. “Blu: why street art matters.” Swide. Nov. 2012. Web. 28 Aug. 2013.

Duffy, John. “Other Gods and Countries: The Rhetorics of Literacy.” Towards a Rhetoric of Everyday Life: New Directions in Research on Writing, Text, and Discourse. Eds. Martin Nystrand and John Duffy. Madison: U of Wisconsin, 2003. 38-57. Print.

Duke University Writing Studio. “Visual Rhetoric/Visual Literacy: Writing About Photography.” Duke University, 29 Apr. 2010. Web. 17 June 2013.

Foss, Sonja K. “Theory of Visual Rhetoric.” Handbook of Visual Communication: Theory, Methods, and Media. Eds. Ken Smith, Sandra Moriarty, Gretchen Barbatsis, and Keith Kenney. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005. 141-152. Print.

Goodman, Amy, and Juan González. “Dave Zirin on the World Cup You Won't See on TV: Protests, Tear Gas, and Displaced Favela Residents.” Democracy Now! democracynow.org, 16 June 2014. Web. 2 July 2014.

Green, Laurie B. “Race, Gender, and Labor in 1960s Memphis: ‘I am a Man’ and the Meaning of Freedom.” Journal of Urban History 30.3 (2004): 465-489. juh.sagepub.com. Web. 2 Sep. 2013.

Hastings/AP/Corbis, Sid. Protesters in Ferguson. Photograph. New York Magazine. 2014. Web. 21 May 2015.

Hill, Charles A. “The Psychology of Rhetorical Images.” Defining Visual Rhetorics. Eds. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004. 25-40. Print.

Ito, Paulo. World Cup Mural. Sãn Paulo. soccerly.com. Web. 17 July 2014.

JR – Artist. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 June 2013.

---. I Am a Man. Washington D.C. washingtonpost.com. Web. 2 Sep. 2013.

“JR: Street Artist.” TED: Ideas Worth Spreading. N.d. Web. 17 June 2013.

“JR’s TED Prize wish: Use art to turn the world inside out.” TED: Ideas Worth Spreading. Mar. 2011. Web. 17 June 2013.

Judkis, Maura. “French artist JR covers D.C. building with iconic image of civil rights era.” The Washington Post. Oct. 2012 Web. 2 Sep. 2013.

---. “Street artist JR to install mural on 14th Street.” The Washington Post. Sep. 2012 Web. 2 Sep. 2013.

Kaminsky, Amy K. Argentina: Stories for a Nation. Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 2008. Print.

Ken. Location. 2012. Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland.

---. "Reflective Essay: The III Wisemen." Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland. 2012.

---. The III Wisemen. 2012. Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland.

Landry, Jason, and Anne DeVito. “Ernest Withers.” Panopticon Gallery. Panopticon Gallery, n.d. Web. 17 June 2013.

Langer, Susanne K. Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. New York City: The New American Library, 1954. Print.

LaWare, Margaret R. “Encountering Visions of Aztlán: Arguments for Ethnic Pride, Community Activism and Cultural Revitalization in Chicano Murals.” Visual Rhetoric: A Reader in Communication and American Culture. Lester C. Olson, Cara A. Finnegan, and Diane S. Hope, Eds. Los Angeles: Sage, 2008. 227-239. Print,

Lewisohn, Cedar. Street Art: The Graffiti Revolution. Abrams, NY: Tate Publishing, 2008. Print.

Maury, Tannen. A protester in a sweatshirt that reads ‘I Am Mike Brown’ walks into walks into the memorial site for Michael Brown. 2014. Photograph. USA Today. Web. 21 May 2015.

Megan. "Final Project Reflective Essay." Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland. 2012.

---. Photographic Series. 2012. Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland.

Moss, Kristin Lee. “Cultural Representation in Philadelphia Murals: Images of Resistance and Sights of Identity Negotiation.” Western Journal of Communication. 74.4 (2010): 372-395. EBSCOhost. Web. 4 July 2013.

Newbury, Darren. “Making Arguments with Images: Visual Scholarship and Academic Publishing.” The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods. London: SAGE, 2011. 651-664. Print.

Rampley, Matthew. “Visual Rhetoric.” Exploring Visual Culture: Definitions, Concepts, and Contexts. Ed. Matthew Rampley. Edinburgh, SCT: Edinburgh UP, 2005. 133-148. Print.

Ravi, Meenakshi. “The power of street art.” Aljazeera, 2012. Web. 8 June 2015.

Schamis, Hector E. “Argentina: Crisis and Democratic Consolidation.” Journal of Democracy. 13.2 (2002): 81-94. Project Muse. Web. 28 Aug. 2013.

Stolley, Karl, Mark Pepper, Allen Brizee, and Elizabeth Angeli. “Visual Rhetoric: Overview.” Purdue OWL, 2012. Web. 7 Oct. 2012.

Sturken, Marita and Lisa Cartwright. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

“Timeline: Egypt’s Revolution.” Aljazeera, 2011. Web. 8 June 2015.

Withers, Ernest. I Am A Man. Memphis. panopticongallery.com. Web. 28 Aug. 2013.